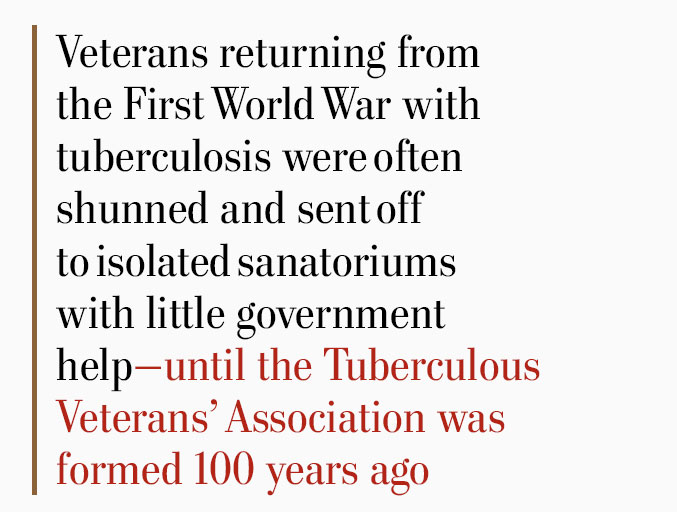

Tuberculous veterans are moved into a sun parlour during the daytime. [Library of Congress/2002646775]

Time spent in the trenches of the First World War was miserable. Not only were chances of being killed or wounded high, but Canadian soldiers were in the line for days at a time in the same damp clothes, fighting over muddy grounds. It was a perfect breeding ground for tuberculosis. Many were infected and brought it home with them.

“At the time, consumption was the number one killer of adults,” said Joanne Henderson of Vancouver, a former national president of The Royal Canadian Legion’s Tuberculous Veterans Section (TVS).

Tuberculosis, often then called consumption, had been a major killer of adults for centuries. Many famous artists such as Frédéric Chopin, Emily Brontë and Robert Louis Stevenson had wasted away with the disease.

At the time, it was believed that the condition was hereditary. It wasn’t until 1882 that German scientist Robert Koch identified the bacterium that causes tuberculosis. With that came the knowledge that tuberculosis was contagious and those infected should be avoided.

Many returning veterans suffering from tuberculosis were sent to the Royal Ottawa Sanatorium. [William James Topley/LAC/PA-009075]

Antibiotics would not be developed until the 1950s. The only cure seemed to be to isolate the patients in sanatoriums, keeping them away from family and society in general. There they lay in beds in wards and were exposed to fresh air and healthy meals.

“There were balconies on the sans,” remembers Jim Crowe of Saskatoon and TVS national president from 1980 to 1984. “As long as it wasn’t more than 20 below, they put you on the balcony, out in the sunshine.”

It was a solitary life, often with few visitors. “You were in bed most of the time. As you got better, you gained certain privileges,” said Crowe.

Treatment of tuberculosis in Canada at the beginning of the 20th century was limited. The first sanatorium in Canada was built in 1897 on Lake Muskoka in Gravenhurst, Ont. Others soon followed in Ontario, Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia. In 1902, the first free tuberculosis hospital in the world, the Muskoka Free Hospital for Consumptives, was built on the same site as the 1897 sanatorium.

By the end of the First World War, an estimated 3,123 soldiers returned to Canada with tuberculosis. While the government built veterans hospitals for the wounded and disabled soldiers returning from the war, the tuberculous veterans were sent to sanatoriums. New wings to existing facilities were built to accommodate the influx.

Unlike the returning amputee veterans, the tuberculous veterans were denied pension and health benefits. This led to the veterans organizing themselves in the sanatoriums.

Veterans in the Tranquille Sanatorium in Kamloops, B.C., were the first to organize, forming the Invalided Tuberculosis Soldiers’ Welfare League (ITSWL). The Tranquille veterans corresponded with veterans in other sanatoriums, building up a nationwide network.

Soldiers were not the only veterans returning with respiratory and lung injuries. Sailors and those who served in the fledgling air services were also vulnerable. So the ITSWL became the Tuberculous Veterans’ Association (TVA) in 1917. It is celebrating its centennial this year.

