The nooks and crannies of my parents’ red-brick house in Halifax held many secrets and, as a child, my insatiable curiosity took me into closets, drawers, attic and basement, most often in search of my father’s past.

Edward Lefferts (Ted) Thorne III was born on Friday, June 13, 1913, and some might say he was cursed. He’d likely tell them otherwise.

He had survived tuberculosis, and lost his mother—a First World War nurse—and brother to the same dreaded disease. He had seen his father lose all in the Depression and his first wife drop dead from a brain hemorrhage. He would lose a daughter to breast cancer.

But in his 90 years on this earth, Dr. Thorne—my dad—delivered hundreds of babies, saved hundreds of lives and, by the time he retired from general practice at 87, he had cultivated hundreds of relationships, mostly good.

He witnessed the rise of the automobile, the airplane, television and the Internet—although he never touched a computer. He watched, spellbound, as America and the USSR embarked on the space race, culminating in Neil Armstrong’s moonwalk.

Yet the central event of my father’s life, the experience that stayed with him until the day he died and changed him perhaps more than any other, was the time he spent as a medical officer in the Royal Canadian Air Force between 1941 and 1946.

He rarely talked about it and, when he did, it was with such nostalgia, deep emotion and soaring reverence for those with whom he served that he sparked my curiosity and captivated my imagination from childhood to this very day.

Those five years were, as Dickens wrote in A Tale of Two Cities, the best of times and the worst, “it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair.”

[Courtesy of Thorne Family; Stephen J. Thorne]

