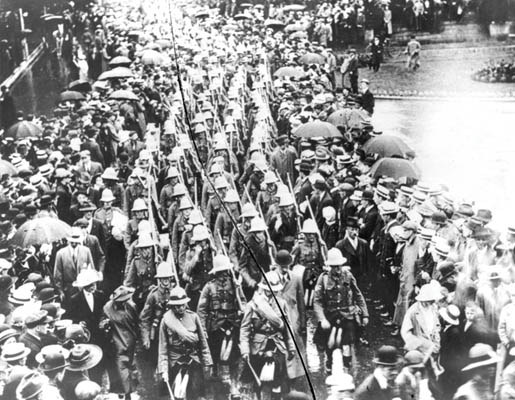

The 48th Highlanders (opposite) leave Toronto for overseas in September 1914. [DND/LAC/PA-001370]

In the fight for Festubert, combat for the “Canadian Orchard” cost 2,468 casualties.

The Canadians emerged from the battle for Ypres, Belgium, in 1915 with horrendous casualties: more than 6,000 men, including 1,410 who became prisoners of war. This casualty rate, 37 per cent of the troops engaged, would never be exceeded, not even at the Somme in 1916.

The British and Canadian press lauded the Canadian achievement and the enemy acknowledged their “tenacious determination,” but behind the scenes there were serious conflicts over the conduct of the battle, including sharp criticism of brigadiers Arthur Currie and Richard Turner. Many Canadian officers were equally unhappy with the performance of senior British officers. After April 1915, this tension helped to ensure that the 1st Canadian Division became the core of Canada’s national army, rather than an imperial formation drawn from a Dominion.

News of the gas attack and the valour of the country’s soldiers reached Canada on April 24, before the battle was over. The newspapers reported that Canadian “gallantry and determination” had saved the situation but hinted at heavy losses. The Toronto News described the mood: “Sunday was one of the most anxious days ever experienced in Toronto, and the arrival of the officers’ casualty list only served to increase the feeling that a long list including all ranks was inevitable. Crowds scanned the newspaper bulletin boards from the time of arrival of the first lists shortly before noon, until midnight, while hundreds sought information by telephone.”

At first it was impossible to believe that battalions such as the 15th, made up of men from Toronto’s 48th Highlanders, had been wiped out. The press assumed that many were prisoners of war, as historian Ian Miller describes in Our Glory and Our Grief. But awareness soon dawned that whole battalions had been devastated. When full lists became available in early May, the truth was apparent: “Half the infantry at the front have been put out of action.”

The events of the spring of 1915 transformed the war from a great adventure to a great crusade. A week after the enemy introduced the horrors of gas warfare, the British ocean liner RMS Lusitania was torpedoed off the coast of Ireland with the loss of 1,369 civilians, including 150 children. Newspapers across Canada published heart-rending stories about the victims and survivors of the sinking alongside further accounts of the fighting in the Ypres Salient.

Revisionist accounts of the Great War have sought to minimize German war crimes in 1914-15, but at the time, Canada’s people recognized policies designed to inspire terror for what they were. This was particularly true after the first gas attack when, to cite just one example, a letter from the front printed in the Toronto World informed readers that, “…the dead are piled in heaps and groans of the wounded and dying never leave me. Every night we have to clear the roads of dead in order to get our wagons through. On our way back to base we pick up loads of wounded soldiers and bring them back to the dressing stations.”

The censors could do little to prevent the publication of such letters and they proved equally unable to control the content of articles on the war. One attempt to stop the publication of Robert W. Service’s gritty descriptions of his experiences as an ambulance driver was ignored by editors determined to print front-line reports from the popular author and poet. Service’s description of the trenches, with its images of “poor hopeless cripples” and a man who seemed to be “just one big wound,” left no room for doubt about the ugliness of war. Despite such realistic accounts of combat, the events of May 1915 inspired Canadians to volunteer in record numbers, doubling the army’s strength to 200,000 men in just six months.

Brigadiers Arthur Currie Richard Turner (below) were criticized behind the scenes for losses at Ypres. [LEGION MAGAZINE ARCHIVES]

The losses suffered by Second British Army at Ypres did not lead to any change in plans to support a new French offensive intended to secure Vimy Ridge. The British contribution was an attack on Aubers Ridge, designed to draw reserves away from Vimy. Despite evidence that the Germans had greatly strengthened their defences, the attack began on May 9 and quickly turned into a costly disaster. “Defeat was swift, bloody and complete,” as J.P. Harris writes in Douglas Haig and the First World War. A second attempt later the same day was an “unmitigated disaster,” with losses of 10,000 men, of whom one in four died.

