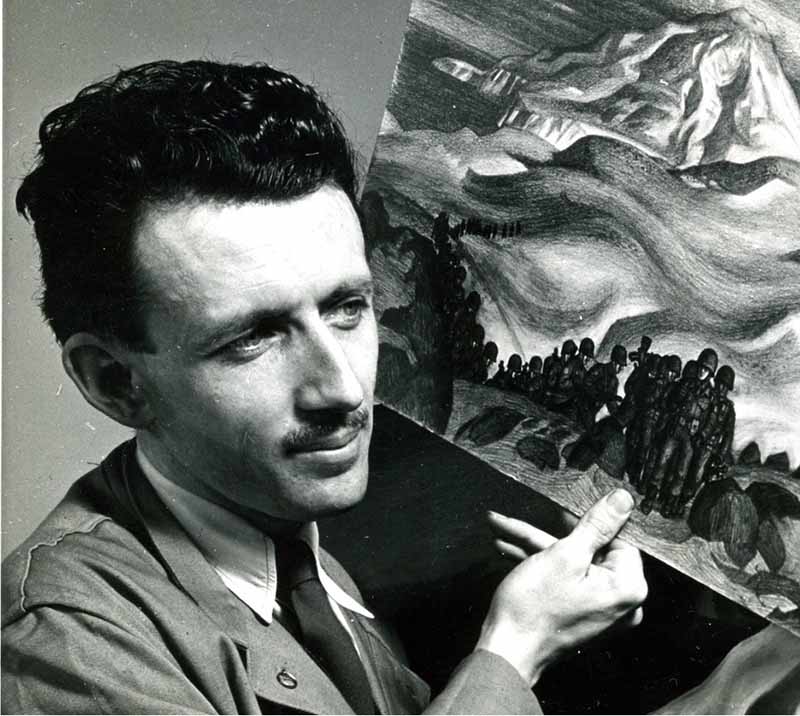

E.J. Hughes with graphite cartoons for his War Records oil paintings (1946). Photograph by Malak.

E.J. Hughes attended the Vancouver School of Art from 1929-1935, and was recognized as the most talented artist of his generation on the West Coast. But the Great Depression made an art career impossible at that time. Reflecting on the years he had enjoyed as a cadet, he enlisted in the army on Aug. 30, 1939, just days before the commencement of the Second World War.

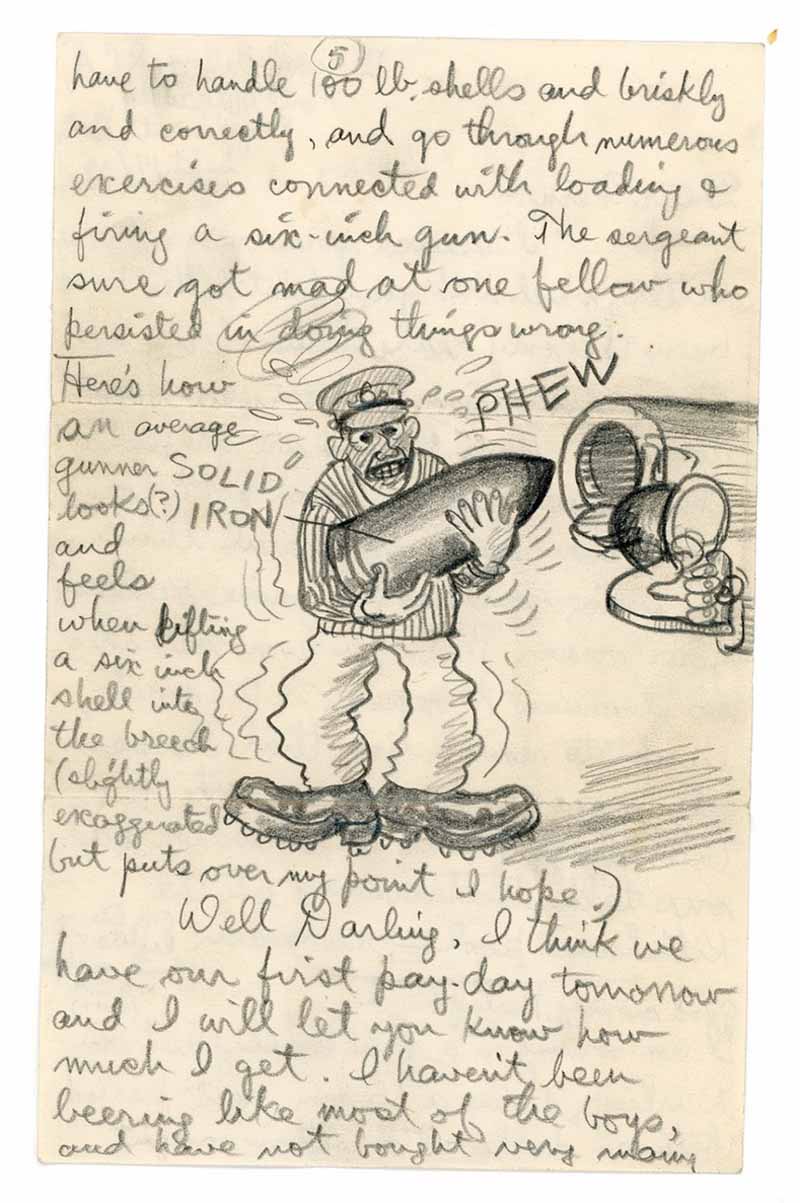

Hughes had joined the artillery, but almost from the start he had higher ambitions. Through his teachers, Fred Varley and Charles H. Scott, Hughes was aware of the War Art Program of the First World War, and he began writing to his superiors, asking for a role as a war artist. At the time, there was no war art program, but early in 1941 he was posted to Ottawa as one of the first three “service artists” in the Canadian Army.

