Retired Marine gunnery sergeant and combat diver Dan Griego recovers a coin at an undisclosed site off Cape Breton in 2010 as the crew closed out its last licence after the province repealed the Treasure Trove Act. [COURTESY OF JEFF MACKINNON]

He ended up with Jeff MacKinnon, a third-generation treasure hunter, in Nova Scotia, home to more than 10,000 recorded shipwrecks dating back almost four centuries.

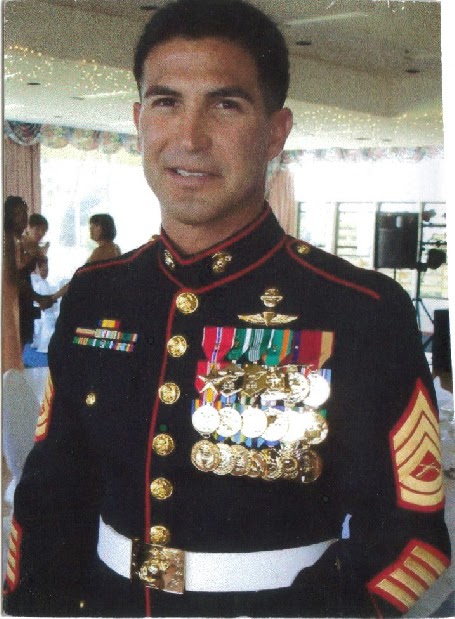

Griego had found the Holy Grail of North American wreck diving, and for two years the highly decorated Marine veteran with nine deployments over two decades mined site after site with an eye to producing a reality television series.

“If you’ve seen the shows that are on today, they’re on Season 8 and still haven’t found anything,” says Griego. “Most of it is just a bunch of BS and editing to make it interesting or scary or whatever.

“I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to go down and actually bring stuff up and it would be about the history and about the people and the experience of doing it.”

His teams of divers, all of them retired police or military from both sides of the border, hit a half-dozen different locations over two years, many of them uncharted debris fields identified by veteran fishermen.

They recovered two cannons, along with some sword pommels and gun parts, all of which they turned over to provincial authorities. There were also coins, which they were free to sell at auction.

For Griego, who has battled demons, served jail time twice and been through rehab twice, it was not about the haul, it was “keeping us out of trouble.”

“Without something to do that is on a large scale like that, where you really have to concentrate and put everything into it, life’s pretty boring,” he said in an interview with Legion Magazine. “That’s what I was looking for, something that we could do as a team again, work together and give something back to them.

“Really, it’s given them life. And then they took it away.”