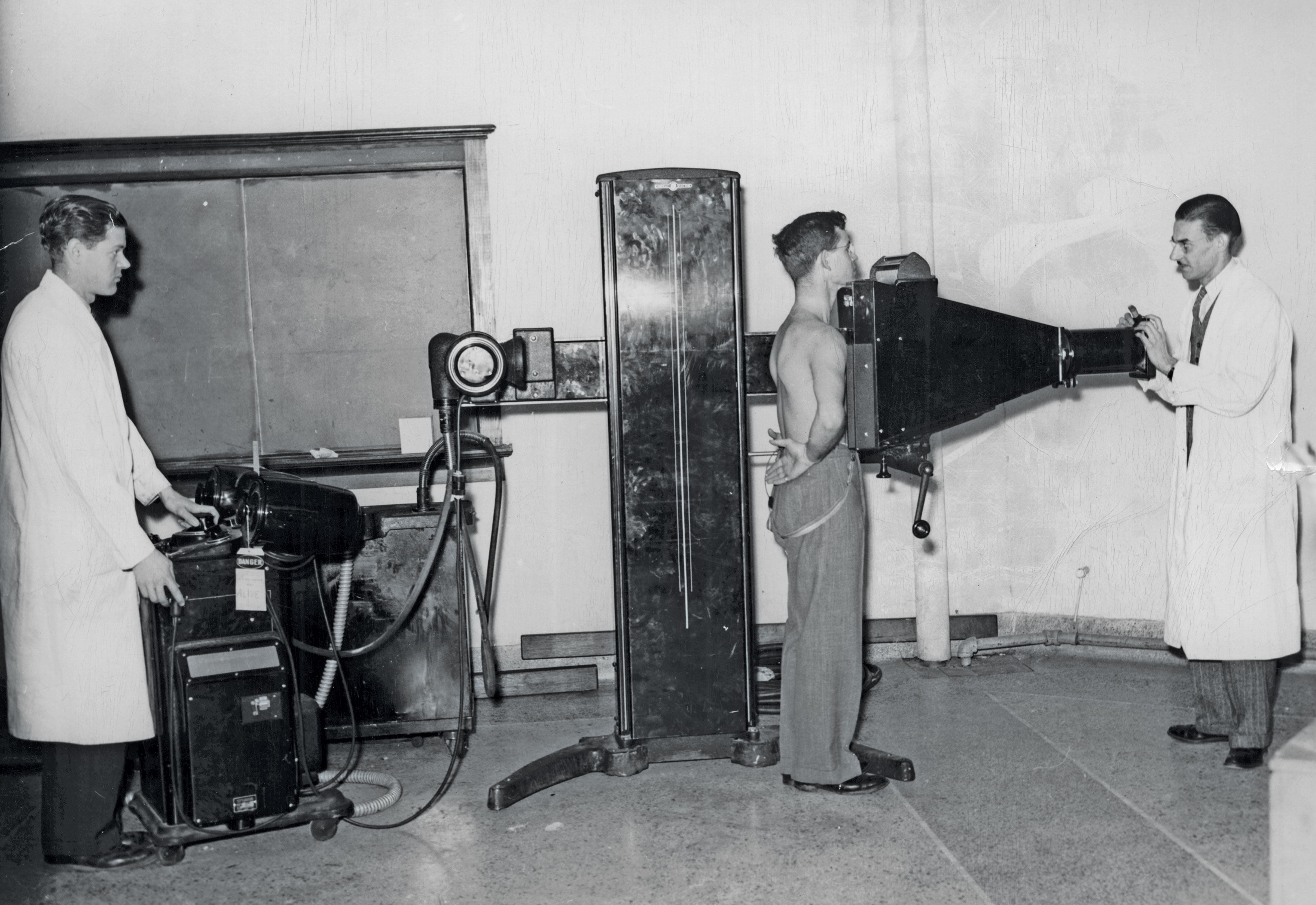

X-rays were used to examine patients for TB. [Archives of Ontario/RG 10-30-2]

As a national organization, the TVA began taking its issues to Parliament. It had approximately 7,000 members and developed a network of service officers across the country to help veterans apply for pensions and other benefits. “These service officers had TB themselves. They were working as volunteers and the money raised was all going into the bank,” said Henderson. “They used their own money to operate. A lot the veterans were prominent people. This happened to them.”

