Canada was formed by a combination of hope and fear; hope that something great could be created in the wilderness, and fear of American imperialism and Fenian raiders. At 150, we are no longer young, but compared to our aging parents (England is 1,146 years old, if you count Alfred the Great as its first king, France a creaky 1,531), we remain youthful. When we look back at our shared mythologies—the people, politics and events that made Canada, we see heroism, occasional chaos and the overcoming of long odds, starting with Confederation.

Confederation brought together four men who were divided by religious, political, linguistic and regional animosities. John A. Macdonald dominated Upper Canadian politics, a Conservative Scot who distrusted the English and was often drunk. George Brown was the Liberal publisher of The Globe, a sober Presbyterian and one of Macdonald’s harshest critics. When he criticized Macdonald’s drinking, Macdonald responded that most voters “would rather have a drunken John A. Macdonald than a sober George Brown.” Which turned out to be true. George-Étienne Cartier was Lower Canada’s most eloquent politician and had fought the British in the 1837 Rebellion—Brown referred to him as “that damnable little French Canadian.” Thomas D’Arcy McGee was an Irish Catholic who once described himself as a “Traitor to the British Government.”

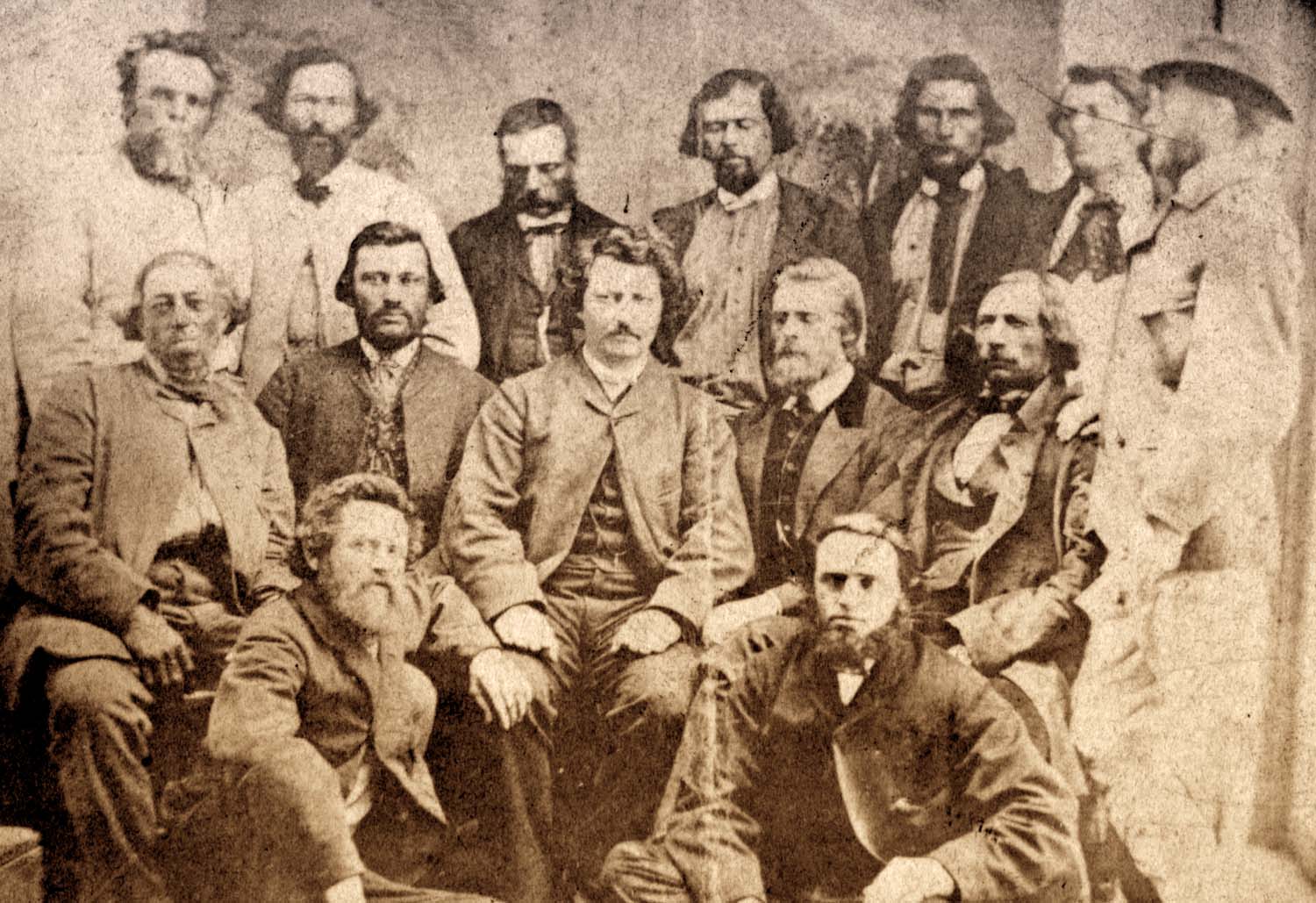

Delegates from Canada, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island met in Charlottetown to discuss Confederation in September 1864. [LAC/C000733]

