Female pilots had broken endurance, altitude and speed records before the war, but their hopes of a wartime flying career were stopped in Canada by a thick glass ceiling

Canadian pilot Helen Harrison found a wartime flying career with the British Air Transport Auxiliary. [Canada Aviation and Space Museum/CAvM6034; RAF Air Historical Branch/Wikimedia]

Helen Harrison was a child when she decided to become a pilot.

Born in Canada in 1909 but educated in England, by the age of 27 she had earned her pilot’s licence, qualified as a commercial pilot and received seaplane and instructor’s ratings. The Royal South African Air Force offered her an instructor’s course on military aircraft; while there she also earned an instrument flying rating.

“When I applied to the RCAF, I was rejected because I wore a skirt”.

She became the first woman in the British Empire, it is believed, to instruct on military aircraft after she was hired to train reserve air force pilots in South Africa.

At the beginning of the Second World War, Harrison tried to join the Royal Air Force, but was rejected. She got the same reception when she returned home in 1940 to try her luck with the Royal Canadian Air Force.

“When I applied to the RCAF, I was rejected because I wore a skirt,” she said in Lois K. Merry’s Women Military Pilots of World War II. “I was furious. I just couldn’t believe it. I had 2,600 hours, an instructor’s rating, multi-engine and instrument endorsements, a seaplane rating and the experience of flying civil and military aircraft in three countries. Instead they took men with 150 hours.”

Harrison then pinned her hopes on the establishment of a women’s auxiliary air force that would allow women, as in other Allied countries, to ferry military planes between factory airfields and military air bases.

But when the Canadian Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (CWAAF) was established by order-in-council in 1941, its function was “to release to heavier duties those members of the RCAF employed in administrative, clerical and other comparable types of service employment.”

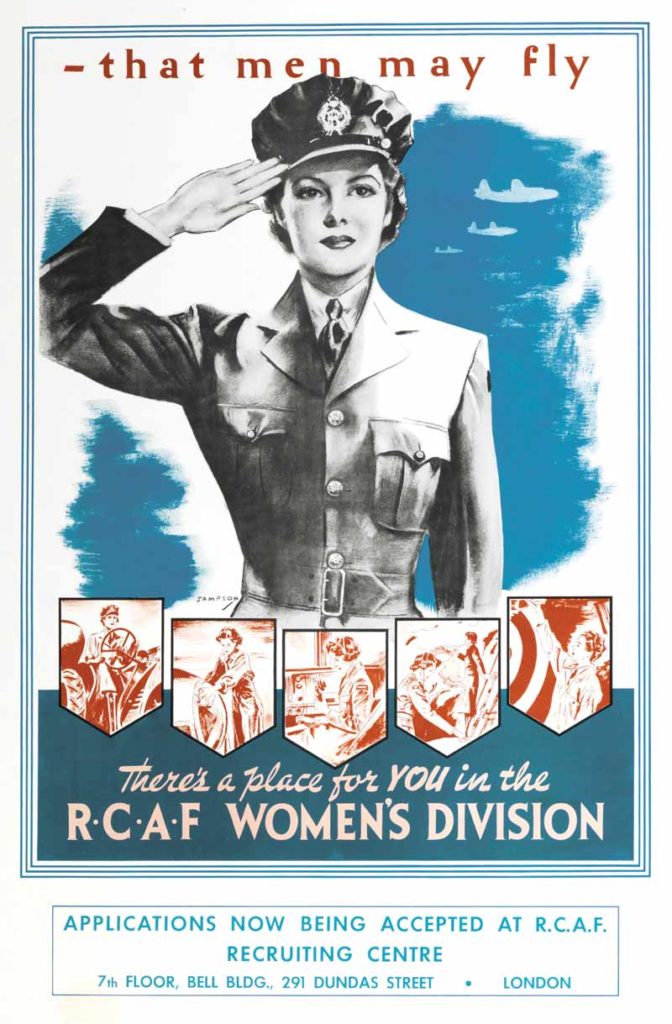

Things did not improve for female pilots when CWAAF was integrated with the RCAF in 1942 and renamed the Royal Canadian Air Force (Women’s Division). Its motto was ‘We Serve that Men May Fly.’

