The first Canadian-planned attack of the war was at Mont Sorrel, Belgium, in June 1916

Canadian troops advance under cover of smoke during the Battle of Mont Sorrel in Belgium in 1916. [Henry Edward Knobel/DND/LAC/3194767]

As May 1916 ended, the Germans clearly were planning an attack against the Canadian Corps front on the easternmost projection of the Ypres Salient in Belgium.

Extending for just over two kilometres from Mont Sorrel in the south, past Hill 61 and Hill 62 (Tor Top) and through to Sanctuary Wood in the north, heights of land here provided the easternmost points of observation of German rear areas. Observatory Ridge extended one kilometre westward from Tor Top into the heart of the salient. If this territory were lost, the Germans could dominate the salient and force its abandonment.

These were the stakes as Canadian and British intelligence staff studied German activity.

Throughout May, German sappers extended trenches toward each side of Tor Top and dug a connecting trench 50 metres ahead of their front line. Royal Flying Corps detected a new trench system in the German rear that mirrored the Canadian works around Tor Top. A buildup of large-calibre trench mortars and other artillery further indicated an attack was pending.

Offsetting this activity was a lack of the additional infantry that normally presaged an offensive, so no serious defensive preparations were undertaken.

It didn’t help that Lieutenant-General Edwin Alderson had been sacked in May over the April defeat at the Saint Eloi craters. He was replaced by Lieutenant-General Julian Byng.

“Why am I sent to the Canadians?” wrote Byng. “I don’t know a Canadian. Why this stunt?” Byng ultimately exerted a calm, commanding hand, but as May turned to June he was still getting settled.

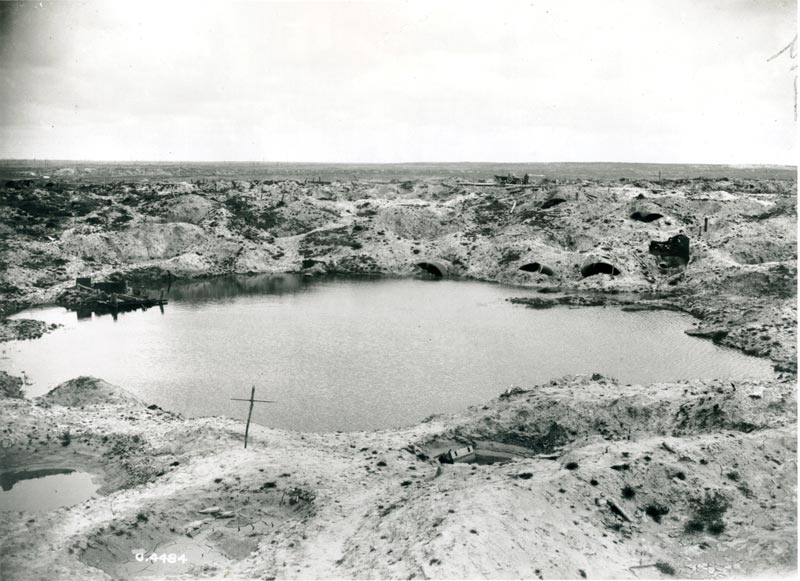

The Battle of Mont Sorrel came on the heels of setbacks during actions at the Saint Eloi Craters two months before. [DND/LAC/3329062 ]

The Canadians faced two divisions of the German XIII Corps. Their soldiers came from the independent kingdom of Württemberg, which joined the German Empire after the Franco-German War of 1870-71. After six weeks of stealthy preparation, the German artillery ceased fire for seven hours on the night of June 1-2 to allow wire-gapping parties to work free of friendly fire concerns. Then the artillery resumed fire.

At 6 a.m. on June 2, Major-General Malcolm Mercer and Brigadier Victor Williams of the 3rd Canadian Division strolled the front lines where the right flank of the 8th Infantry Brigade was held by the 4th Battalion, Canadian Mounted Rifles. Suddenly, the Württembergers unleashed “the heaviest [bombardment] endured by British troops up to this time.”

Having failed to win forward trenches with poison gas, the Germans adopted Allied tactics—smothering them with the sheer weight of shells fired from positions immediately behind the attacking infantry.