The failure at Aubers Ridge did not end demands for continued action on the British front. General Douglas Haig decided to leave the ridge to the enemy and try his luck farther south at Festubert, France. His new plan called for a pincer movement to be preceded by a lengthy bombardment rather than the 40-minute “Hurricane” barrage used at Aubers Ridge. For the first time, a prepared attack was to begin at night. The cost of the action, which gained modest and meaningless ground, was more than 12,000 British casualties.

Governor General the Duke of Connaught inspects an automobile machine-gun battery in Ottawa in September 1914. [DND/LAC/PA-004913]

Haig was running out of men, and he ordered the Canadians to join the battle. Reinforcements from reserve battalions in England brought the Canadians back up to strength but there had been no time to integrate the replacements. Within hours of their arrival, the 14th Battalion (Royal Montreal Regiment) and 16th Battalion (Canadian Scottish) began a daylight attack across flat, wet fields intersected by deep ditches. Forced to the ground by enemy fire, both battalions dug in and waited for darkness.

The rest of the division arrived the next day and, despite Lieutenant-General Edwin Alderson’s plea for time to study the situation before committing his troops, Haig insisted on immediate action. Two days of intense close combat for what would be called the Canadian Orchard ensued. The price: 2,468 casualties.

Coming so soon after the struggle in the salient, Festubert was a shock to many Canadians. BrigadierArthur Currie complained bitterly about the lack of preparation and inadequate support while Canadian Minister of Militia Sir Sam Hughes wrote a scathing attack on Alderson, which he sent to Prime Minister Robert Borden and British Secretary of State for War Lord Kitchener. As always, Hughes went off the deep end, but his criticisms should not be entirely ignored. The fruitless attacks at Festubert, which Hughes described as “attempting to gain a few yards…with no preconceived plan of an effective drive to smash the enemy,” are an accurate picture of the engagements that cost First British Army 16,000 casualties.

Haig took a very different view of Festubert, insisting that a new attempt to break through the German defences and exploit into open country would succeed if a longer preliminary bombardment were employed. Thus the battle for Givenchy began with 211 guns firing for 48 hours before two British divisions attacked in the early evening of June 15. Haig and General Henry Rawlinson, the Corps commander responsible for the action, were in sharp disagreement over the purpose and scope of the operation. Rawlinson continued to argue for a measured “bite and hold” approach, while Haig insisted on yet another attempt to break through and exploit. Givenchy quickly turned into another costly disaster for British troops. Under Brigadier Malcolm Mercer, 1st Canadian Brigade played a supporting role, protecting 7th British Division’s flank. Neither the British division nor the Canadian brigade made any significant progress and the operation was called off on June 18.

Allied losses in May and June 1915 totalled more than 200,000 men, a number that ought to have demonstrated that battles could not be won with the weapons and tactics used in 1915. The British and French field commanders were convinced that with more and better shells for the artillery, including ones filled with gas, they would break the German defences. Lord Kitchener, who was striving to create a “New Army,” which would place 50 divisions in the field, was less sure. He was preparing for a long war, but admitted he had no idea how it might be won. It is evident that the British generals, like their French and German counterparts, were totally surprised by the harsh realities of trench warfare. They simply had no idea of how to get men across the zones of machine-gun, mortar and artillery fire to close with the enemy. They were equally unprepared to exploit any breaches in their opponents’ defensive positions.

With a few outstanding exceptions, senior British officers demonstrated a profound lack of imagination and initiative in the early years of the war. The first suggestions for a tracked armoured vehicle that could overcome barbed wire and cross trenches were made in Britain during the fall of 1914, but the army was not interested.

Instead, experiments were carried out by the Royal Navy’s Landships Committee, formed by Winston Churchill through his control of naval expenditures when he was First Lord of the Admiralty. The first such vehicles, called ‘tanks’ for security reasons, were ready for use in July 1916, although another year passed before large numbers were available. In early 1915, the French army issued steel helmets, which saved many lives, but British and Canadian troops had to wait another year before helmets became standard issue. Germany made early use of trench mortars, but it took 11 months to authorize the mass production of the British-invented Stokes mortar. The public was not aware of these problems, but was informed of the shortage of Allied machine guns, which was said to account for German success in trench warfare.

The machine-gun movement became a popular crusade in Britain and was launched in Canada by John C. Eaton, of the department store family, who donated $100,000 to purchase armoured cars with Colt machine guns. The concept of motorized armoured machine-gun carriers was an initiative of Raymond Brutinel, a former French officer and immigrant to Canada, who organized “the first motorized armoured unit formed by any country during the war,” according to Cameron Pulsifer of the Canadian War Museum. Brutinel’s 1st Canadian Motor Machine Gun Brigade was reinforced by batteries formed in Canada, although the static conditions on the Western Front provided little opportunity for mobile warfare and before 1918, the brigade was used primarily in a fire-support role.

Advertisement