Many sailors owed their lives to this

durable, quick-launching raft

The corvette HMCS Louisburg was on escort duty off the coast of North Africa when she was hit by a torpedo dropped from an Italian plane at sunset on Feb. 6, 1943. In minutes, Able Seaman Budd Parks found himself injured, swimming in the pitch black, covered in oil, one of dozens “struggling for survival against time and the elements as darkness settled around us,” he recalled in Corvettes Canada: Convoy Veterans of WW II Tell Their True Stories.

“I was one of 42 crew members swarming around one Carley float designed to carry 12…Nineteen hours later, six of us were alive.” — John Gleason, survivor of HMCS Guysborough, sunk March 1945

Forty shipmates, including the captain, did not survive. Some were sucked under with the ship, more died when the boiler, torpedoes and depth charges exploded underwater. As darkness deepened, shipmates’ cries grew fewer and fainter. Fighting panic, Parks heard voices. “Voices meant a group. A group could mean a Carley float and a float would give me the required support for survival.”

And so it proved. Parks was among 50 survivors plucked from the Mediterranean that night, one of thousands of Canadian sailors who owe their lives to a Carley float.

Inventor Horace Carley, a whaler in his youth, began commercial production of the floats following news of a collision in dense fog in 1898 that sank the passenger liner La Bourgogne, says Clare Sharpe in the CFB Esquimalt Naval & Military Museum website entry about its restored float.

Newspaper reports at the time said only 165 of 714 aboard survived, largely because passengers and crew could not free the lifeboats in the 50 minutes it took the ship to sink. HMCS Louisburg sank in four minutes—but that was enough time to get Carley floats into the water.

“Horace Carley’s float was an important innovation,” says Sharpe. They were inexpensive, came in different sizes and could be nested for compact storage. Yet they were sturdy enough to take a “cruel battering.” Indeed, a shrapnel-riddled float, believed the sole relic of HMAS Sydney, was recovered weeks after the ship was sunk in battle with the loss of all 645 aboard in November 1941.

A poster for a wartime movie about survivors in a Carly float.

The float could be tossed into the water with no special equipment. It could be used immediately, no matter which side is up, and was so buoyant it could keep afloat many more men than it was designed to handle. Parks said the float he joined “lay about two inches below the surface due to overweight.” Louisburg cook W.R. Ransome added there were 13 men in his float, though it had been designed to support eight.

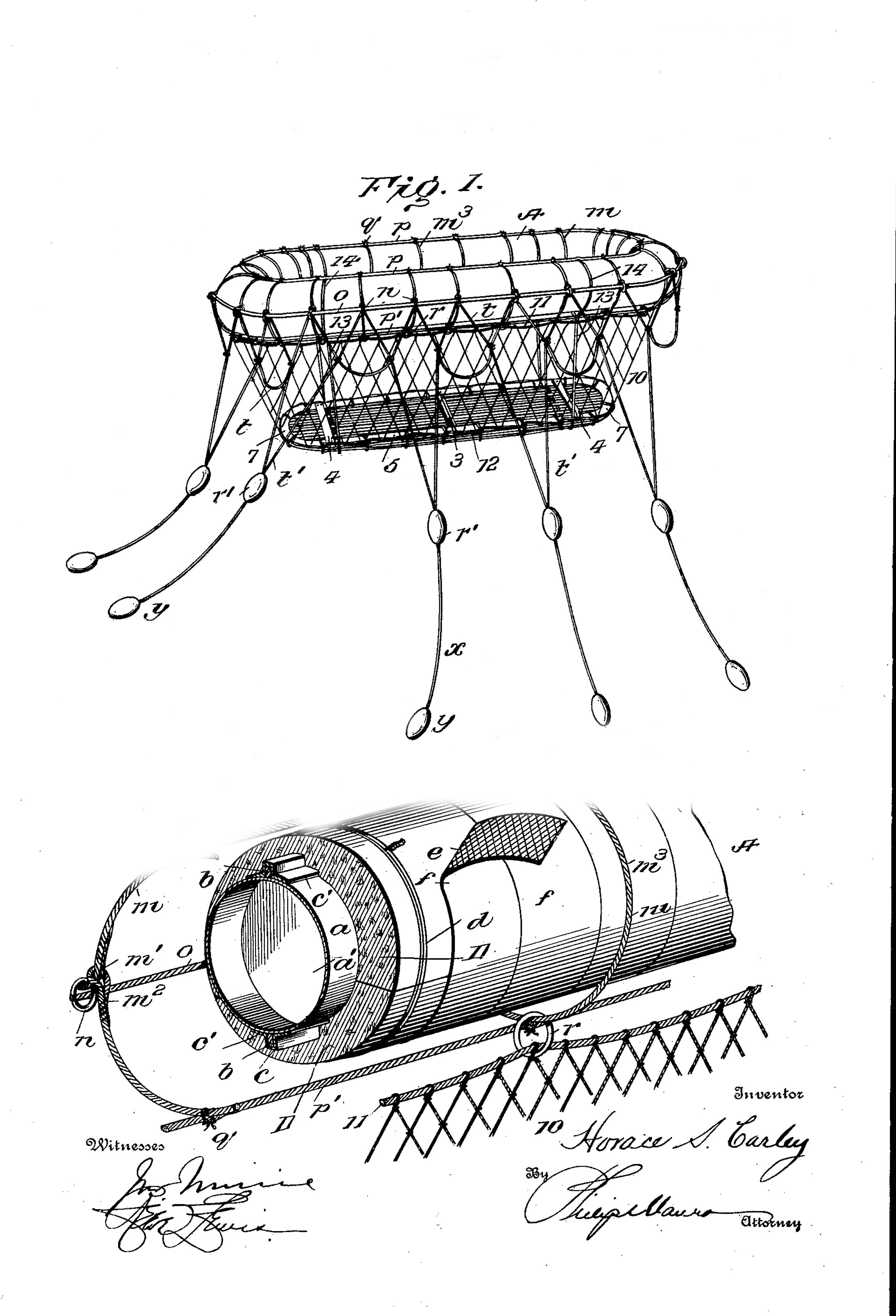

A Carley float is made of large-diameter copper tubing divided into individual water-tight compartments, something like an ice cube tray, then wrapped with cork and waterproofed canvas. It is shaped into an oblong doughnut shape and wrapped round with ropes, which serve as handholds.

Although these life vests were issued by the Canadian Navy in 1943, sometimes crew had no time to find and don them before abandoning ship. [A 2130]

A wooden floor supported by rope webbing can be extended, basketlike, below the water line. But this open design is also open to the elements. Many who survived a sinking succumbed to cold before they could be rescued.

It could keep afloat many more men than it was designed to handle.

Such was the fate of survivors of the minesweeper HMCS Esquimalt, sunk by a German U-boat within sight of the coast of Nova Scotia in April 1945, the last Canadian ship lost to enemy action. Esquimalt sank in four minutes. Forty-three sailors went into floats, but only 27 survivors were rescued from the frigid waters more than five hours later.

Rescue at sea: HMCS Esquimalt [DND/LAC/PA-107173]

75

Weight in kilograms of a float for six.

9 by 14

Dimensions, in feet, of a float to support 67.

30 to 90

Life expectancy, in minutes, for survival in water off Halifax in April.

Advertisement