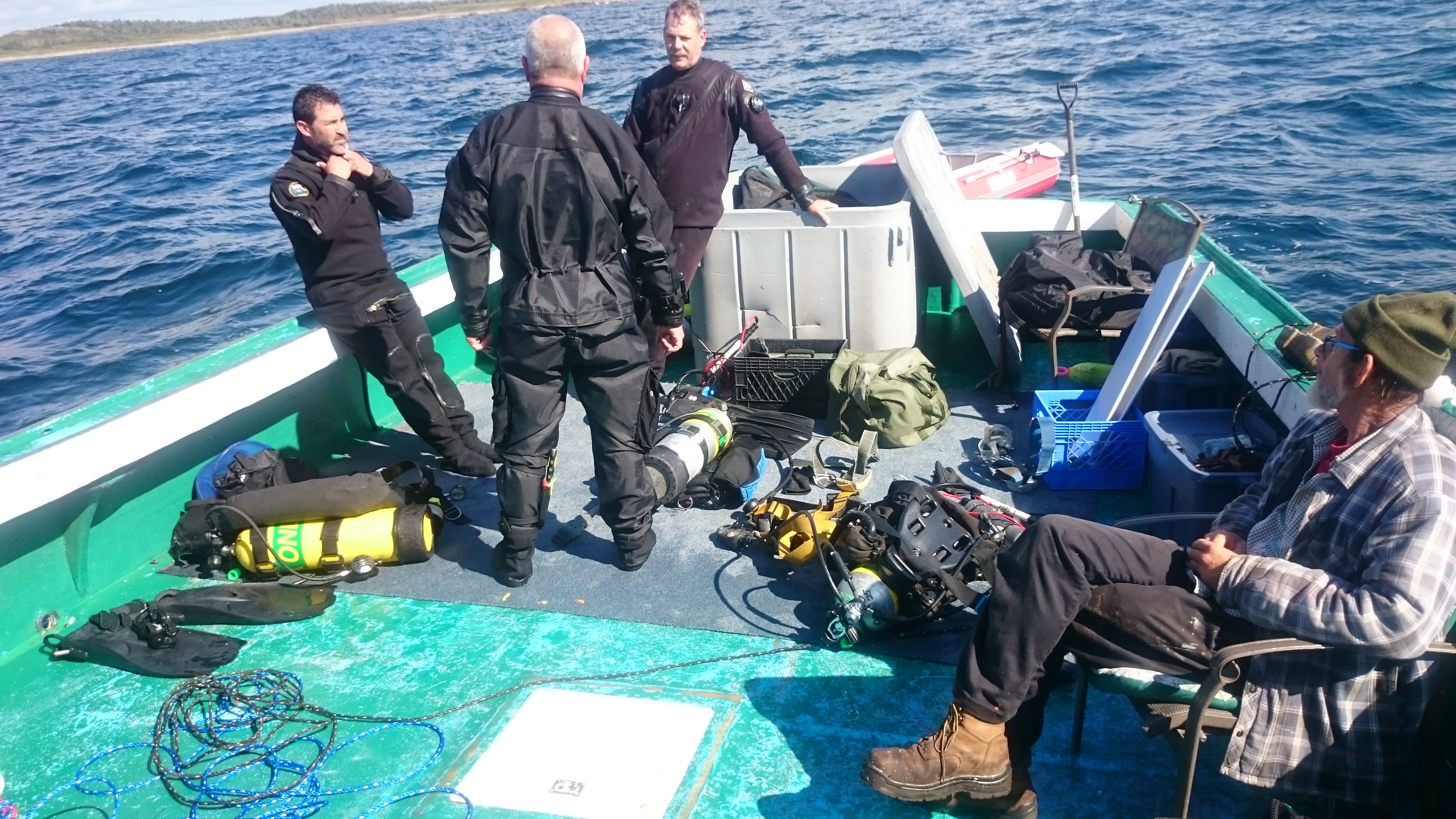

Dan Griego (left), retired FBI detective Mike Pizzio, retired police sergeant Michael Haas and Skipper Timmy do reconnaissance on an undisclosed site off Cape Breton in 2010. [COURTESY OF JEFF MACKINNON]

Unique in North America, the act had allowed licensees to seek and remove treasure found inside designated inshore areas, or territorial waters extending 12 nautical miles from the coast. Treasure hunters were awarded stakes and MacKinnon had his own treasure trove of seasoned fishermen on whom he relied to chart them.

Under the act, “treasure” was considered “precious stones or metals in a state other than their natural state.”

The Treasure Trove Act required licence holders to report any treasures they found, and the minister reserved the right to retain that treasure upon payment of a royalty. In 1965, for example, divers recovered about $500,000 in gold coins and artifacts from Le Chameau, a French pay ship that sank near Louisbourg, N.S., in 1725.

With the repeal, all licences except those awarded on Oak Island expired on Dec. 31, 2010. The move followed complaints that archeological or heritage objects were being treated as a “natural resource with commercial value.”

Delegates at The Royal Canadian Legion convention in Winnipeg passed a resolution last August urging the federal government to formally recognize sunken naval vessels as ocean war graves to protect them from plundering.

MacKinnon, who has launched an effort to reinstate wider-scale licensing, says there were no indications any of the sites their teams excavated were war graves. All the sites were well over a century old and, in most cases, no traces of ships existed.

The only profits to come from his venture, he said, came from the approved sale of coins at auction in the United States.

“Coins are a currency,” said MacKinnon. “There’s no historical benefit to displaying 10,000 of the same type of coin in museums. What it enables us to do is monetize those coins and turn them into a revenue stream that allows us to continue this work.”