These unlikely allies arrived in Charlottetown in September 1864 to convince the Atlantic colonies to join their bold plan of creating a country. They were armed with their considerable eloquence and $13,000 worth of champagne. After a week of speeches, the party moved to Quebec and weeks of negotiation, bullying and drinking. By the end of the process, a constitution was drafted, most of it by Macdonald. The idea was sold to the people in the colonies using the fear of Fenian raiders and an imperialist America; if they didn’t unite, they would be overtaken by some foreign evil. On March 29, 1867, Queen Victoria signed the British North America Act, and on July 1 the Dominion of Canada was born.

The early reviews were mixed. In Halifax, the British Colonist celebrated the union. “The days of isolation and dwarf-hood are past; henceforth we are a united people, and the greatness of each goes to swell the greatness of the whole.” The Morning Chronicle was less thrilled. “Died! Last night at 12 o’clock, the free and enlightened Province of Nova Scotia.” An effigy of Charles Tupper, the Nova Scotia premier who had supported Confederation, was burned on the waterfront, along with a live rat.

D’Arcy McGee eloquently defended Tupper in what would be his last speech in the House of Commons. When he walked home at 1 a.m., he was followed by a suspected Fenian named Patrick James Whelan. When McGee reached the boarding house of one Mrs. Trotter, where he was staying, Whelan shot him in the head, killing him instantly.

Ships from the Hudson’s Bay Company anchored in Hudson Strait in 1819 to barter with Inuit for blubber and bladders of oil. [D. Hurley/LAC/C-015369]

The country was born in tentative alliances, persistent hangovers, negotiation and blood. So, a difficult birth.

But countries aren’t really born. They evolve; borders shift, populations grow and become more diverse. Power changes hands, shaping the nation. Countries aren’t static.

