A grief-stricken American infantryman is comforted by another soldier in the Haktong-ni area of Korea. [Sfc. Al Chang, U.S. Army/Wikimedia]

![]()

![]()

For decades, politicians referred to the Korean War as the ‘Korean Conflict,’ as if the soldiers who fought and died on the battlefields of the disputed peninsula were somehow less soldierly or less dead if killed by conflict rather than war.

Some 2.5 million people died in the Koreas between 1950 and 1953, including 516 Canadians, and the war is not over yet. The armistice paused the fighting; 66 years later, there still has been no peace treaty signed to end it.

Officially, there was no declaration of war in Korea—it was a ‘police action’ (another euphemism)—so, technically, the politicians were correct, though ‘conflict’ suggests something more in the nature of a marital tiff than all-out war. Whoever came up with the phrase probably never saw a day of action in their life or, if they had, their motives are now clear.

Rest assured, those with vested interests in keeping political peace at home exploited the term, in part believing the public would pay less attention to what was going on halfway around the world than they would otherwise have done.

The more lasting consequence of that seemingly simple turn of phrase was that people also ignored thousands of Korean War veterans. For decades, they were overlooked and treated as second-class veterans by an ungrateful and war-weary public who assumed ‘police action’ and ‘conflict’ meant Korea was a walk in the park.

War is laced with jargon, euphemisms, acronyms and outright lies, much of it designed to smooth over or lessen the impact of what is actually going on.

“Euphemisms are frequently used…in order to avoid troublesome terms and phrases which possibly refer to something unpleasant or embarrassing,” wrote Sebastian Taugerbeck of Germany’s Universität Siegen in a paper entitled Military Euphemisms in Media Coverage.

“Euphemisms are also used frequently by governmental institutions—especially by the military—to hide unpleasant or disturbing ideas. These euphemisms play down the degree of violence, objectivize the enemy as well as the means of warfare and can lead to social double-thinking by forming a kind of code that distorts reality.”

Thus, an invasion becomes an ‘intervention,’ a ‘liberation’ or an ‘incursion.’ A coup is a ‘regime change.’ Protracted war becomes ‘overseas contingency operations,’ and drone assassinations are ‘targeted killings.’

Former United States president George W. Bush, vice-president Dick Cheney and others in their post-9/11 administration elevated the euphemism to high art as they escalated military operations overseas by falsely claiming in 2003 that Iraq had ‘weapons of mass destruction,’ or ‘WMDs’—practically a household term at the time.

The concept of defence was put on trial during this period when the Iraq War and subsequent military endeavours were described as ‘defending the homeland.’

“It would be reasonable to assume that this would be a reference to some kind of domestic military conflict,” David Watts observed in his 2013 paper Military Euphemisms in English: Using Language As a Weapon, “but the theatre for this defence was in reality thousands of miles away in a different continent.”

Watts notes the euphemistic use of the word ‘defence’ has increased in modern times: after the Second World War, the U.S. Department of War became the Department of Defense and, in 1964, the British War Office became the Ministry of Defence.

From left: Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, President George W. Bush and Vice-President Dick Cheney at the armed forces farewell tribute to Rumsfeld at the Pentagon in 2006. [Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images]

Prisoners were called ‘detainees’ and prisons like Guantanamo Bay, or the more palatable and upscale ‘Gitmo,’ were ‘detention facilities.’ Yet another deployment of U.S. troops was more ‘boots on the ground.’

“Since 9/11, can there be any doubt that the public has become numb to the euphemisms that regularly accompany U.S. troops, drones, and CIA operatives into Washington’s imperial conflicts across the Greater Middle East and Africa?” William J. Astore, a retired U.S. air force lieutenant-colonel, wrote for The Nation. “Such euphemisms are meant to take the sting out of America’s wars back home. Many of these words and phrases are already so well-known and well-worn that no one thinks twice about them anymore.”

Perhaps no military term has been more iconic or exploited in Canada than ‘peacekeeping.’ The label ‘peacekeeper’ is resented by many a blue-helmeted Canadian soldier who served in oblivion and at great peril in cesspools like 1990s-era Somalia and the Balkans.

United Nations peacekeepers in Rwanda in 1994. [The Australian]

Some United Nations forces were sent to stop ‘ethnic cleansing,’ which Watts describes as “possibly the most notorious euphemism to be employed in recent…military history.”

Rwandan African Union peacekeepers detain a suspect in the Central African Republic in 2014. [AP/Jerome Delay]

‘Ethnic cleansing’ came to be widely known in the early 1990s as the extent of brutality in the former Yugoslavia became public.