The repeal put MacKinnon and Griego out of business and slowed archeological exploration off Nova Scotia to a trickle because, MacKinnon contends, “no government can be expected to conduct these operations.”

“We were spending $30,000 a week just on hotel accommodations,” he said. “You can’t expect the Canadian taxpayer to absorb that kind of a cost. It has to be the private sector and there has to be a return on the investment.”

Cape Breton’s Jeff MacKinnon is a third-generation treasure hunter. [COURTESY OF JEFF MACKINNON]

Shipwrecks are now protected under the province’s Special Places Protection Act. Nova Scotia Communities, Culture and Heritage spokesperson Lynette MacLeod recently told The Canadian Press the province has issued 31 heritage permits with an “underwater/marine component” since 2011.

“In many cases, it is not always practical to collect every artifact from a site and rather than remove objects, archaeological sites are properly documented,” MacLeod said in an e-mail statement.

At its peak, MacKinnon’s operation employed 30 to 40 people, including compressor attendants, boat crews, archeological advisers and 10 divers. Dr. John Whelan, a PTSD specialist in Halifax, was providing counselling services to the veterans and documenting the program’s impacts.

Operating under the working title Treasure Dogz, later to become Operation Recovery, they partnered with Toronto-based Lenz Entertainment and others, filmed a trailer and were offered $350,000 an episode for 13 episodes by an unnamed network.

MacKinnon said the proposal fell through when the legislation was repealed. For the veterans who had staked their hopes on the project, it was a bitter pill.

“We don’t care about bringing the stuff up and keeping it for us,” said Griego, who has a degree in psychology and called the work “the best therapy I ever had.”

“It’s being back in a team again,” he said. “The best therapy is just us hanging around each other and talking and finding that it’s normal to feel the way we do.

“The biggest thing for us is having a mission, putting the guys together and giving them something to do and getting their minds off of themselves, seeing that other people are going through the same stuff. And it’s not just military.”

Retired gunnery sergeant and combat diver Dan Griego in his U.S. Marine dress blues. [COURTESY OF DAN GRIEGO]

Griego says he has seen police, other first responders, even retired professional athletes find purpose in projects like treasure hunting.

“People who were at the top of their profession physically and mentally always want that back—they want to be part of something; they want to have to fight to achieve something, and there are not a lot of things out there like that.”

In 2013, the U.S. Veterans Administration released a study stating that roughly 22 American veterans died by suicide a day, or one every 65 minutes, between 1999 and 2010. Griego says he knows more veterans who died by suicide than in combat.

In Canada, federal authorities have not put a number on the suicide rate among veterans, acknowledging in a report only last year that “based on the information available, it would seem that suicide can be more common among veterans as compared to the Canadian population.”

Eddie Orrell, Progressive Conservative member of the Nova Scotia legislature for the Sydney-area riding of Northside-Westmount, says the treasure-hunting enterprise had great potential for both troubled veterans and the province’s history and heritage.

“We’re losing a lot of heritage and artifacts that are either disappearing because of the shifting of the tides and the ocean or being taken by scavengers,” he said.

“They take that stuff and it’s never reported. We’re losing that part of our history because of the inability of government to enact legislation to keep it from happening.”

The Curse of Oak Island, a popular program on the History Channel, is into its sixth season without having uncovered the treasure supposedly buried there by any number of pirates more than 200 years ago.

The work is authorized by an act specifically governing archeology on the island and Orrell says the show has sparked significant interest among tourists.

The MLA and his Cape Breton colleagues support reinstating some form of the Treasure Trove Act to enable operations like MacKinnon’s to resume operations and perhaps help kick-start a Cape Breton branch of the Halifax-based Maritime Museum of the Atlantic.

Provincial heritage department spokesperson MacLeod told CP the province is “planning to review the Special Places Protection Act as part of Nova Scotia’s Culture Action Plan, including reviewing underwater archaeology.”

Griego said treasure-hunting and wreck-diving were “life-changing” for both him and the others.

“You had something to look forward to the next year. It took me a while to find that. It kept me out of trouble…and guys I knew who were in trouble or suicidal, I could call and say ‘hey, come out here and do this.’ And I did.”

Advertisement