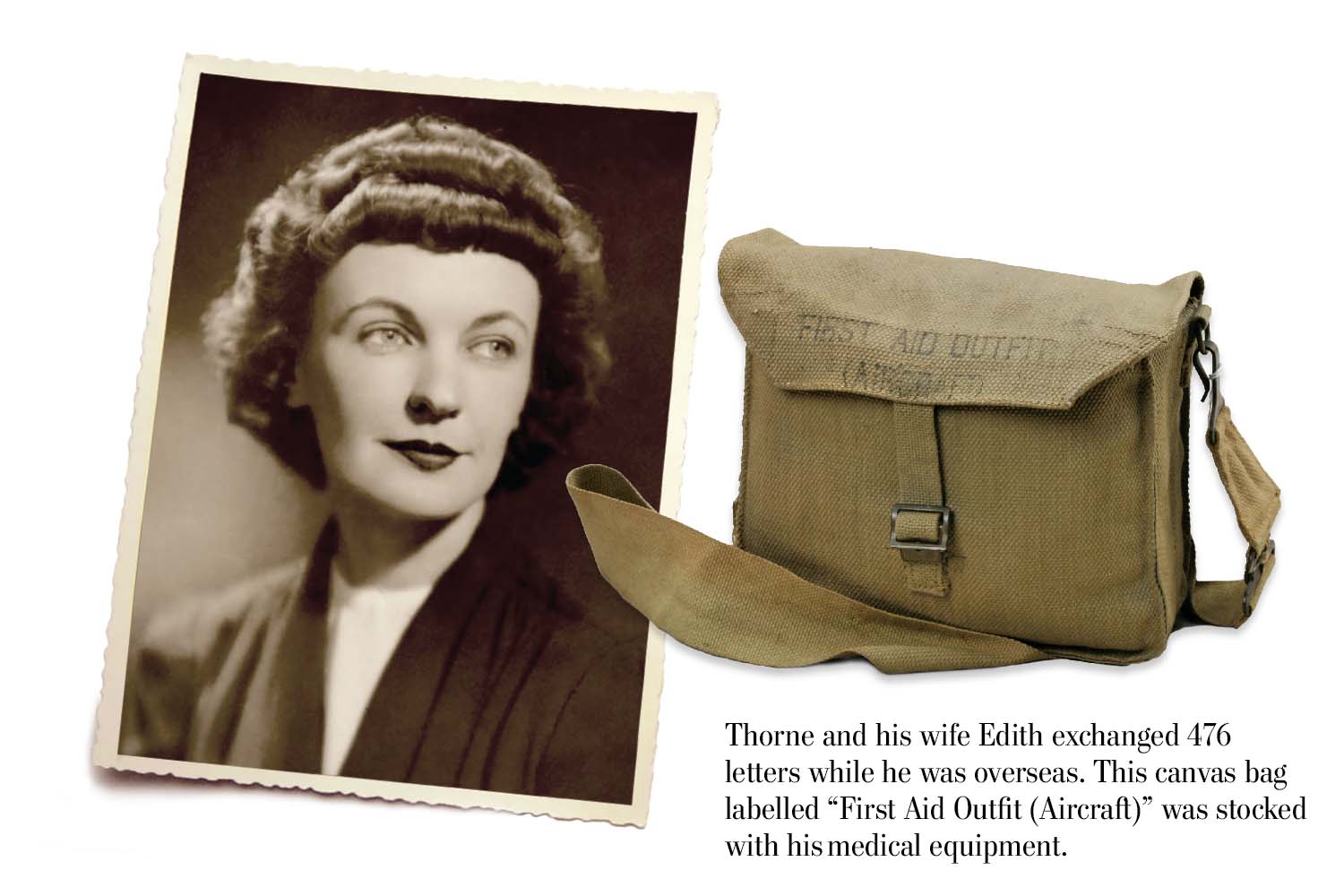

He left my mother Edith as a strapping, youthful air force officer and returned to her 31 months later a broken man who, like so many of his time, had lost friends and seen horrors. But somehow he managed to press on to live a full and productive life despite the demons that haunted him.

His past fascinated me and, as a child, I would crawl into the back of his bedroom closet, find the stacks of shoeboxes filled with letters, mementoes and loose photographs and sit there, behind the hanging clothes, enthralled.

Hanging in a musty basement closet was his flight jacket, with air force caducei on the collar and “June ’44” written inside (he dated everything his whole life—clothes, books, tools). His officer’s hat was propped on an overhead pipe in his workroom. A khaki brown “First Aid Outfit (Aircraft),” still stocked with vials, pills and wraps, hung from a post—not to be touched under any circumstance. (I touched it.)

He kept a photo album in the bottom drawer of his dresser, alongside his service revolver and two knives, their blades and part of their handles fashioned by an aircraftman from the damaged propeller of a Spitfire. The rest of the ringed handles were made of glass taken from Spitfire and Messerschmitt cockpits.

He’d been with two vaunted Spitfire squadrons, 401 and 416, in Scotland and the south of England, as well as 422—a Coastal Command squadron—in Northern Ireland and Bomber Command in northern England.

He was a meticulous man, and on the backs of the hundreds of photographs he took with his Kodak folding camera were detailed notes identifying his subjects, the locations and the dates. Sometimes, there would be additional information.

“R.J. (Paddy) Turp Dec ’42 Redhill, Surrey,” said one, a half-faded shot of a 416 pilot in full kit, his parachute slung haphazardly over his shoulder, oozing the swagger and bravado of the classic air warrior, roguishly grinning through an Errol Flynn moustache. “Shot down with 3 others returning from France, Feby ’43.”

Indeed, Flying Officer Robert Jack Turp of Aurora, Ont., the records show, trained in Summerside, P.E.I., and was killed in action, shot down by FW-190s on an escort mission near Calais on Feb. 3, 1943, the only one of the four to die that day.

There were pictures of a pilot friend, Flt. Lt. Thomas Karl Ibbotson of Radisson, Sask., on his motorcycle. One image showed my dad at 401 Squadron dispersal, Redhill, in June 1943. He’s seated on a bicycle holding onto the roof bracket of a Willy’s jeep.

“Jeep of two Americans attached to us,” it says on the back. “Later ran into Ibbotson on his motor bike and killed him.”

A diary entry dated Aug. 3, 1943, notes “Ibby killed on motor bike on Saturday, Delbridge. Today—sorted his things. Funeral Ibby and Dal at Brookwood at 3 p.m. Abbott and Costello picture, not much.” FO Ralph Balkwill Delbridge from Exeter, Ont., the records show, crashed and died at Underhill Farm, Bucklands, Surrey.

Relations with our American cousins, it seemed, were not always all sweetness and light. On April 21, 1944, my dad noted: “F/O Wright jaw fractured in three places by Americans.” There is at least one other reference to a broken jaw; whether Americans were involved may never be known.

My dad often spoke of “Studholme”—Flt. Lt. Al Studholme, it turned out, a great friend. Dad had fond memories of them hoarding care packages from home and getting together periodically, combining their takes and feasting.

His diaries—there are two, covering 1943 and 1944-45—make numerous references to “cribbage with Stud.” There’s a picture in his album of “Bill Tew and Erks looking at a flak hole in Stud’s wing; flak from a train in France. 401-126 AF, Oct ’43.”