Recruitment posters helped persuade more than 17,400 recruits to join the division. [CWM/20090063-008]

Only a handful of very determined Canadian female pilots managed a wartime flying career. And they had to leave the country to do it.

During the Great Depression, there weren’t enough jobs to go around and many occupations were barred to women. The war changed that. Women filled civilian jobs left vacant by men who signed up for the services, and the services themselves opened to women, freeing up servicemen for combat.

During the Second World War, more than 17,400 recruits volunteered to serve in the Royal Canadian Air Force (Women’s Division). Most joined to serve their country, but many joined because of the benefits—which included room and board—and wages, even though early in the war, they were only two-thirds of men’s pay (later boosted to four-fifths).

The RCAF Women’s Division lines up for inspection in Halifax in 1944. [Glennis Boyce/The Memory Project]

Initially restricted to jobs as telephone operators, cooks, transport drivers and hospital workers, as the war progressed, more and more occupations previously considered men’s work were opened to women.

All the doors were shut in female pilots’ faces, but in 1942 a couple of windows opened.

Women became instrument mechanics, parachute riggers, air photographers, intelligence officers, weather observers, wireless operators, meteorologists, air traffic controllers. In all, 69 of 102 air force trades were open to women—but flying wasn’t among them.

All the doors were shut in female pilots’ faces, but in 1942 a couple of windows opened.

Patricia Holden (left) was delighted to discover photography was one of the occupations open to her in the RCAF Women’s Division. [Patricia Collins (née Holden)/The Memory Project]

Faced with a severe pilot shortage, in 1942 the United States began training licensed women pilots for the Women Airforce Service Pilots. Called WASPs, they served everywhere a male pilot would—except in combat. Duties included ferrying military aircraft, testing overhauled planes and towing targets for gunnery practice.

More than 25,000 women applied, but only 1,800 were accepted and 1,074 graduated. Some applicants were from Canada, but they lacked a key qualification—U.S. citizenship.

But Virginia Lee Warren was born in Canada of American parents and had learned to fly in Manitoba, ferrying men to a gold mine accessible only by air. She qualified for her pilot licence and became a WASP in 1943, making the cut despite being two years underage and a quarter-inch too short, she said in a film on YouTube. During the war, she ferried planes and qualified as a test pilot.

“I flew Harvards (from Canada), the B-24 from the Ford Factory in Detroit, Lysanders, Piper Cubs, twin-engine Cessnas (UC-78), BT-15 (basic trainers), and a couple of flights in the B-17, AT-7 and AT-10.”

In 1942, North American pilots were recruited for the British Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA), a civilian operation that ferried more than 300,000 military aircraft within Great Britain during the war. Some 1,200 pilots were recruited; 168 were women, five were from Canada. A number of female former ATA pilots, including Jaye Edwards of Lynn Valley, B.C., emigrated here after the war.

Air Transport Authority pilot Jaye Edwards emigrated to Canada following the Second World War. [CTV News]

In April 1942, Helen Harrison became the first female Canadian ferry pilot with the ATA—known as Attagirls. Returning from leave in Canada, she was one of the few women to co-pilot a Mitchell bomber across the Atlantic.

“I was happy as a lark and higher than a kite,” she was quoted in She Dared: True Stories of Heroines, Scoundrels, and Renegades by Ed Butts. “The most difficult part of the flight was using the tube to go to the bathroom,” she said. “I got a little damp.”

Marion Powell Orr and Violet Milstead, whose love of flying made them fast friends, soon followed Harrison. Both earned their pilot’s licence in 1939.

In 1942, Orr, the second woman in Canada to qualify as an air traffic control assistant, was manager and chief flight instructor at the St. Catharines Flying Club in Ontario. The RCAF turned down her application to serve as a wartime flight instructor, even though she had trained military pilots as a flight instructor at Barker Field in Toronto. But she was hired as a controller in the Goderich RCAF base.

Milstead worked at a wool shop, saving pennies for flying lessons; she earned her commercial licence in 1940 and instructor’s rating in 1941. By the time the ATA began recruiting, she had amassed about 1,000 flying hours.

Orr and Milstead both passed flight tests administered by the RCAF and set off for Britain on April 19, 1943. Not only would they do the same job as men, but from 1943, female ATA pilots were paid the same as the men.