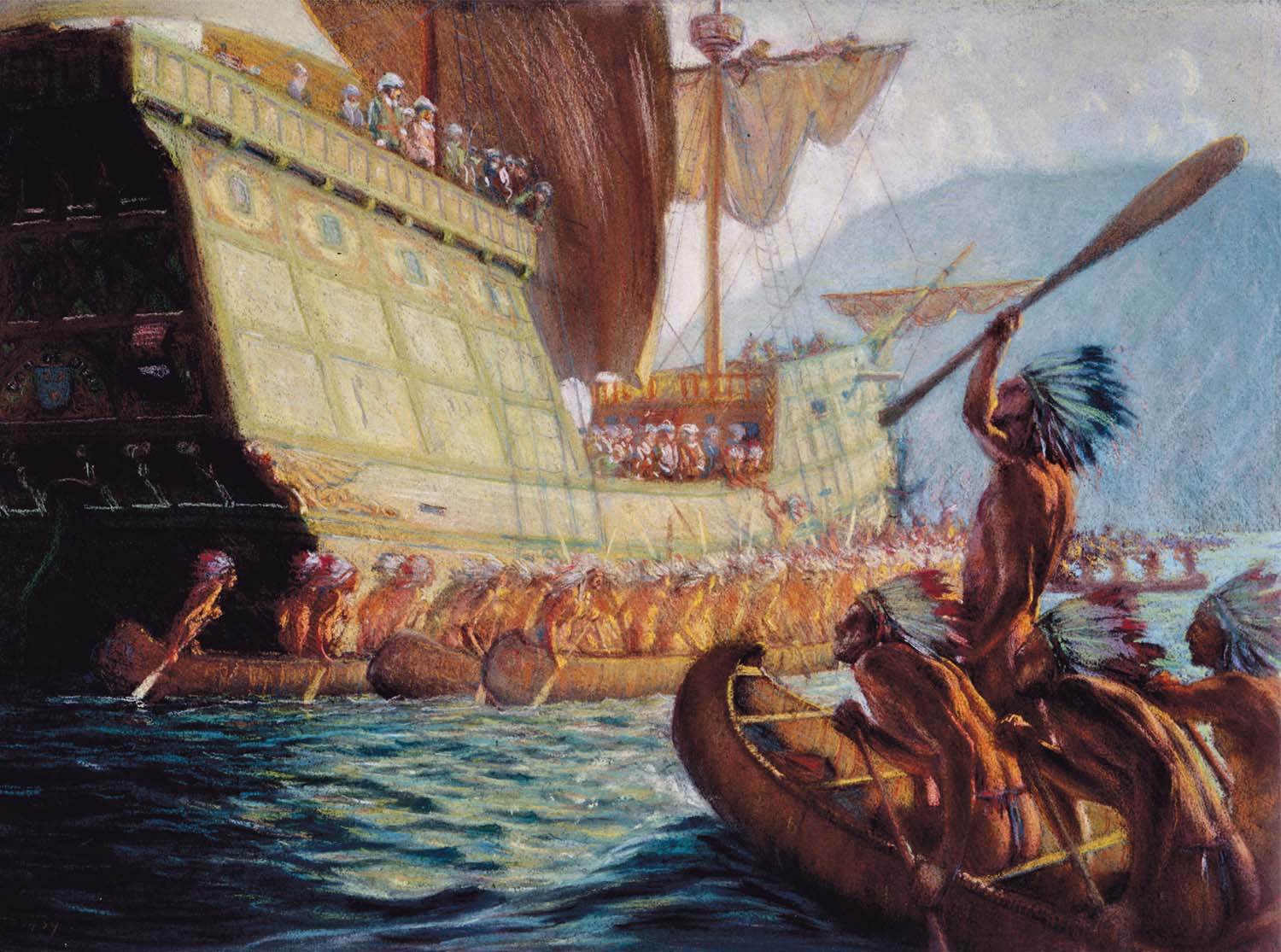

The country that was proclaimed in 1867 had always existed in some form. The aboriginal peoples had been here for thousands of years. Leif Erikson visited briefly around 1000 AD. Five centuries later, the Europeans began to arrive in earnest—John Cabot, Jacques Cartier, Humphrey Gilbert, Martin Frobisher. They all held a different version of what Canada was (China, a source of gold, a route to India), though it would be years before anyone considered what it could be.

Initially, the land offered little more than resources, specifically beaver pelts. The beaver hat was all the rage in Europe because of its strength and malleability, and this created a thriving fur trade. In the 1840s however, Prince Albert, consort to Queen Victoria, began wearing a silk hat, which started a new trend. Silk was cheaper and became more stylish, and the beaver hat fashion died, as all fashions do.

Hats of felted beaver fur were de rigueur among the fashionable, including these gentlemen in Boise City, Idaho, in 1886. [R. Hood/LAC/C-040364]

But the fur trade did more than enrich a handful of investors; it led to the exploration and mapping of the West. Its greatest cartographer was David Thompson, who worked for both the Hudson’s Bay Company and later, its rival, the North West Company. During his life, he walked and canoed more than 80,000 kilometres, mapping not just the land, but the flora and fauna, as well as the languages and customs of the First Nations. He married a Métis woman, Charlotte Small, and she and their children often accompanied Thompson on his travels. He was called “the greatest land geographer who ever lived,” and like many geniuses, he died in poverty and obscurity.

The West was owned by the Hudson’s Bay Company, and in 1869—under pressure from Great Britain which feared the United States would try to claim it—the company reluctantly sold the vast territory to Canada for $1.5 million. No thought had been given to the inhabitants.

“No explanation it appears has been made of the arrangement by which the country is to be handed over,” Macdonald told Cartier. “All those poor people know is that Canada has bought the country from the Hudson’s Bay Company and that they are handed over like a flock of sheep to us.”