Studholme was lucky that day. It missed his ammunition bay by inches. His luck, however, wouldn’t last. Or would, depending on how you look at it.

One day, Studholme and his wingman, Flt. Lt. Harry Deane Macdonald of Toronto, headed off in their brand-new Spits to link up with a B-17 mission returning from Germany. They never came back. My dad noted on Nov. 30, 1943: “MacDonald lost. Studholme?”

A couple of weeks later, on Dec. 11, 1943, he “wrote Mrs. Studholme.”

He never knew what happened to his friend. At least, he didn’t remember. On Jan. 21, 1944, however, his diary recorded a “letter from Mrs. Studholme. Al p of w.”

A half-century later, I was covering the last reunion of Canadian PoWs for The Canadian Press in Halifax. I ran into a pilot from 401 Squadron. He didn’t know my dad but he knew guys who did, including Al Studholme, who was living in Toronto.

I looked up my father’s old friend and called him, eventually linking him to my dad over the phone and recording their conversation as the wartime buddies caught up on 50 years of life.

My dad’s first question: What happened???

Studholme said he and his wingman reached the German border. Fuel capacity at the time allowed fighters to go no farther. They could see the bombers coming when both their engines inexplicably quit.

Macdonald, Studholme said, turned out to sea and was never seen again (see sidebar on page 47). Studholme got his engine restarted, only to have it quit again. He bailed out and was captured, spending the rest of the war in a German Stalag.

The two old men—both would have been in their 80s at the time—spoke warmly for a while and that was it. For all his fond memories, Dad never attended reunions nor, as far as I could tell, did he maintain ties with any wartime mates.

His role as medical officer put him in a difficult position with some pilots. He sometimes had to ground a man, never a popular decision. He told of a disagreement he’d had with one commanding officer over a pilot who was showing signs of mental distress. My dad wanted to ground the guy, at least temporarily. His CO refused it, saying his pilot would be fine. A few days later, that pilot got in his Spit and flew it into the sea.

Still, the pilots of the RCAF overseas had much to be thankful for in Flt. Lt. E.L. Thorne. His bedside manner was impeccable—warm, receptive, charming. Being sick in the Thorne household was one of the few times he diverted from his medical practice and gave his children his undivided attention and tender, loving care.

No doubt, the pilots he nurtured felt a similar bedside manner. His diaries reference daily sick parades, inoculating 300 air force personnel against typhus in one day, and collecting dead and wounded aircrew from the English countryside.

On Nov. 22, 1944, he was “up 12:30-5 a.m., to pick up parachutist with broken foot, crawled 3 mi.” On Jan. 17, 1945: “Crash 9 bodies.”

He talked of using tweezers to pick dozens of pieces of shrapnel out of a pilot’s back. I still wear the Movado watch given to him by an American pilot out of gratitude for his care. “A thoroughly competent medical officer, very well liked by all personnel in the squadron,” Wing Commander L.P. McCullagh wrote in 1944.

His diaries tell of kites, prangs, Jerries, dos and rhubarbs. There are trips to the theatre, books he read, bombing raids and endless parties. Jan. 14, 1943: “Jackie Ray’s wedding. Two accidents. Big party.” The following day: “Quiet recovery.”

This was, in fact, Jackie Rae, politician Bob Rae’s uncle and a renowned Canadian entertainer. He married Assistant Section Officer Susanna Mitchell of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force. Squadron Leader Lloyd Chadburn, the Canadian ace known to my dad and American bomber crews as “The Angel,” was groomsman. It would not be Jackie Rae’s last wedding, and Chadburn would die in a mid-air collision with another Spit over France on Dad’s 31st birthday, one week after D-Day.

His diaries recorded victories (July 6, 1943: “Sweep over St-Omer. Score 8-0!”) and defeats (Jan. 29, 1944: “Crashed Fort and Lib. 1 dead at 3 p.m.). On Jan. 24, 1944: “Shep bailed out. Picked up in 40 minutes by launch 10 mi off Boulogne Harb at noon.”

My dad spoke bitterly of an incident in which Germans bombed a theatre full of kids. A plane was shot down and my dad was sent to collect the dead, retrieving the pilot’s pelvis from a treetop. He references the incident on July 9, 1943: “Felt awful. Dornier 2[17] crashed near Bletchley after bombing theatre.”

