Some 25,000 Canadians served in Korea. Sixteen months ago, 7,200 survived, average age 86.

Here are the last surviving veterans of Canada’s previous wars:

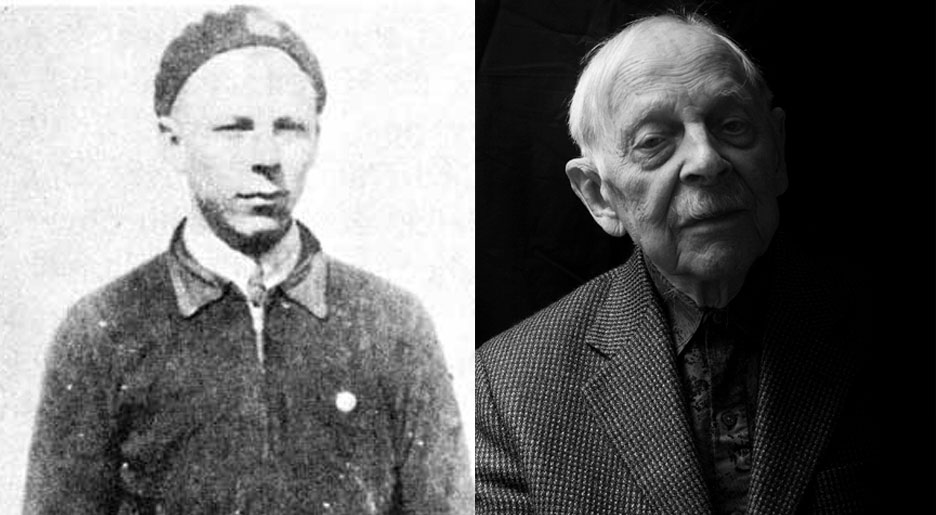

Jules Paivio, Canada’s last living veteran of the Spanish Civil War, died on Sept. 4, 2013. He was 97.

Pavio was a soldier, architect and teacher at Ryerson Institute of Technology in Toronto—the last surviving member of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion, a group of Canadians who fought with the XV International Brigade on the war’s Republican side.

More than 1,500 Canadians fought the fascist uprising led by Francisco Franco against Spain’s democratically elected government, the highest proportion of a population to volunteer in Spain other than the French.

Born near Port Arthur, Ont., and raised in Sudbury by Finnish parents, Paivio left for Spain at 19. He was captured, saved by an Italian officer from execution, and kept in a prisoner-of-war camp. The Spanish government granted him honorary citizenship in 2012.

“What does it do to you, not to be shot by a firing squad?” his son, Martin, asked.

In his father’s case, it gave him a deep love of life, said Martin. His postwar years involved a lot of heartbreak, including deaths of three children, MacLean’s Magazine reported. But Martin said Jules lived with a “glow of life” about him.

“He stayed in touch with other veterans and helped drive a campaign to get a monument to Canadians who fought in the war erected in Ottawa,” Michael Petrou wrote. “He told me that once a desire to help people who are oppressed gets inside you, it never really leaves.”

Paivio trained soldiers in map-reading and surveying during the Second World War.

John Babcock was the last Canadian First World War veteran to die, on Feb. 18, 2010. He was 109.One of 13 children, he was born in a barn in Frontenac County, Ont. Impressed by the salary of $1.10 a day (more than double the going labour rate) and two recruiting officers who quoted the poem The Charge of the Light Brigade, Babcock tried enlisting at age 15.

He made it to Halifax by train before he was stopped by the company commander, who sent him to the city’s peacetime barracks, where he dug ditches and loaded freight aboard army transports.

Claiming he was 18, Babcock volunteered when 50 recruits were summoned for the Royal Canadian Regiment. Officials quickly discovered he was only 16, however, and they placed him in a reserve battalion known as the Boys (or Young Soldiers) Battalion in August 1917. He was training in Britain when the war ended.

Lance-Corporal Babcock did not consider himself a veteran because he had never seen combat. He never joined any veterans’ associations but did collect a veterans’ pension and availed himself of veterans’ vocational training.