In 1920, the TVA made its first representation to the Parliamentary committee on veteran rights and benefits. The government asked them back the following the year. Through briefings to Parliament and other lobbying efforts, the TVA secured pensions for its members and their survivors. “The big struggle was to get the government to declare TB a federal disease—making the federal government responsible for the health care of those who came back from the war. It wasn’t easy,” said Henderson

The TVA had been singled out in a 1925 report of the royal commission investigating veterans’ benefits headed by veteran and politician James L. Ralston. “No group presented its claim more effectively or thoroughly than the tuberculous veterans,” said the report. “They have, apparently, a large, efficient organization and selected, for purposes of presenting their argument, members fully informed upon the subject which they discussed and capable of presenting their facts in a most convincing manner.”

The TVA was well established by 1926, when Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig came to Canada intent in uniting Canada’s veterans’ organizations into one organization, as he had done in Britain forming the British Empire Service League. The TVA was among the groups courted to join the new Canadian Legion, but because of the special needs of its members, it was not willing to entirely lose its identity. Still its leaders saw the advantage of being part of this larger organization. Instead of disbanding and joining the Legion, it negotiated its own inclusion in the Legion as a special section.

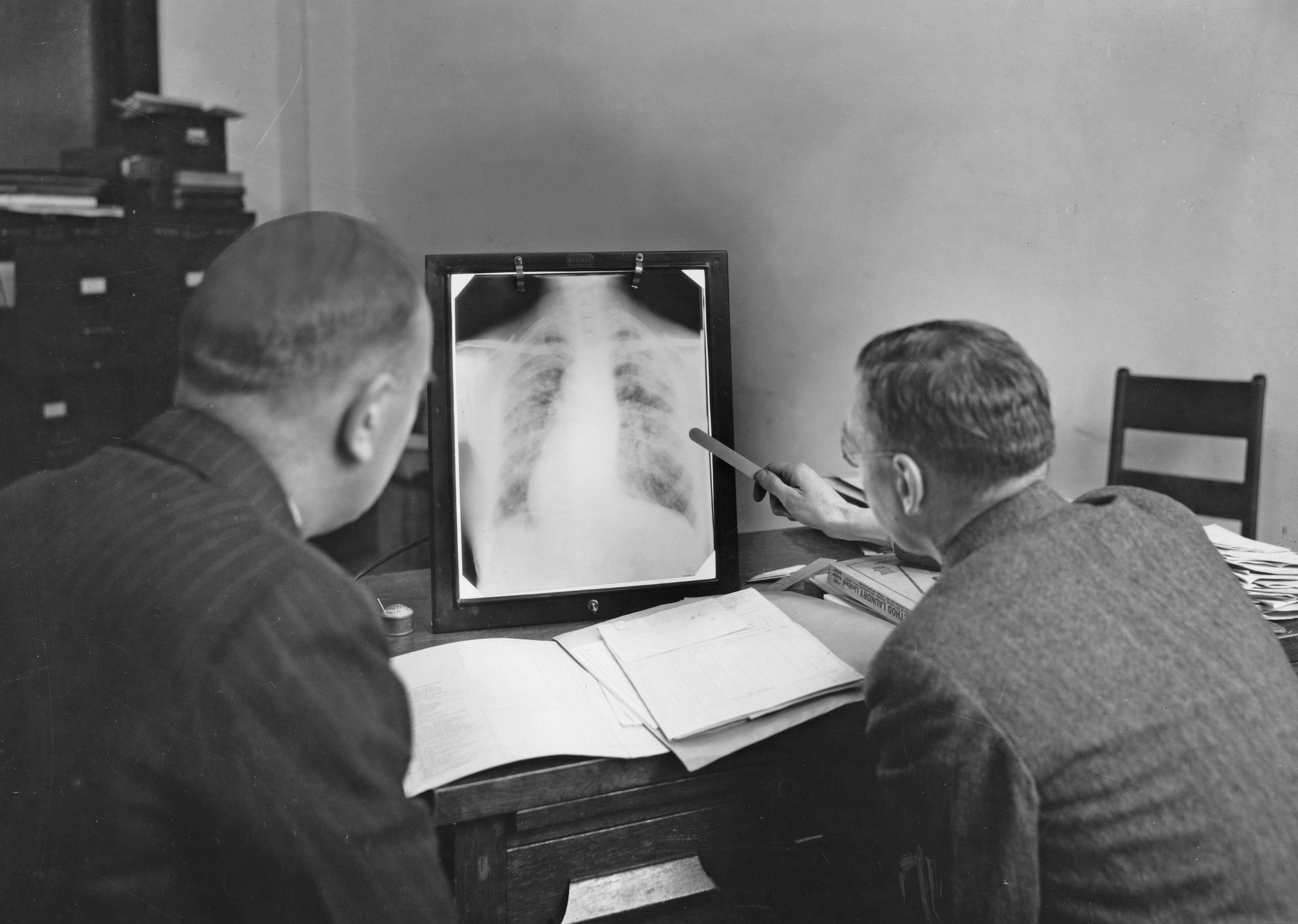

Doctors view a chest X-ray at a Board of Health laboratory in Ontario, circa 1928. [Archives of Ontario/RG 10-30-2]

On Oct. 1, 1926, the association became the Tuberculous Veterans’ Section (TVS) of the Canadian Legion. As Richard Hale, the last dominion president of the TVA, wrote in The Legionary in November 1926, “Many of those comrades who laboured hard for us in the days gone by have gone to their rest. Probably no association has ever carried on under such a handicap as ours has been, and yet what wonderful men we have had, men who sacrificed their chances of recovery in order that our work might go on.”

In order that there be no misunderstanding of the relationship, Hale and others had negotiated with Sir Percy Lake, the first dominion president of the Canadian Legion, on the terms agreed on to create the TVS.