They weren’t sheep. Western First Nations had seen their numbers decrease due to smallpox, whisky and the ongoing decimation of the buffalo, but they were still numerous and a potential military threat. To the south, the U.S. government was fighting vicious wars with the native Americans, and Macdonald hoped to avoid similar bloodshed in Canada. He was worried that some of them might join the Métis leader Louis Riel and there could be war.

Two of the strongest Plains Indian chiefs, Big Bear, leader of the Cree, and Crowfoot, representing the Blackfoot, had gone south to Montana, chasing the last of the buffalo. There they found Riel, who had been teaching school near Fort Carrol since his release from a mental asylum in Beauport, Que., in 1878. Riel tried to convince them to join his planned rebellion, telling them the government wouldn’t honour the treaties. This turned out to be true, although neither chief joined Riel.

The provisional government of the Métis Nation convened in Manitoba in 1870. Louis Riel is in the centre row, third from left. [LAC/PA-012854]

Others did, however. When Riel returned to Canada, it was like Moses coming down from the mountain, and he did exhibit flashes of the religious mania that had driven him to the asylum. He also had a legitimate grievance and a receptive audience. John A. Macdonald, who was something of an expert on charisma, was wary of Riel’s and what it could lead to.

Macdonald had been having trouble raising the money and support he needed for his idea of a transcontinental railway. Faced with two crises, he used one to solve the other. The railway was necessary, he argued, to get troops to the West to put down Riel’s simmering rebellion.

When the rebellion was quelled and Riel captured, there was political pressure from English Canada to hang him for treason. At the time, treason wasn’t a hanging offence, so Macdonald and his justice minister invoked a British law from 1342 and charged him with high treason, which did carry the death penalty. The trial was a travesty, a foregone conclusion, and Riel was hanged. He became a martyr, and further divided the country, pitting First Nations and Métis against the government, Protestants against Catholics, and French Canada against English.

Crowfoot, chief of the Siksika First Nation, addressed Governor General John Campbell during a powwow at Blackfoot Crossing on the Bow River in 1881. [S.P. Hall/LAC/C-121918]

But Macdonald got his railroad, that symbol of unity and perseverance. In 1886, he boarded the first transcontinental train, and in the Alberta foothills he met with Crowfoot, who told him, “My chiefs fear for their children, that food would not be given them. I ask you Sir John to help banish these fears.” The Plains people had seen the treaty promises unfulfilled and many of them starved. Macdonald gave Crowfoot a new suit, and William Van Horne gave him a lifetime pass for the CPR. Some of Crowfoot’s children did in fact starve. Of his 12 children, only four made it to adulthood, then they succumbed to tuberculosis or starvation. In 1890, Crowfoot himself lay dying of tuberculosis in a tent near Gleichen, Alta. Among those present was his mother, almost 100 years old, witness to all the dismal changes the century had brought to her people.

Little more than a year later, Macdonald died. Intemperate, energetic, articulate and endlessly political, Macdonald personified the new country in many of its graces and some of its sins. He saw the demise of a native way of life and vanquished his enemy Riel, but more than a century later, those ghosts remain vivid and potent.

Lord Donald A. Smith hammered the last spike to complete the Canadian Pacific Railway near Craigellachie, B.C., on Nov. 7, 1885. [LAC/C-003693;]

