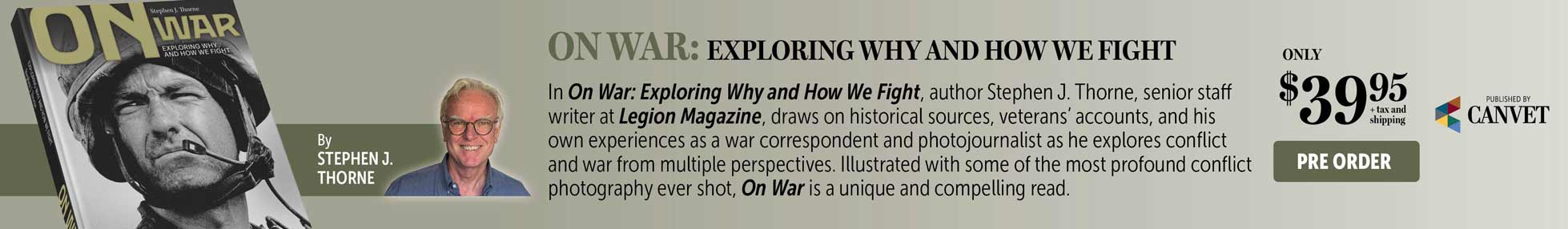

A Canadian soldier emerges from a cave containing an enemy stash of rockets and mortars in the mountains northwest of Kabul in 2004. Combat engineers blew up the cache and destroyed the cave. [CP/STEPHEN J. THORNE]

The Washington Post’s exposé on the Afghanistan Papers provides overwhelming evidence of the war’s shortcomings, detailing a litany of mistakes, failures and lies during the more than 18 years NATO forces have been fighting in the landlocked mountains and deserts that have over centuries become known as the graveyard of empires.

The revelations, if one can call them that (all wars, after all, are steeped in lies), have given pause to those who have not previously afforded Canadian involvement in Afghanistan much critical thought and emboldened the pundits and peace advocates who questioned it from the beginning.

But did the 158 Canadian soldiers known to have been killed between 2001 and our withdrawal in 2014 die in vain? Do the wounded suffer physically and mentally for no justifiable reason? Were Canada’s humanitarian efforts wasted? Could the billions the Afghan war cost Canadian taxpayers have been better spent elsewhere?

The answer to all of these questions, I contend, is No. To the degree that any war is justifiable, it was clear that Afghanistan’s role in the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, demanded a response. Anything less would have been naive and irresponsible in the face of an uncompromising enemy.

Canadian troopers prepare armoured vehicles for patrol near Kabul in 2003. Canada’s responsibilities grew as the Afghanistan mission progressed. [CP/STEPHEN J. THORNE]

Twenty-six Canadian civilians were among the 2,977 people killed on 9/11. Reason enough to hit back at the people and resources behind the al-Qaida terrorists who planned and engineered the attacks. Afghan Taliban and opium poppies were those people and resources.

Almost two decades later, the Taliban has not been eliminated and the poppy industry has not been eradicated. On the contrary, Afghan poppies currently feed more than 80 per cent of the world’s opium supply, and the Taliban appear poised to negotiate a new role in the country of their birth. ISIS, meanwhile, has overtaken al-Qaida as Enemy No. 1.

What the coalition effort in Afghanistan lacked was the key element to any military victory: commitment.

Within a year of the Afghanistan invasion, the Bush administration’s attention was riveted on Iraq, according to Dov S. Zakheim, a former U.S. undersecretary of defence and now a senior adviser at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Administration claims that Saddam Hussein was a player in al-Qaida and that he harboured weapons of mass destruction turned out to be bogus, but that didn’t curb escalation of the war in Iraq.

Whether the American higher-ups ever truly believed those assertions or if they were simply a ruse remains debatable. But what is certain is that Iraq demanded more of U.S. forces than George W. Bush et al anticipated, and it diluted American resolve and effectiveness in Afghanistan.

President George W. Bush addresses America from the deck of the nuclear aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln on May 1, 2003, declaring “mission accomplished” in Iraq. Almost 17 years later, the war continues. [STEPHEN JAFFE/Getty Images]

Ottawa had no choice but to send troops to Afghanistan; once there, they did what was asked of them, in spades. If Canada wants a seat at the table, if it expects to influence decision-making beyond its own borders, then it has to step up when circumstances demand it. War is never the preferred option—it is sad that it is an option at all—but it is sometimes the necessary one. That’s reality.

The Afghanistan adventure was also the victim of mission creep. Instead of focusing solely on eradicating the Taliban and al-Qaida, the coalition became distracted and mired in nation-building, possessed by the misguided idea that it could impose American-style democracy and culture on what remains essentially a feudal society run by corrupt and violent warlords.

No western democracy has the resources or the resolve to undertake such a daunting task. It takes generations to change the course of an ancient nation like Afghanistan, or the kind of mass grassroots movement that is well-nigh impossible in a country so isolated and fractious.

The Canadian public, which can be its own kind of fractious, demonstrated a rare unanimity in its support for its troops fighting overseas, though its enthusiasm for Canada’s participation in the war began to wane as the casualties mounted.

Their time there provided Canadian troops with invaluable experience, garnered them new profile and respect among Canadians and our allies, and it catapulted the military into a new era of warfighting. In the process, Afghanistan also silenced the echoes of the Somalia scandal and dispelled the myth that Canadian soldiers are only good for peacekeeping.

Granted, many Afghanistan veterans have left the forces in the years since, and Ottawa has demonstrated little appetite for putting the experience that remains within the ranks to practical use beyond mentoring troops in Ukraine, Latvia and, until recently, among Kurdish forces in Iraq.

But institutional memory is long, and the impact of the Afghanistan experience will reverberate for decades—in the tactics and strategies the military employs in the inevitable wars to come; in the equipment it chooses to buy to fight those wars; and in the care it administers those who live with the fallout.

For those who blazed those trails and now live with the fallout of Afghanistan, it’s the seemingly small, somehow Canadian, triumphs that must serve to help heal and console—the well that brought water to a parched village; the schoolhouse that now teaches young girls; the minefield that’s been cleared; the lives that were improved; the lives that were saved.

These are no small achievements. The big-picture stuff is beyond the reach of individuals.

Advertisement