Entries in my father’s diaries were often punctuated with a number—145, 103, etc. They were counting the letters to and from my mom. On D-Day, June 6, 1944: “D-Day! At Castle Archdale. 144 and 147 from Edith. 176.”

Her letters generally took a month to reach him. In the two years the diaries covered, he wrote her 273 letters and received 203. She also sent him care packages, often with cigarettes. He sent her cables. And gifts. In the back of one diary is a touching list of my mother’s 28-year-old measurements and sizes: 5’2”; Size 6AA shoes; hand 6”; head 221/2, etc.

Castle Archdale was in Northern Ireland, home to 422 and 423 Squadrons. It sounded like the end of the Earth—a cold, barren, windswept place. Posted there in March 1944, my father had a fireplace in his room and waged constant war with mice, who kept him up at night. He got traps and kept a tally: 21 at last count.

The day he arrived at the castle, on March 10, 1944, he spent 34 shillings on taxis and tips and noted that “422 got sub tonight.”

This was U-625, sunk with all 53 hands west of Ireland by depth charges from a Sunderland flown by Flt. Lt. Sydney William Butler, DFC. The U-boat captain, Oberleutnant zur See Siegfried Straub, and many of his crew made it to life rafts but were lost in a storm the following night.

On April 24, 1944: “423 kite attacked sub this afternoon—probable. Pretty badly shot up, nobody injured.” The records show an attack on U-672, skippered by Oblt. Ulf Lawaetz. The Sunderland flown by Flt. Lt. G. Fellows launched the attack southwest of Ireland at 1:39 p.m. The U-boat was severely damaged, and so was the aircraft after a depth charge detonated prematurely, almost bringing it down.

According to 423’s Operations Record Book, “the force of this explosion was such as to throw up the entire moveable contents of the aircraft—floorboards, I.F.F. [Identify Friend/Foe] set, crockery, eggs and oven, forming a new variety of omelet.”

It knocked out electrical circuits, severed cables, opened wing seams and disabled the port flaps. “But the principal damage was to the elevator which needed all the skill and strength of the Captain assisted by the Second Pilot to counteract.”

The crew were moved forward of the main spar to help maintain trim. Still, they stayed on-station for 36 minutes after the attack.

As Allied forces approached Rome, my father noted that six aircrews out of Castle Archdale were patrolling the Norwegian coast. Just three in 20 U-boats were getting out undetected.

He moved on to Bomber Command in northern England, from which he recounted the tale of a fresh young recruit who took the tail-gun position of a B-17 the morning after he arrived, only to return ankle-deep in shell casings and needing help to peel his fingers from his .50-calibre machine gun.

One of Dad’s last diary entries came on Feb. 15, 1945: “Collected body RM Ward. Any day now. Walked with Orp and packed.”