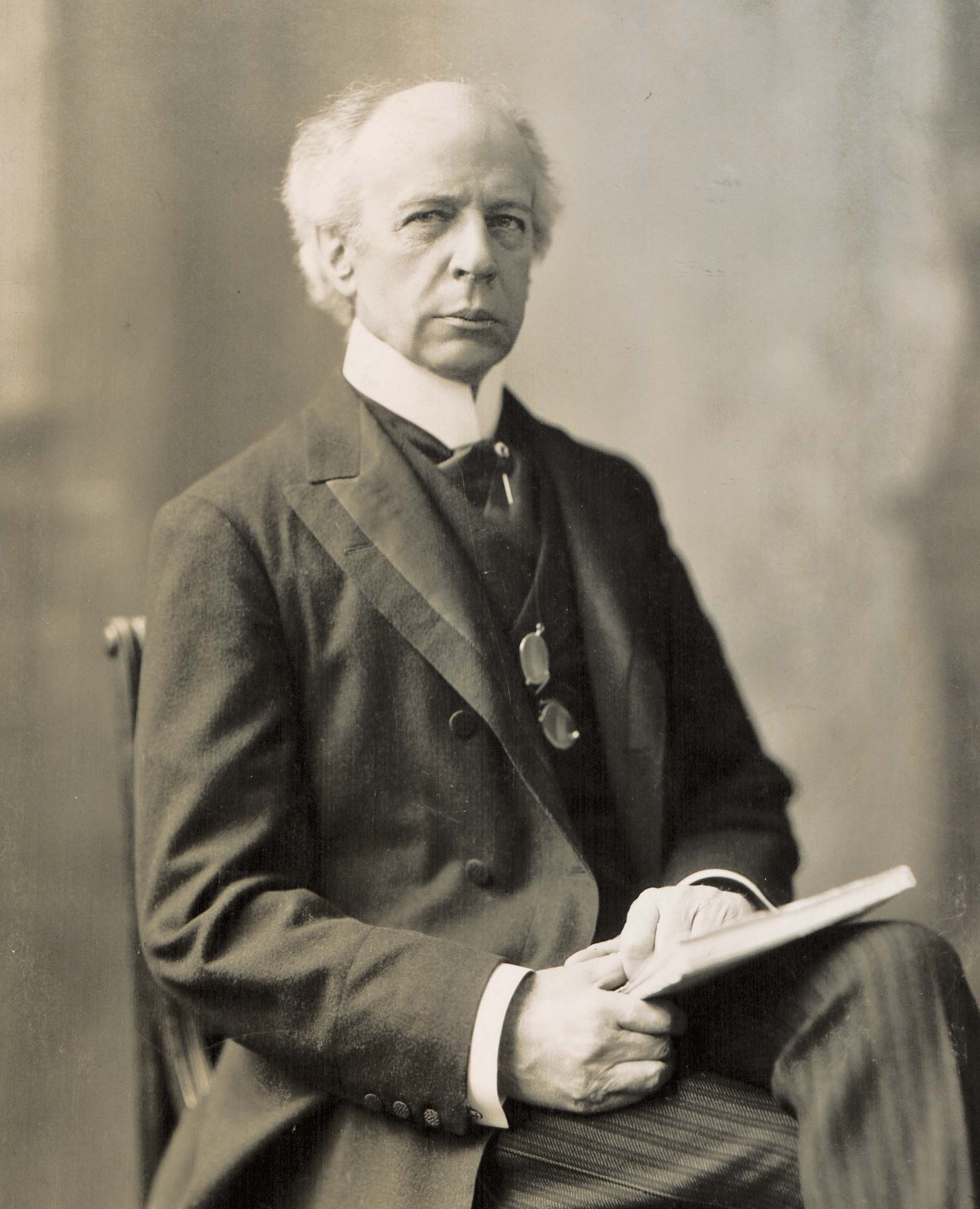

Now the country was bound by the railway, but there was still the problem of populating the Prairies. This Herculean task fell to Clifford Sifton, Minister of the Interior under Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier. It was Laurier who announced in 1904 that “the twentieth century shall be the century of Canada.” His prediction was off by a hundred years, but his optimism was contagious. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s “sunny ways” philosophy of governing was taken from Laurier, who coined the phrase.

Sir Wilfrid Laurier was Canada’s first francophone prime minister. [LAC/C-000688]

Laurier was the first francophone prime minister, a man of tremendous charm and political skill. The country’s linguistic divide narrowed slightly under his leadership; some anglophones thought him too French, while certain francophones felt he was too British—a perfect balance for Canada’s linguistic complexities.