Each provincial executive was to have a TVS representation to be elected by the TVS branch or branches in the province; the Dominion Executive Council would have one representative elected by all the TVS branches. Because of the number of tubercular veterans in Ontario, Toronto and London would retain a service officer.

As well, a duo membership was allowed so that a Legion member could be a member of a TVS branch as well as a regular branch with its own facilities. “There is an incredible bond between those who have TB. People don’t want to touch you. I’ve had people I’ve known for years, see me on the street and turn around and walk the other way. You are removed from human contact and that does a lot to you, mentally.”

Members of the Tuberculous Veterans’ Section meet at the 1946 dominion convention in Quebec City. [TB Vets]

While the largest veterans’ organization joining the Legion was the Great War Veterans Association, in many ways the TVA provided a working model for the organization. It already had a service bureau, which became an important part of Dominion Command.

The TVA also brought $10,000 in its account to the fledgling organization, which was enough to cover operating costs for about three years.

With the end of the Second World War came a new generation of TB-infected veterans. “The soldiers of the Second World War were in the same boat,” said Crowe, who went overseas with the Saskatoon Light Infantry. “There was overcrowding and many of the returning prisoners of war had TB.”

Crowe himself didn’t realize he had returned with tuberculosis. “I didn’t know I was sick. I just knew I was underweight,” he said.

The TVS has continued to support research into TB. In 1944, the antibiotic streptomycin was discovered to be effective in combatting the disease, but it did not become commonly available until 1948. Bacteria resistant to streptomycin soon emerged, so that patients ended up taking it with other drugs to be effective.

“A person with TB is taking at least three or more drugs,” said current TVS National President Kandys Merola. “Once you have TB, you have lung problems the rest of your life.”

That research continues today, said Merola. Much of the research money is raised by TB Vets in British Columbia. TB Vets is a separate organization founded by Vancouver TVS Branch in 1946 to offer employment to Second World War TB veterans who could not find work in the regular workforce.

TB Vets provides key chain tags to help return lost keys to their owners in British Columbia and Yukon.

