Vincent Poggi painted this portrait of fellow Italian Canadian Erminio Ghislieri at the internment camp in Petawawa, Ont., in 1942.[Vincent Poggi/CWM/20020203-002]

Reflections on the internment of Italian Canadians during the Second World War

In the Piazza Dante across from Ottawa’s St. Anthony of Padua Church, where services are held in English and Italian, is a memorial wall with two columns of names: one for the names of local Italian Canadians who died serving Canada during the Second World War; the other of local men who were detained in internment camps.

In the early days of the war, the federal government of William Lyon Mackenzie King passed the War Measures Act and implemented the Defence of Canada Regulations. The regulations gave the government the authority to detain anyone deemed to be “acting in any manner prejudicial to the public safety or the safety of the State.”

In 1940, Italy declared war on Great Britain and France, and thereby their allies, including Canada. This immediately made some people question the trustworthiness of Italians who had recently come to Canada. Indeed, several Italian fascist groups and newspapers (namely Il Bollettino and the Dopolavoro) existed in Canada. And estimates suggest about 3,000 Italian Canadians were members of fascist groups at the time. However, in many cases these were memberships of convenience rather than ideology.

Still, some 31,000 Italian Canadians were labelled enemy aliens. They lost jobs, their property was confiscated and their businesses vandalized. In addition, more than 600 were arrested and sent to internment camps in Petawawa, Ont., Kananaskis, Alta., and Minto, N.B. In the end, however, no Italian Canadian was ever convicted of crimes against the state.

It was a great injustice, like the treatment of Canadians of German and Ukrainian descent during the First World War and of Japanese descent during the Second World War.

“For King, it was always easier to do nothing, to sacrifice a minority to satisfy the demands of the majority,” wrote historian Tim Cook in his book Warlords, referring to the refusal to accept Jewish refugees from the war.

Crowds watch as police raid the Casa d’Italia in Montreal to arrest Italian Canadians on June, 10, 1940. [LAC/PA-140527]

Some 31,000 Italian Canadians were labelled enemy aliens. More than 600 were sent to internment camps.

On May 27, 2021, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau rose in the House of Commons to apologize to the Italian Canadian community for the internments.

“During the Second World War, 31,000 Italian Canadians were labelled enemy aliens, and then fingerprinted, scrutinized and forced to report to local registrars once a month,” said Trudeau. “Just over 600 men were arrested and sent to internment camps, and four women were detained and sent to jail.

Newspapers such as Il Bollettino shared fascist ideology. [York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections]

“When the authorities came to the door, when they were detained, there were no formal charges, no ability to defend themselves in an open and fair trial, no chance to present or rebut evidence. Once they arrived at a camp there was no length of sentence. Sometimes the internment lasted a few months. Sometimes it lasted years, but the impacts—those lasted a lifetime,” Trudeau continued.

“To stand up to the Italian regime that had sided with Nazi Germany, that was right, but to scapegoat law-abiding Italian citizens, that was wrong.”

It was not the first time a prime minister had apologized for those actions. Prime Minister Brian Mulroney had also done so during a meeting of the National Congress of Italian Canadians in Toronto in 1990. And between 2008 and 2013, Canadian Heritage’s Community Historical Recognition Program, created during Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s tenure, made $5 million in grants available for projects to commemorate the experiences of Italian Canadians during the Second World War. The program funded an archive at the Columbus Centre in Toronto, two books published by the Association of Italian Canadian Writers and a sculpture by artist Egidio Vincelli that stands at the entrance of the Casa d’Italia in Montreal, among other initiatives.

Today, approximately 1.6 million Canadians have Italian heritage, one of the largest Italian diasporas in the world. The magnificent St. Anthony of Padua Church, long the social centre of Ottawa’s Italian Canadian community, was designed by Montreal-based artist Guido Nincheri. It boasts several magnificent stained-glass windows he created.

Born in 1885 in Prato, Italy, a town outside Florence, the artist came to North America in 1913. “Back in Italy, his father virtually kicked him out of the house. He didn’t want his son to grow up to be an artist,” said Guido’s grandson Roger Nincheri.

Still, he persisted and made his way to Florence where he studied art and began painting frescoes. He landed in North America in New York.

“He wanted to go to Argentina, but the war was on,” said Roger, who has written about his grandfather’s work.

In Montreal, Nincheri worked with renowned stained glass artist Henri Perdriau, decorating churches and other buildings in Canada and the U.S. Nincheri practised his glass art and painted frescoes in more than 100 churches, including the Church of Saint-Léon-de-Westmount in Montreal, now a national historical site. His window in Vancouver’s Holy Rosary Cathedral was featured on a Canadian stamp in 1997. And Pope Pius XI called Nincheri “the church’s greatest artist of religious themes.” By coincidence, he had also painted a fresco in Montreal’s Church of the Madonna della Difesa, which depicts Italian dictator Benito Mussolini on horseback among Christ’s followers.