The Japanese steamship Komagata Maru carried 376 Indian passengers with hopes of immigrating to Canada in 1914. Twenty-four were admitted, but 352 were forced to return to India under Canadian exclusion laws. [LAC/PA-034015]

Canada had abundant natural resources, but it needed people to exploit them. Given the challenge of bringing immigrants to farm the Prairies, Sifton first tried to attract British and Americans. When they weren’t enough, he widened the search to include Poles, Finns, Icelanders and Ukrainians. He sent agents to Europe to spread the word, offered free land and distributed more than a million pamphlets extolling the virtues of the Canadian West. The pamphlets were poetic (“building Jerusalem in this pleasant land”) and often misleading (“the frontier of Manitoba is about the same latitude as Paris”), but they were effective. During Sifton’s tenure, the population of the West went from 300,000 to 1.5 million. This policy of aggressively courting immigrants ended abruptly in 1914 when 352 immigrants from Punjab, British India, aboard the Komagata Maru were turned away from Vancouver harbour. The country—and much of the world—was mired in an economic depression, and our largesse was at an end.

In Europe, a greater danger loomed. On June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria was assassinated by a Serbian nationalist in Sarajevo. As a result, Austria declared war on Serbia, Russia mobilized, and Germany declared war on Russia and France. Germany invaded neutral Belgium, which drew Britain into the mess; on August 4, it too was at war.

As a colony, we were automatically at war when Britain was. Tens of thousands enlisted, the majority of them British-born Canadians. There remained a romantic view of war. One of the people who had a prescient view of what was coming was John McCrae, who wrote to a friend, “It will be a terrible war.” McCrae had seen the carnage and inhumanity of the Boer War, and expected worse for this one. He would be proved right.

Canadian soldiers trained with gas masks known as PH helmets (for phenate and hexamine) at Shorncliffe Army Camp in Kent, England, in 1917. [DND/LAC/PA-001270]

On April 22, 1915, it was clear that this war wouldn’t be like those that had preceded it. At Ypres in Belgium, a heavy cloud of chlorine gas invaded the Allied trenches; the age of chemical warfare had begun. The battle resulted in more than 6,000 Canadian casualties. It was here McCrae wrote “In Flanders Fields.”

“The general impression in my mind is of a nightmare,” McCrae wrote to his mother. “We have been in the most bitter of fights…gunfire and rifle fire never ceased for 60 seconds.… And behind it all was the constant background of the sights of the dead, the wounded, the maimed, and a terrible anxiety lest the line should give way.” McCrae was reassigned to a hospital on the northern coast of France, and this is where he died.

Medical officer John McCrae composed “In Flanders Fields” in 1915. [Wikimedia]

At home, the war drew new divisions. The German and Ukrainian immigrants who had been wooed were now viewed with suspicion. “Enemy aliens” were forced to register, and by the end of the war, there were 80,000 of them. The war intensified, and in 1916 there came the horrors of the Somme. In that five-month battle, the Allies gained 13 kilometres of decimated land, and suffered 623,907 casualties. The Germans lost 660,000 and termed it das Blutbad (the bloodbath). Any remaining sense of romance about war vanished.

A truckload of “Byng Boys”—named for Lieutenant-General Julian Byng, commander of the Canadian Corps in April 1917—returned victorious from Vimy Ridge. [C.M. Johnston/LAC/PA-056171]

The Battle of Vimy Ridge in April 1917 also took a toll (3,598 Canadians killed and 7,004 wounded) but it was seen as a great Canadian victory, the battle that moved Canada away from colonial status toward nationhood. But it wasn’t enough to unite the country on the issue of conscription. Francophones argued that it wasn’t their war, and rural anglophones said they needed their sons to work the farms. Aboriginals were the most willing to fight, oddly, given their history of neglect and oppression; of the 11,000 eligible to fight, a third signed up, a proportion that was twice the national average. When the war ended, on Nov. 11, 1918, there was tremendous relief, but new fault lines had formed in the country.