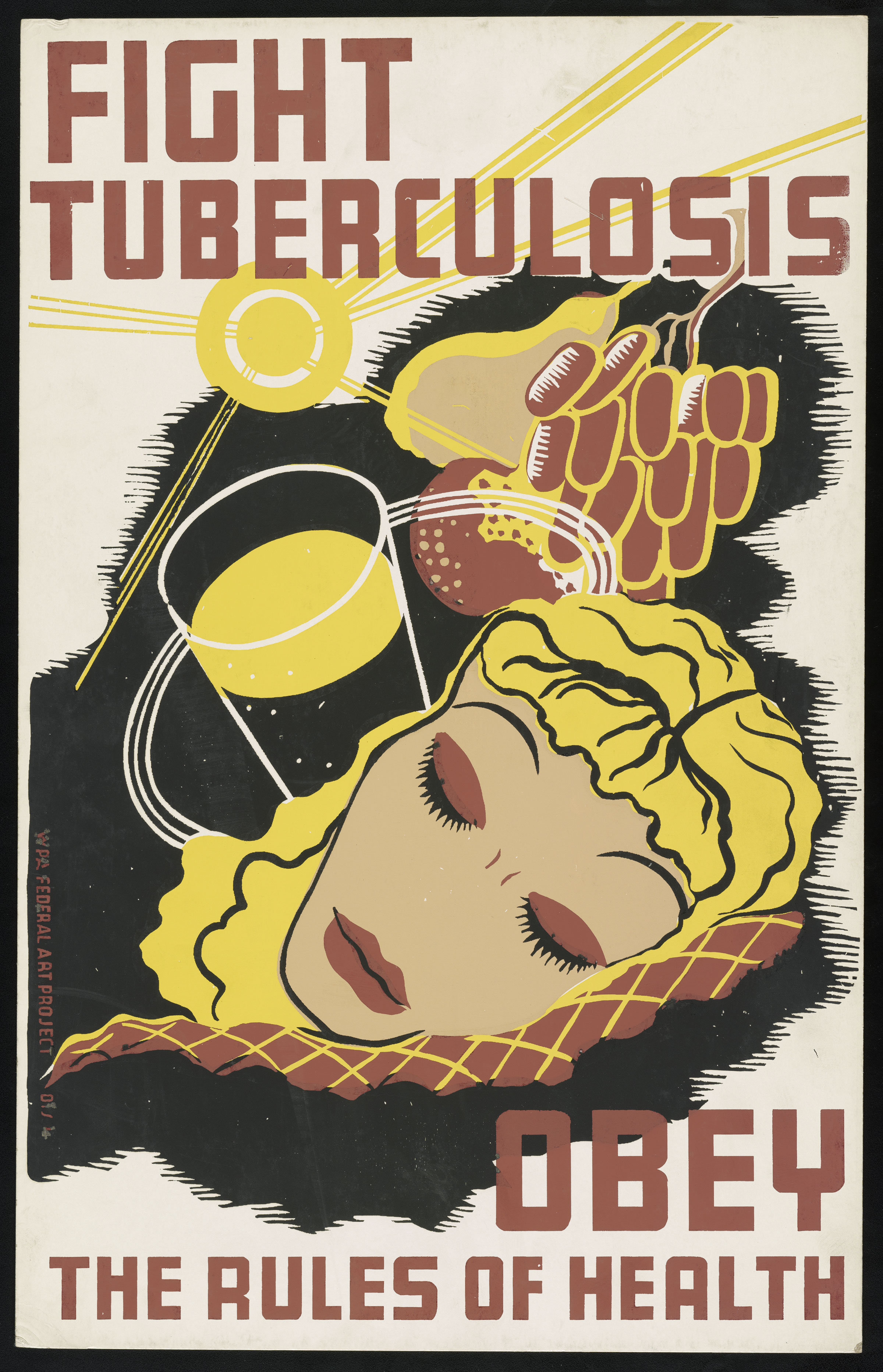

A poster promotes good eating habits and more exposure to sun in an effort to prevent tuberculosis, circa 1941. [Library of Congress/98513584]

Millions of dollars have been spent on research for tuberculosis. In recognition of the longtime support of TB Vets, a ward at the University of British Columbia/Vancouver General Hospital has been named after the organization.

TVS and the Saskatoon Poppy Fund support researchers at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon investigating tuberculosis vaccines in a two-year project.

TVS supports scholarships and the purchase of equipment for medical and nursing students at the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology. Vancouver TVS Branch was also instrumental in reinstituting the Canadian TB Elimination Network, an annual symposium for TB health professionals and stakeholders that had been in limbo after it lost federal-government funding.

Today, the TVS has approximately 480 members in three branches: Vancouver TVS Branch; Hugh Farthing Memorial Branch in Calgary; and Dr. Harold Anderson Memorial Branch in Saskatoon. Like regular Legion branches, TVS branches accept associate members, such as Brent Wignes of Saskatoon who joined because his father was a member. He became national president in 2004 to 2008. “I became a member in 1973, I didn’t go to meetings but Jim [Crowe] would give me things to do,” said Wignes.

One hundred years after the organization’s founding, “There is still a lot of work to be done,” said Wignes. “TB is still quite prevalent in the north with indigenous people. There is always more research to be done.”

Advertisement