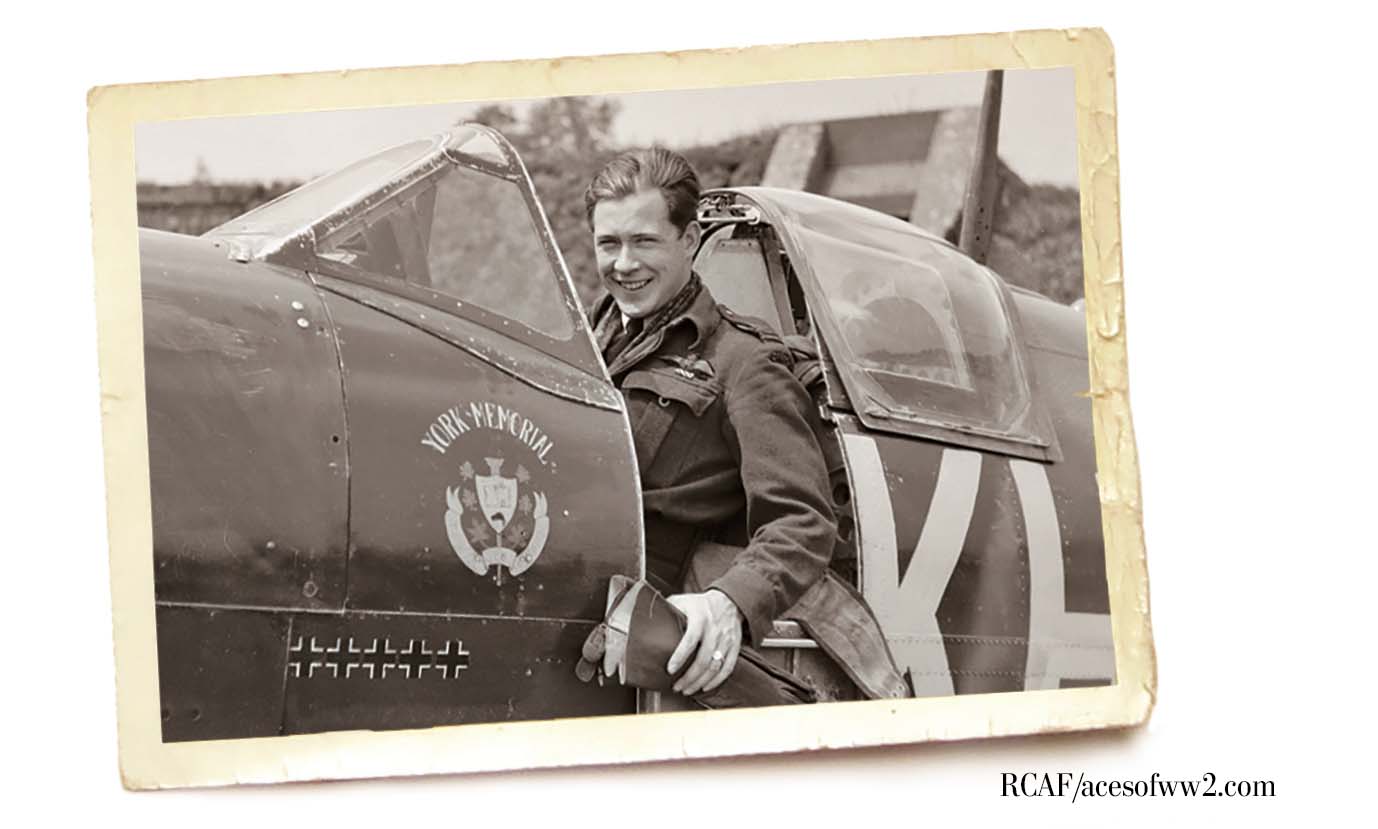

The hole in this Spitfire’s wing was caused by “flak from a train in France.” The aircraft was piloted by 401 Squadron’s Flt. Lt. Al Studholme, one of Thorne’s best friends during the war. [Flt. Lt. E.L. Thorne/CWM]

My father left the air force in 1946 and was in and out of the army and air force reserve for the next two decades, finally retiring from military duty a major in 1968. He spent his postwar life in the endless pursuit of learning. He read constantly. He researched developments in medicine, tinkered with his beloved cars, experimented in carpentry and mechanics, listened to symphonies and operas on the radio.

Somewhat eccentric, he was a collector of things, born of the Depression-era mentality that everything must be saved, from corks and string to elastic bands and twist ties. He kept jars full of salvaged nails, screws, nuts and bolts. He was into recycling before recycling was even a thing.

Rationing was a way of life in our household. Occasionally, my dad would break out a banana and a box of Baker’s brand semi-sweet dark chocolate. He would cut a few squares and present me with two, sometimes three, insisting I take a bite of banana with each bite of chocolate.

One September day in 1998, I was heading back to The Canadian Press office in Halifax after spending nearly 24 hours at the scene of the Swissair Flight 111 crash off Peggy’s Cove, N.S. I was driving past my dad’s office when I saw him crossing the street. I pulled over, opened the passenger-side window, and told him I’d spent the day aboard a small fishing boat out on the water, at the crash site.

I didn’t need to tell him what we found there. He knew. He nodded, pursed his lips and studied my face: “I know, son,” he said. “I know where you’ve been.” There was a silence and then I headed off.

It was probably the most poignant moment we’d ever had. I returned to the newsroom and wrote the words: “The lives of the 229 passengers and crew who died aboard Swissair Flight 111 float by in 100,000 tiny pieces.”

My life would never be the same again.

In his book Lucky 13, Hugh Godefroy, another colleague of my dad’s, had the answer to what happened to Flight Lieutenant Harry Deane Macdonald, DFC with bar, who was lost while flying to link up with a B-17 mission returning from Germany after the Spitfire he was flying lost engine power:

“Two of his squadron flew with him while he glided back,” wrote Godefroy. They were in heavy cloud before coming out 1,500 feet above the water. “Dean tried to bail by pushing the stick forward to throw himself out over the top. The two fellows who were with him said he landed astride the aircraft, impaled on the radio mast and rode it into the sea.” —S.J.T.

Advertisement