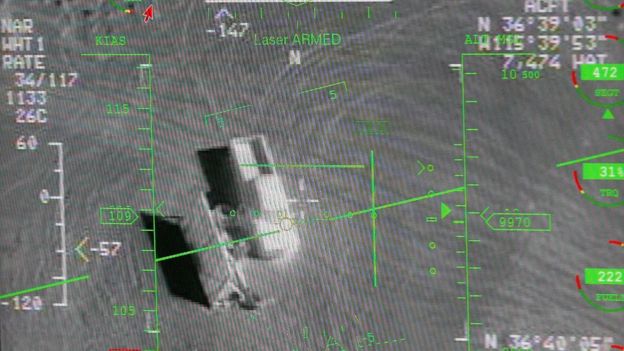

Coalition pilots enforced a ‘no-fly zone’ during the ‘military intervention’ in Libya. The tactic was approved by the UN Security Council on March 17, 2011.

“In reality, this tactic was to bomb and attack strategic and military targets from the air, but the term ‘enforcing’ makes no reference to military action, rather suggesting a simple policing of the area,” writes Watts. “Estimates on civilian deaths from this ‘enforcement’ vary wildly, but according to NATO at least 60 civilians were killed and 55 injured as a result.”

Some military euphemisms are more subtle than others.

‘Wounded’ seems a particularly military form of injury—inflicted by an enemy with the intent to kill. Yet the word that is increasingly applied to surviving battle casualties is the more benign ‘injured,’ which suggests that the sons and daughters, fathers and mothers sent overseas to defend democracy, freedom and the Canadian Way twisted an ankle or bruised a knee in the process.

‘Injured,’ however, in no way conveys the life-changing trauma inherent to many war wounds: amputations, disfigurement, permanent disability and chronic psychological torment.

In Vietnam, generals kept score by giving a daily, weekly or monthly tally of “body counts,” which did little to reflect what was actually happening (quite the opposite, actually) in one of the most disputed and futile wars of the 20th century. Combat dead were ‘killed in action,’ which was reduced to ‘KIA’—removing dead from the equation altogether.

Many Canadian casualties in Afghanistan were inflicted by roadside bombs or booby traps, an easily understood weapon, which the military insists on calling ‘improvised explosive devices,’ or the even more agreeable ‘IEDs.’

Some military euphemisms are designed to lessen the moral impact of mistakes, like ‘friendly fire’ or ‘blue on blue’ for same-side attacks that wound or kill allied soldiers. The phenomenon is a relatively recent product of more remote, industrialized warfare and, assuredly, there is nothing friendly about it.

‘Blue on blue’ derives from exercises in which NATO forces were identified by blue pennants and units representing Warsaw Pact forces bore red pennants.

An explosion destroys North Korean supplies during the blockade of Wonsan by American and South Korean warships in 1950. [Wikimedia]

Interestingly, such unintended consequences were relatively common during the bombing campaigns of the Second World War, but nobody seemed to care much except those who suffered the consequences.

‘Collateral damage’ gained widespread use during and after the Gulf War in 1990-91, when technology-driven militaries supposedly started going to great lengths to avoid unintended injury and damage.

‘Surgical strikes’ and ‘precision bombing’ imply sanitized perfection, and exactitude is what a more discerning public has come to expect from their militaries. When mistakes do come to light, there is hell to pay, at least as far as fickle public opinion can make it so.

Gulf War coverage was heavy with munitions–mounted camera video, giving the impression that ‘surgical strikes’ harm no one but the enemy.

Unscrupulous forces have, in recent decades especially, used innocent civilians and facilities such as schools and hospitals as ‘human shields,’ for self-protection and, when that does not work and civilians are killed, for propaganda purposes.

When things are not going well and public opinion turns against an administration’s wartime policies, it orders a troop ‘drawdown,’ which was once considered a ‘withdrawal’ which, in turn, was a substitute for ‘retreat.’

“The U.S. military and the civilian government it has browbeaten into hapless acquiescence simply cannot face the truth of their monumental failures and so must continually bastardize our language in a losing—almost comical—attempt to stay one linguistic step ahead of the truth,” wrote Vietnam veteran Michael Murry.

Gerry Abbott, a linguist at the University of Manchester, wrote a paper called Dying and Killing: Euphemisms in Current English. In it, he said “the fact that euphemism is so embedded in our political systems makes it all the more important that we should resist it.”

Murry’s favourite military euphemism is ‘progress.’

“We go on hearing about 14 years of ‘progress’ which, to hear our generals tell it, would vanish in an instant should the United States withdraw its forces and let the locals and their neighbors sort things out,” he wrote of the war in Afghanistan.

“Since when do ‘fragile gains’ equate to ‘progress?’ Who in their right mind would invest rivers of blood and trillions of dollars in ‘fragility?’”

Amen.

Advertisement