Orr flew her first ATA flight on June 2, 1943, and would fly dozens of different aircraft before war’s end, including Harvards, Hurricanes, Spitfires, Ansons, Swordfish and Tiger Moths. She delivered the planes from factories to bases and returned damaged aircraft to repair depots.

Pilots Marion Orr and Vi Milstead relax on the wing of a Harvard combat training aircraft. [Toronto Aviation History]

Milstead moved quickly up the ranks. ATA cadets were promoted to third officer upon completing training; Milstead held that rank for only six days before being promoted to second officer, and soon after became a first officer.

She flew trainers, fighters, bombers—four dozen different types of aircraft in all. She was the longest-serving Canadian ATA pilot, achieved the highest rank, and flew more hours than any other woman pilot. Just a shade over five feet tall, she frequently flew sitting atop a packed parachute so she could see out the cockpit.

ATA couldn’t train pilots in every one of the 147 different wartime aircraft, so the 70 most common types were divided into six classes. Pilots were trained on one aircraft in each class and considered to be qualified to fly all the other types in the class.

Each was given a Blue Book, a compendium of knowledge covering every airplane, and a blessing when piloting an unfamiliar aircraft for the first time.

“Good God, girl!” an RAF pilot said to Milstead who was about to get into a Beaufighter night fighter for the first time. “You can’t fly this plane from a book!”

“I can from my book,” she said, quoted in She Dared.

Orr read the book before her first flight in a Spitfire. “You just studied the book, started up and hoped for the best.… On takeoff, I was pressed so hard into the seat I couldn’t move. I was at 4,000 feet before I knew it,” she said in a 1976 article in Canadian Aviation.

Spitfires were her favourite to pilot; Tiger Moths were the trickiest of the lot. She flew Mosquitos, Blenheims, Beaufighters, Mitchells, Hawker Tempests, Hellcats and Spitfires—nearly 50 different types in all.

ATA pilots flew as many as eight flights a day in half a dozen different aircraft, through fog, storms and in the dark, navigating by dead reckoning to avoid the interception of radio transmissions in enemy-infested skies.

ATA pilots liked to say the acronym stood for ‘Anything to Anywhere.’ It was dangerous work—174 ATA pilots, 15 of them women, were killed.

“The difference between our training and RAF training is that we were trained to fly not just one type of single engine, but any type of single-engine planes,” said Edwards in a CBC interview in 2018.

Once she was caught in a snowstorm and got lost in fog. Her wings were icing up. “Airplanes are born to fly,” she said in a newspaper interview in 2018. “A little power and a little turn and that should take us back where we started from.”

Climbing out of a plane, Orr often saw men pretend to faint. Men “seemed to think they had a monopoly on all the air between the earth and heaven.… I soon learned that when a woman invades a man’s field, she must do the job better than a man if she is to be successful.”

The barriers were even higher for Elspeth Russell, the only Canadian female ATA pilot from Quebec. She was determined to fly for the ATA, even though she was not a pilot before the war, and civilian flying schools had shut down for the duration.

She flew with another pilot until she became proficient in the air, then amassed 150 solo hours. She applied to the ATA in 1943, and despite her inexperience, she was judged to be an above-average pilot. She too had lied about her age.

Russell started out ferrying light planes, but soon graduated to bombers. She ferried more than 30 different types of planes in her ATA career, including Spitfires, Mustangs, Hudsons, Hellcats, Wellingtons, Mosquitos, Beaufighters and Dakotas.

After the war, Canadian Attagirls had to compete for jobs with all the men with war flying experience. The determination that earned them pilot careers during the war served them afterward as well.

Russell married fellow ATA pilot Gerry Burnett in 1945, settling in Matane, Que., where she flew as a commercial pilot. The pair formed their own airline, Matane Air Services, in 1948. Before they sold the company in 1965, their fleet had grown from a Stinson 108 and Piper PA-12 to include a half dozen Cessna Cranes, a de Havilland Dragon Rapid, four Lockheed 10s and a DC-3.

Orr also went into business for herself.

“I had all that experience and I knew that I couldn’t put it to use in Canada,” she said in Merna Forster’s 100 More Canadian Heroines: Famous and Forgotten Faces. She worked for a time as a flight instructor, then became the first woman to own and operate a flying club, using her skills in aeromechanics to fix her own planes.