He moved to the United States in the 1920s, earning his sergeant’s stripes in the U.S. Army. He took out U.S. citizenship and became an electrician. He worked in the oil business and then moved on to natural gas before operating his own business as a mechanical contractor. Later, he worked for his son’s waterworks equipment wholesale business and did not retire until he was 87.

He earned a pilot’s licence at age 65 and his high-school diploma when he was 95.

At 100, he wrote an autobiography, Ten Decades of John Foster Babcock, which he distributed to family and friends.

In 2008, he wrote then-prime minister Stephen Harper asking for his citizenship to be reinstated. The request was approved and he was sworn in at his home in Spokane, Wash.

Almost 620,000 Canadians served in the First World War. “They should commemorate all of them, instead of just one,” Babcock said as hype surrounding his status ramped up. “I’m sure that all the attention I’m getting isn’t because of anything spectacular I’ve done. It’s because I’m the last one.”

He declined a state funeral.

George Ives served in the British-Canadian army and became known as the last surviving veteran of the Boer War. He died April 12, 1993, at the age of 111 years, 146 days—a British army record until it was broken in 2007 by 113-year-old First World War veteran Henry Allingham.Born in Brighton, England, he was eager to enlist after hearing that the British had been defeated at Colenso, Magersfontein and Stormberg. Trooper Ives fought with the Imperial Yeomanry of the British Army in South Africa from March 1901 to August 1902.

He had a scar on his cheek from a bullet that grazed him in battle. The wound was so slight it did not merit a mention in the official casualty rolls. He was discharged in England in September 1902 after serving for a year and 216 days.

“My job was to go over there and kill Boers,” he said years later. “You went to war to kill someone and they tried to kill you back.”

He emigrated to Canada on a coin toss—heads for Canada, tails for New Zealand—in 1903 with his father and bought a quarter section—160 acres—for $10. He was rejected from service in the First World War due to a heart murmur.

Ives moved his family to White Rock, B.C., in 1919, where he owned a farm and later worked in a shipyard building wooden scows.

He did chin-ups until well past 100. In a 1990 interview, Ives credited his longevity to a good wife, good genes and good work habits. His father lived to 99, his mother to 98.

William Mills, a Canadian army veteran of the Northwest Rebellion, died in 1971 at 105.

William Craig, a Canadian army veteran of the Fenian raids, died in 1951 at 101.

Richard Dixie, a Canadian militia veteran of the Rebellions of 1837 who fought in the Battle of the Windmill, died at 100 in 1916.

Sir Provo William Parry Wallis was a junior officer in the Royal Navy during the War of 1812. He served as temporary captain of HMS Shannon as it escorted the captured USS Chesapeake to Halifax Harbour after its captain was badly wounded and first lieutenant killed in one of the war’s most memorable confrontations.Eventually promoted Admiral of the Fleet, Wallis was still on the active list when he died at his country home in Funtington in West Sussex, England, on Feb. 13, 1892, just short of his 101st birthday.

His father, Provo Featherstone Wallis, was a clerk at the Royal Navy’s Halifax Naval Yard. His dad was bent on securing a naval career for his son and, in keeping with the rules for officers’ entry into the navy, he finagled his son official registration as an able seaman on the 36-gun frigate HMS Oiseau at the age of four.

In May 1798, young Provo became a “volunteer” aboard the 40-gun frigate HMS Prevoyante, then joined the 64-gun third-rate HMS Asia in 1799. He was promoted midshipman aboard the 32-gun fifth-rate HMS Cleopatra, the first ship on which he actually served. Thanks to his father’s manipulations, he had already amassed nearly a decade of seniority.

In February 1805, Cleopatra was captured by the French frigate Ville de Milan and the ship’s company taken prisoners of war. Wallis was freed a week later when Ville de Milan was itself captured by the Royal Navy.

His career soared. In order to prevent admirals from dying as paupers, a special clause in the retirement scheme of 1870 provided that officers who had commanded a ship before the end of the Napoleonic Wars should be retained on the active list until death. The six days Wallis commanded Shannon qualified him.

The Admiralty suggested he retire when he reached his late-90s, since being on the active list meant he was liable to be called up for a seagoing command. Wallis instead replied he was ready to accept one.

Wallis’s epaulettes are displayed in the Naval Museum of Halifax.

Advertisement