The 4th Battalion, CMR, was hardest hit. Their whole position, a German officer recorded, “was a cloud of dust and dirt, into which timber, tree trunks, weapons and equipment were continuously hurled up, and occasionally human bodies.” The 4th suffered 89 per cent casualties. Only 76 of 7o2 officers and men were uninjured.

Williams was wounded and captured. Ear drums shattered, a leg broken, Mercer died when struck by shrapnel. Leaderless at divisional and brigade levels—communications shredded—3rd Division was in disarray.

A sniper sights along a Ross rifle near Mont Sorrel in June 1916. The rifle’s shortcomings made it unreliable in front-line service, but some CEF snipers preferred it because of its accuracy. [Henry Edward Knobel/DND/LAC/3520927]

The crushing, unrelenting barrage lasted all morning. Then, a few minutes after 1 p.m., four mines exploded in front of the Mont Sorrel trenches and the German infantry struck.

Six Württemberg battalions attacked, with another five in support and six in reserve. More than 6,500 soldiers advanced through bright sunlight in four waves spaced 70 metres apart, the grey-coated troops moving at a leisurely pace, seemingly confident the Canadians had been obliterated.

Flowing over Mont Sorrel and Tor Top’s decimated trenches, they met only isolated bands of the 1st and 4th CMR. Fighting was often hand-to-hand, the Canadians desperately trying to hold while the enemy burned out resistance pockets with flamethrowers.

Breaking onto Observatory Ridge, the Germans overwhelmed three strongpoints and overran a section of 5th Field Battery, 2nd Brigade, Canadian Field Artillery—its gunners fighting to the last man with revolvers. These were the only Canadian Corps guns ever lost to the enemy. (The two 18-pounders were subsequently recovered.)

The German attack might have gone farther if not for staunch resistance on the right flank by the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry in Sanctuary Wood. Their determined defence cost the battalion 400 casualties, including 150 killed. Among the dead was Lieutenant Colonel Herbert Cecil Buller, the PPCLI commanding officer, shot while directing his troops.

He ordered that “all ground lost today will be retaken tonight.”

The disciplined Württembergers advanced to within 600 or 700 metres of their objective, then stopped, despite seeing the road to Ypres open. The salient might have been lost had they continued on.

Canadian soldiers rest in reserve trenches during the Battle of Mont Sorrel in June 1916. The Canadian Corps gained the enemy territory, but with 8,000 casualties. Germany had 5,765. [DND/LAC/3520931]

Instead, the 1st Canadian Division established a blocking line by nightfall, supported by the machine guns of the 10th Battalion and Canadian Motor Machine Gun Brigade.

The 3rd Division, however, was in terrible straits. Byng temporarily strengthened it with two brigades from 1st Division and two battalions from 9th Brigade. At 8:45 p.m., he ordered that “all ground lost today will be retaken tonight.”

The units struggled to reach start lines and the attack was postponed until 7 a.m. Six green rockets that were to signal the four-battalion advance suffered random misfires. It took 14 rockets to make up the six and, even then, two battalions never saw any.

Each battalion attacked alone, allowing fire to be concentrated against one and then adjusted to engage another. The largest Canadian attack to date turned into a chaotic mishmash worsened by men wearing gas masks that left them gasping for air.

Private A.Y. Jackson, later a Group of Seven artist, saw his lieutenant fall “in a huddled heap.” A comrade stared “in dismay at a great spurt of blood coming from his arm, which was only hanging by a few shreds of flesh.” Shrapnel struck Jackson’s shoulder, back and neck and he fell. The attack collapsed.

The Germans were within three kilometres of Ypres, and General Herbert Plumer of the British Second Army was determined to drive them back. General Douglas Haig, British Expeditionary Force commander, agreed.

Haig, however, was preparing for the Somme offensive and refused to return infantry to the salient. He provided only artillery and one infantry brigade. Firepower, not infantry, Haig insisted, would win the day and 218 guns were deployed. As the guns hammered German lines, the 1st Division prepared for an attack on June 6.

That attack was postponed by poor weather prohibiting aerial observers from registering the heavier guns. Then the German 117th Infantry Division launched a spoiling assault against Hooge. Although it was contained, the Germans gained control of most of Hooge’s ruins until they were roped off.