After selling her business in 1961, Orr became the first woman in Canada licensed to fly helicopters and shortly afterward earned her helicopter instructor’s rating. She was an instructor at Toronto Airways for a decade before she decided for the first time to retire—but she was back in the sky in no time, working as a freelance instructor.

By the end of her career, Orr had taught more than 5,000 students how to fly. Of her 21,000 logged flying hours, 17,000 had been spent as an instructor.

“I’d rather be 2,000 feet upstairs, than eat, sleep or get married.”

She stopped flying in 1994 and died in a vehicle collision in 1995 in Peterborough, Ont.

Meanwhile, Orr’s pal Milstead had become “Canada’s only woman bush pilot and one of the few females in this country to make a peacetime living jockeying aircraft for pay,” wrote Bruce McLeod in “Bush Angel,” a 1948 article in Maclean’s.

“I’d rather be 2,000 feet upstairs,” said Milstead, “than eat, sleep or get married.”

But she did marry—a pilot, of course. In 1947, she and her husband moved to Sudbury, Ont., working as charter pilots and flight instructors. They flew to mining camps in all weather, carrying workers, equipment and supplies in Cessna and Fairchild Husky machines.

“A mining executive who has flown with Violet Milstead told me, ‘She’s a natural,’” wrote McLeod. “‘She flies a plane like she was part of it. I figure it’s safer sitting up there with Vi Milstead and the birds than it is walking across a Sudbury intersection.’”

Milstead and her husband worked out of Sudbury, Windsor and the Muskoka Lakes before a brief stint in Indonesia, where she hit the glass ceiling again. She was allowed to fly in that country, but they wouldn’t hire a woman as an instructor. So the pair returned to Canada when her husband’s contract was up. But her career as a pilot was over.

Milstead held office jobs until she and her husband retired in 1973, enjoying piloting their own Piper Cub. Milstead’s husband died in 2000, and she followed in 2014, aged 95.

After deactivation of the WASPs, Warren returned to Canada and married in 1945, giving up her flying career. She died in 1995.

Harrison went on flying professionally for decades. She flew as a demonstration pilot after the war, then worked as chief flying instructor for a number of flying services in British Columbia and trained floatplane pilots until her retirement in 1969.

Harrison said that during the Second World War, her fellow female ATA pilots often wished they could fly in combat, as Russian women did.

In Canada, that was a long time coming. Women were accepted as pilots in the RCAF in 1979, but it was 1987 before female fighter pilots took the controls of combat aircraft, at long last shattering the glass ceiling.

Flying a desk

Even though there was a shortage of pilot instructors, female flight trainers were also grounded during the Second World War.

When wartime fuel rationing forced civilian flight schools to close, flight instructor Margaret Littlewood lost her job at Gillies Flying Service near Toronto. She hoped to go on to train military pilots and applied to all 10 British Commonwealth Air Training Plan Air Observer Schools.

She received nine rejections before First World War flying ace Wilfrid (Wop) May hired her at No. 2 Air Observer School in Edmonton.

“He was not a man to dilly-dally with problems,” Littlewood is quoted on the Edmonton City As Museum Project website. “He thought I was qualified, and he didn’t care that I was a woman.”

But Littlewood was destined to fly a desk during the war.

She became the sole female instructor on the Link Trainer, a flight simulator used by the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan to teach instrument flying to male pilots.

Even though she had trained pilots to fly, Margaret Littlewood (above) ended up grounded during the war, serving as a flight simulator instructor. [Alberta Aviation Museum]

The simulator turned and tilted, replicating the feeling of flying. Inside the simulator’s cockpit, trainee pilots used an instrument panel to control the flight. Outside, Littlewood plotted courses for them, using external controls to simulate bad weather and emergencies.

Male trainers soon stopped scoffing as she calmly taught student pilots how to regain control after they had gotten into trouble in the simulator. She logged 1,200 instruction hours with 150 students in Edmonton and at RAF Ferry Command Centre in Dorval, Que.

After the war, Littlewood earned commercial pilot licences, but ended her flying career in 1954. She worked for the federal transport ministry until she retired in 1980. She died in 2012, aged 96.

Advertisement