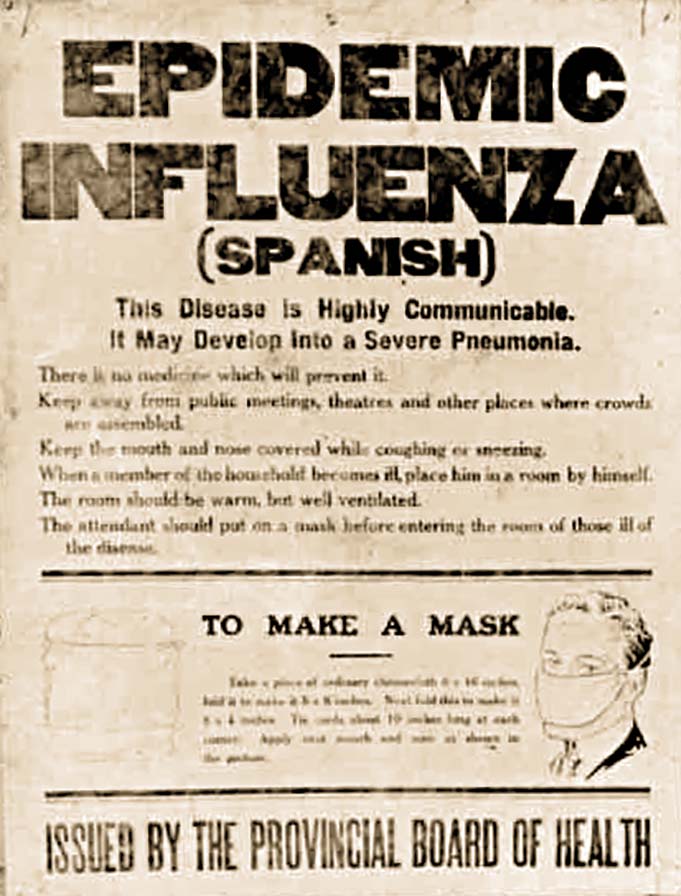

In 1918, Alberta’s Provincial Board of Health issued this poster warning of the influenza epidemic. [LAC/PA-183773]

Thousands of veterans returned home, expecting a reward for their sacrifice. At the very least, they expected jobs. Instead, war factories were shutting down and there was unemployment, inflation and a housing shortage. The unrest resulted in the Winnipeg General Strike in the spring of 1919, which culminated in “Bloody Saturday,” when two strikers were killed in a Winnipeg demonstration. Compounding the homecoming problems was the flu pandemic, which killed more people than the war had.

Strikers overturned a streetcar in front of city hall in the Winnipeg General Strike in 1919. [Winnipeg Free Press]

The 1920s offered relief, but were followed by the desolation of the Dirty Thirties. The stock market crash and the Dust Bowl on the Prairies combined to produce the Great Depression, with unemployment reaching 27 per cent.

William Lyon Mackenzie King was prime minister in 1935, at the height of the Depression, a dull, reliable man, a lifelong bachelor with few friends and strong political instincts. He was our longest-serving prime minister and likely our oddest, regularly communicating with the spirit world—talking to his deceased mother, his dead dog, Philip the Apostle and Leonardo da Vinci, among others.

As the Depression dragged on, there was a new worry: the growing militarization of Germany. In 1937, King went to Germany to assess the situation for himself. Like Britain’s Neville Chamberlain, he came back believing peace was at hand. He also thought Hitler was a fellow spiritualist who talked to his dead mother. “I believe that the world will yet come to see a very great man—mystic, in Hitler,” King wrote in his journal.

Troops wounded in Operation Jubilee, the 1942 Allied raid on German-occupied Dieppe, France, were rescued by navy ships in the English Channel. [Glenbow Museum/NA-4548-5]

What the world saw was the imperialist ambitions of a nationalist fanatic, and on Sept. 10, 1939, Canada was once more at war. We were ill-prepared—the army largely untrained and its equipment outdated—and the Second World War once more raised the divisive issue of conscription. King wasn’t an inspirational leader; in many ways, he was the opposite of Winston Churchill, whose fiery speeches galvanized Britain. But King had a gift for finding a middle way (“Not necessarily conscription, but conscription if necessary”) and had a steady, if wildly eccentric, hand on the tiller.

Canadians suffered the disaster of Dieppe; 5,000 Canadians landed, and within hours there were 3,367 casualties. It was intended as an opportunity to test amphibious equipment and invasion strategies. After that, there was the bloody Italian campaign and the liberation of Holland. In the end, Canada once more distinguished itself in battle.

It has been said that Canada is separated by language and geography and held together by hockey. On March 17, 1955, these ideas came together in the Richard Riot in Montreal. In a game against the hated Boston Bruins, the beloved Canadiens star Maurice “Rocket” Richard retaliated against a high stick by breaking his stick over his opponent. When a linesman intervened, Richard punched him, knocking him unconscious. He was suspended for the rest of the season by league president Clarence Campbell.