The art of Guido Nincheri [Wikimedia]

Nincheri had painted a fresco in Montreal’s Church of the Madonna della Difesa, which depicts Mussolini.

But once Italy declared war on Canada, Nincheri, like so many other Italian Canadians, was arrested.

He was in Baie-Comeau, Que., working at Église Sainte-Amélie at the time. He was sent to the internment camp in Petawawa, Ont. Authorities offered no explanation for his detainment.

The art of

Guido Nincheri has appeared on stamps

[Canada Post]

“He was called a traitor and spat on while he was on the train going there,” said Roger. Nonetheless, he was allowed to do some artwork while interned, even giving some of his work to the camp commandant. “After the war, he had to get away and moved to Providence in Rhode Island…he continued to come back to Canada to work, but he never talked about his time in Petawawa.”

Once in the camps, the men were given blue jumpsuits with a red circle on the back. Internees were kept in wooden barracks and worked on roads and logging. Members of the Veterans Guard of Canada, a unit made up of First World War soldiers who were then considered too old to serve overseas, watched over them.

Among those who helped push for the Trudeau apology was historian Joyce Pillarella, the granddaughter of an internee. Pillarella interviewed dozens of descendants like herself to find out how their lives are still affected by the internments.

“Hiding one’s ethnicity was a common survival technique,” wrote Pillarella in the Toronto Star in 2021. “Italian became the enemy language and speaking it became a marker of disloyalty. Changing one’s name was almost a must, to avoid hostility or to get a job. Identity had consequences.

“The apology is about dignity, not dollars,” she wrote. “Make no mistake, the internment of Italian Canadians does not define Canada, but the apology does. It acknowledges that the failure to recognize basic rights of people is un-Canadian. It demonstrates that Canada is not afraid to face the past and learn important lessons to protect and preserve our democracy and freedoms.”

The “King” of Camp Petawawa

Italian Canadians, including mobster Rocco Perri (back row, second from left), at the internment camp in Fredericton

in 1942. [The Giacomelli Family ]

One of the Italian Canadians interned in Canada during the Second World War was the notorious “King of the Bootleggers,” Rocco Perri. Until then, the Hamilton gangster had had a remarkable ability to stay out of prison.

Perri and his common-law wife, Bessie Starkman, ran a bootleg business until Prohibition and opportunity knocked. The Ontario Temperance Act was declared in 1916. Prohibition was declared nationally in 1918 and the U.S. followed suit, introducing it in 1920. Hypocritically, Canada allowed distilleries to continue producing their product for foreign exports.

Perri’s business flourished as he supplied Canadian whisky to markets in Ontario and the U.S. He became a leading figure in organized crime in southern Ontario and was under routine police surveillance. Suspected of several crimes including murder, the police rarely intervened in his activities, in part because many officers were on his payroll.

In the late 1920s, he was called to testify at the Royal Commission on Customs and Excise focusing on bootlegging and smuggling. Afterward, he was charged with perjury and served five months in jail.

Prohibition ended nationally in 1919 and in Ontario in 1922, although it continued in the U.S. until 1932. Still, Perri continued to be a major figure in organized crime, branching into narcotics and prostitution.

In 1940, Perri and his brother Mike were arrested as enemy aliens and sent to Camp Petawawa. He was released on Oct. 17, 1943. A little more than a year later, on April 23, 1944, the “King” disappeared and was never seen again.

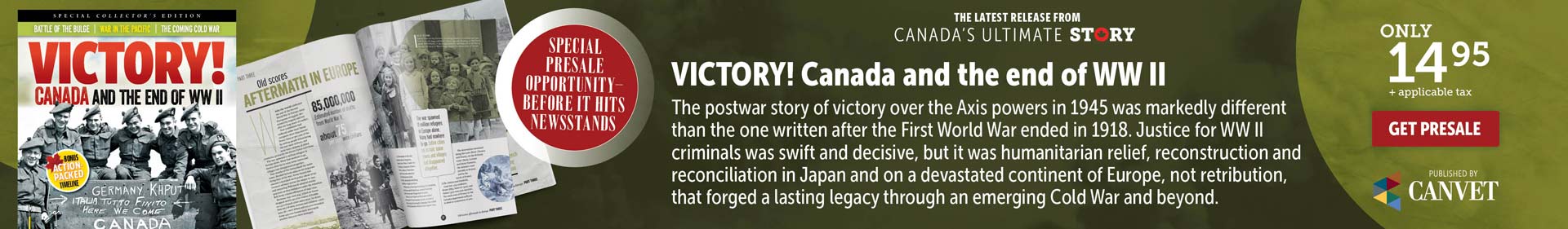

Advertisement