[Stephen J. Thorne]

Based in Yellowknife, the retired warrant officer finds no greater satisfaction than uncovering unmarked or incomplete graves, tracking down names, interviewing families, Rangers and Elders, and exploring service histories.

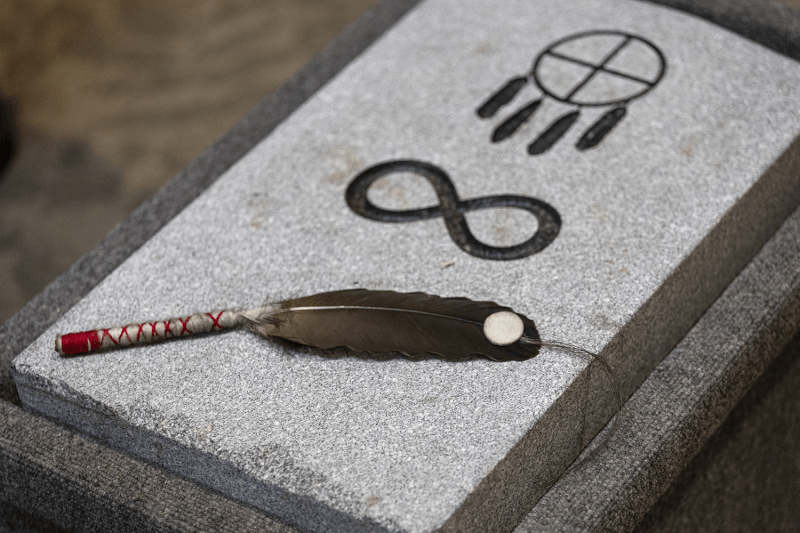

The payoff comes a year or more down the road when families, colleagues and communities gather to pay their respects as a familiar grey granite headstone—usually bearing appropriate Indigenous iconography—is placed on a plot, finally granting an oft-long-departed veteran their due, in perpetuity.

“It is challenging,” acknowledged Power, who served 32 years in the army and is among the volunteer researchers featured in a 19-minute film The Indigenous Veterans Initiative—Finding Unmarked Graves, produced by the program creator and chief sponsor, the Last Post Fund. “It is very personally satisfying.

“I am a member of The Royal Canadian Regiment and our regimental philosophy is never pass a fault. I don’t need thanks or praise or whatever. It’s the right thing to do and the philosophy of my regiment holds true in correcting this fault.”

[Stephen J. Thorne]

“I saw that list and I thought a lot of those persons who served must be in unmarked graves.”

The Last Post Fund introduced the Indigenous Veterans Initiative in 2019 as part of its overall mission to ensure that all veterans have a dignified funeral and burial, along with a military gravestone.

The fund’s executive director Edouard Pahud conceived the idea after Quebec amateur historian Yann Castelnot compiled a list of 250,000 Indigenous personnel who had served with American or Canadian forces since Europeans first arrived on the continent in the 17th century.

“I saw that list and I thought a lot of those persons who served must be in unmarked graves,” said Pahud. “So, I called him up and asked him if he would share the Canadian component of the list with us. He agreed.”

And the fund’s Indigenous research began.

The Indigenous initiative has its special challenges: a disproportionate number of the country’s 12,000-plus Indigenous veterans are believed to lie in unmarked graves, partly due to the economic plight their families faced. Yet just a small number of Indigenous communities are collaborating with the project.

“Some communities know about our program, some don’t,” said its co-ordinator Maria Trujillo. “I think it’s more due to the fact that Indigenous communities might not have had access to know about us.

“The word just wasn’t getting out to them that we existed as an organization and part of this initiative is getting the word out there that we exist and this is available.”

Canadian Rangers observe the National Aboriginal Veterans Monument in Ottawa. [Stephen J. Thorne]

“Elders who hold the knowledge about where a person is buried, they’re passing away and some do pass on that knowledge, some may not.”

Four years into it Pahud says his organization has “only touched the tip of the iceberg.” About 200 Indigenous markers have been installed in remote communities—and a few overseas—and some 300 more are on order, a process delayed by the COVID pandemic, which cut into the availability of granite.

Trujillo said there is a sense of urgency surrounding the program because many of the graves that are marked by wooden crosses, which are weathered and fading.

“Also, a lot of the Elders who hold the knowledge about where a person is buried, they’re passing away and some do pass on that knowledge, some may not. So, they’re crucial people for us to work with.”

The film follows the journeys of three Indigenous researchers documenting graves, interviewing locals and ultimately placing headstones during emotional ceremonies in small cemeteries throughout Quebec, Saskatchewan and the Northwest Territories.

Pahud and Trujillo are hoping the film, soon to be available on the Last Post Fund’s website, will help create awareness.

Working with Veterans Affairs Canada and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, the 114-year-old Last Post Fund has, overall, identified and placed headstones on nearly 8,000 unmarked graves, with another 2,000 applications in-house. Over its history, it has helped nearly 150,000 vets dating from the Boer War, both world wars and Korea through present-day.

The National Field of Honour in Pointe-Claire, Que., owned and managed by the Last Post Fund since 1930, is the final resting place of more than 22,000 Canadian and Allied veterans and their loved ones.

Advertisement