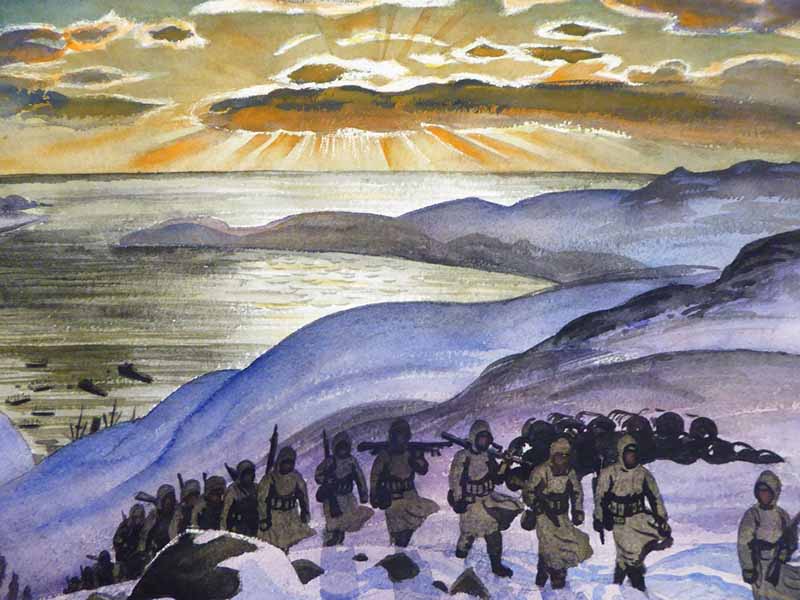

After two winters recording the life of the troops in Ottawa and Petawawa, Hughes was stationed in England in March 1942, where he continued to make detailed drawings and watercolours. In February 1943, the Canadian War Art Program became official. He was posted back to Ottawa that summer and, in November 1943, was sent to Kiska, the westernmost of the Aleutian Islands off the coast of Alaska. The freezing conditions and hours of darkness during the months he spent there were not conducive to making detailed drawings, so he transformed his style and began creating small oil paintings on wooden panels.

On his return to Ottawa in 1944, Hughes felt the influence of other war artists whose work was bigger and bolder than his. Two visits to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, as well as reading books about Mexican muralists, inspired him to create larger oil paintings, with strong tonal contrasts and a focus on the men.

From 1944-1946, Hughes served as the administrative officer of the War Artists’ Studio in Ottawa, and as a result, he was the last of all the artists to be demobilized. Thus, he was the first, the last and the longest serving of all Canadian War Artists in the Second World War—and the most prolific.

Everything Hughes created during his years of war service—a total of 541 paintings and drawings—was retained by the Canadian Army. In October 1971, the Canadian War Records were deposited in the new Canadian War Museum. Very little of the body of work Hughes created has been exhibited.

When Hughes returned to civilian life in late 1946, he was 33 years old and out of work. Despite his prolonged training and years of war production, he had never really sold a painting. Then, one day in 1951, Max Stern, the owner of the Dominion Gallery in Montreal, met Hughes and contracted to buy all the artworks Hughes produced. Since then, Hughes’s paintings have achieved great renown and hang in all the best Canadian art museums and private collections. They have on occasion sold for more than $2 million.

Text by Robert Amos from E.J. Hughes: Canadian War Artist, copyright © 2022. Reprinted with permission of TouchWood Editions.

“Route March, Early Morning (1943).” Watercolour 20 1/4” x 27” (51.0 x 68.7 cm).

“The Sentry, (1941).” Watercolour 16” x 9” (44 x 33.9 cm)

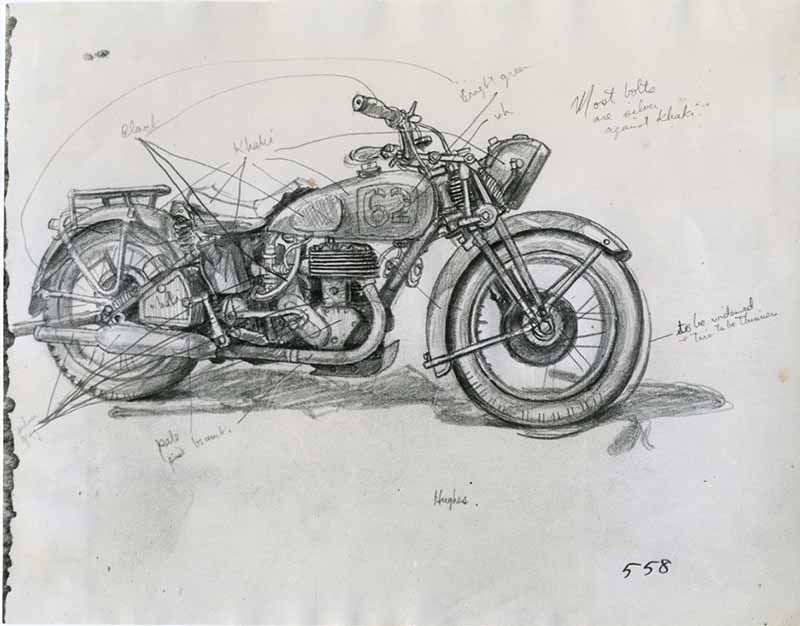

Motorcycle, (1942). Pencil 8” x 10” (20.3 x 25.4 cm).

“Patrol, Kiska, (February 1945).” Oil 30 1/4” x 36” (76.5 x 102 cm).

“to handle 100 lb. shells,” from a letter from E.J. Hughes at Fort Macauley to Fern Smith in Vancouver, September 1939. Ink.

Advertisement