Maurice “Rocket” Richard was the first NHL player to score 50 goals in one season, in 1944-45. [LAC/MIKAN-4871465]

When Campbell showed up at the Forum in Montreal for the next game, he was pelted with vegetables and punched by a fan. The game was suspended and fans rioted in

the streets, resulting in 37 injuries and 100 arrests. Richard’s suspension was seen by francophones as one more example of English oppression, and the Richard Riot was viewed as a precursor to the Quiet Revolution that gathered force a few years later.

Canada was formed, to a degree, in opposition to the Americans. They became our most trusted ally and remain our biggest worry, as they period-ically lurch between their highest ideals and lowest instincts. Our long-running relationship is given to periodical flare-ups and personal antagonisms. The relationship between Prime Minister John Diefenbaker and American President John F. Kennedy was rocky. The aging Prairie populist had nothing in common with the young charismatic eastern Brahmin. Diefenbaker thought Kennedy was shallow and privileged; Kennedy referred to Dief as an “SOB” in a memo.

This dysfunctional relationship came to a head over the threat of nuclear war. Canada was committed to the North American Air Defence agreement, which called for 56 Bomarc missiles armed with nuclear warheads to be stationed on Canadian soil. Diefenbaker decided not to allow nuclear warheads in the country at a time when the Cold War was heating up, culminating in the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, when the world was held in thrall for two tense weeks. Within a year, Diefenbaker, who now looked, and occasionally sounded, like an addled prophet, was washed away by the powerful riptide of the 1960s, replaced by Lester Pearson’s Liberals.

John Diefenbaker was Canada’s 13th prime minister, from 1957 to 1963. [G. Lunney/LAC/C-006779]

Pearson had already made his mark on the global stage with his plan to defuse the Suez Crisis. When Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser seized control of the canal, Israel immediately invaded and British and French planes bombed Egyptian airfields. The Soviet Union’s Nikita Khrushchev backed Nassar, threatening nuclear attacks if France and Britain didn’t withdraw. Again, the world was on the brink of war. Pearson proposed that the French and British withdraw, replaced by a United Nations force that would stabilize the situation. It was the first peacekeeping force, a concept that came to define Canada’s military role in successive decades.

In 1968, Pierre Trudeau took over the leadership of the Liberals and was elected in the era when television was having an impact on politics. Americans had chosen Kennedy’s cool grace over Richard Nixon’s sweaty furtive presence during the first televised presidential debate. Now Canadians were given the choice between Robert Stanfield’s earnest gawkiness or Trudeau’s hip persona. The result was Trudeaumania.

In 1980, Trudeau was faced with the existential threat of Quebec’s sovereignty referendum. He and the country weathered that crisis with a last-minute victory, despite early polls showing a majority of Quebecers would vote to leave. Trudeau alienated Quebec sovereignists with his tough talk, and that same year he angered Westerners with the introduction of the National Energy Program. Bumper stickers appeared on Calgary trucks: “Let the Eastern Bastards Freeze in the Dark.” National unity, always a challenge, was especially strained. Yet he was our third-longest-serving prime minister, next to King and Macdonald. And now his son is prime minister, an unlikely ascent.

When we look back, there have been great changes, even though much would be familiar to the Fathers of Confederation. Once more, the Americans represent a threat, driven by their president’s protectionist zeal and strident nationalism. First nations treaties are still being negotiated, and apologies issued for past wrongs. The West experiences periodic alienation, Quebec is occasionally aloof, and the Maritimes often feel neglected. We are constantly reminded that democracy is a process, that nationhood isn’t to be taken for granted.

There is much to cheer. In 1971, Canada was the first country to adopt an official multiculturalism policy. It is now one of the most multicultural societies in the world, and one of the safest. In an age when so many countries are erecting barriers, when nationalists are becoming dangerously shrill, when inequality and intolerance are on the rise, Canada is a beacon of tolerance and functioning democracy. We still possess the resources that caught the Old World’s eye, but now we offer a pluralistic model for the 21st century. In our quiet Canadian way, we are sauntering toward greatness.

Top Painting: Aboriginal peoples were justifiably wary of the arrival of European explorers. Samuel de Champlain established the Quebec colony in 1608; his ship was the Don-de-Dieu (gift of God). (G.A. Reid/LAC/C-011015;)

Advertisement