Lacking enough strength to regain Hooge and attack Mont Sorrel and Tor Top, Byng let the Germans keep Hooge.

The experienced 1st Division, led by Major-General Arthur Currie, would spearhead the main assault. Because of losses while supporting 3rd Division’s counterattack on June 3, Currie regrouped his strongest battalions into two composite brigades. The attack, postponed to June 13, would fall on a front stretching from Mont Sorrel to Sanctuary Wood.

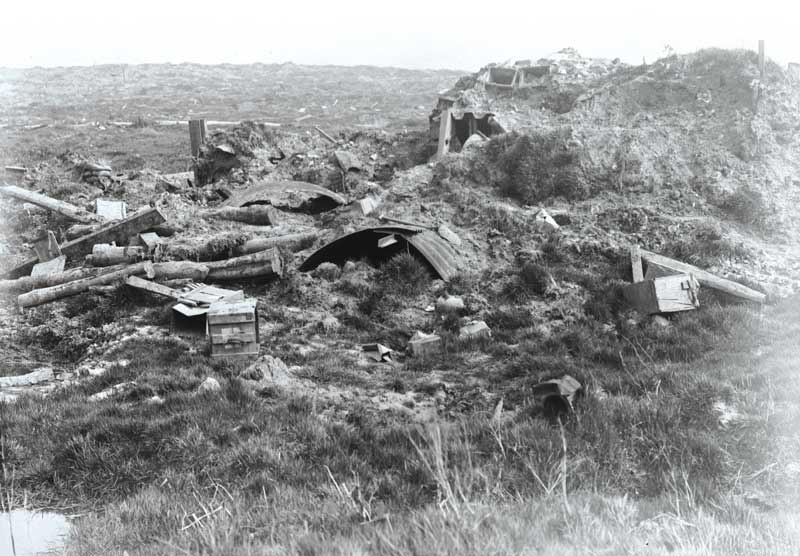

Ruins lie scattered around a battlefield post near Armagh Wood, northwest of Mont Sorrel. [DND/LAC/3329044]

Starting on June 9, Currie ordered a four-day bombardment that pounded the Germans for 30-minute intervals, then for 12 hours straight on June 12. As each wave of shelling lifted, the Germans rushed to their fighting positions. Then they were struck by renewed fire.

It was “a wet cheerless day, a steady misty drizzle soaking the clothes of the troops.”

“The losses of the [German] 120th and the 26th Infantry Division mounted in horrifying numbers…. What was constructed during the short nights was again destroyed in daytime,” reported a history of the 120th.

Both sides considered night attacks to be too prone to confusion, but Currie decided the tactic would give him the advantage of surprise. The attack on June 13 was led by four battalions.

It was “a wet, cheerless day, a steady misty drizzle soaking the clothes of the troops who, during those hours, lay in the open,” wrote Major Hugh Urquhart of the 16th Battalion, which moved into forming-up position on the night of June 11-12.

One Lewis machine-gun crew was reduced to two men at the very start.

Shells pounded the German lines, ceasing just 30 seconds before zero hour at 1:30 a.m. Ears ringing, the Canadians went forward. Lashing rain and thick smoke reduced visibility to a few metres.

This was no orderly advance by lines. Junior officers led clusters of 15 or 25. They wove past craters and shattered tree stumps, through holes in wire, slipping and falling in the mud. Rifles and revolvers clogged. Many soldiers were scythed down, but survivors kept going.

One Lewis machine-gun crew was reduced to two men at the very start. Five times, other men joined the two in operating the gun, only to be killed. But the two survivors reached their objective.

German opposition collapsed as the Canadians gained the enemy trenches. Many Württembergers were dazed and incoherent, wandering aimlessly with no rifles or other equipment. The artillery had done its job.

As dawn lit the sky, red flares signalled success. Almost all German gains of June 3 were lost. The price was about 8,000 casualties for Canadian Corps and 5,765 Germans losses.

The British official history recorded that the “first Canadian deliberately planned attack in any force had resulted in an unqualified success.” Mont Sorrel was a foretaste of the methods used by Canadian Corps that would transform it into the British Army’s shock troops.

Advertisement