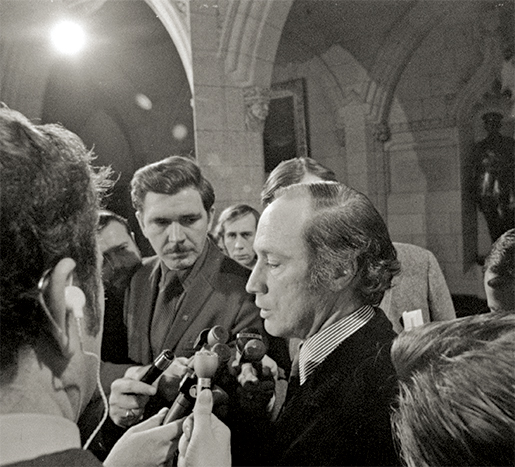

Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau makes a statement to the press following the release of James Cross in December 1970. [PHOTO: DUNCAN CAMERON/LAC/PA-110806]

Author D’Arcy Jenish says YES.

Author Reg Whitaker says NO.

D’Arcy Jenish is a freelance writer and author of nine books. He is currently at work on a history of FLQ terrorism that culminated in the October Crisis. Reg Whitaker is Distinguished Research Professor Emeritus at York University. He is the co-author of Secret Service: Political Policing in Canada from the Fenians to Fortress America.

D’Arcy Jenish

YES

Pierre Trudeau is remembered today for many things—the introduction of official bilingualism, the repatriation of the constitution and creation of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the National Energy Program and, of course, the proclamation of the War Measures Act on Oct. 16, 1970, after the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) separatist paramilitary group kidnapped British Trade Commissioner to Canada James Cross, and, a few days later, Pierre Laporte, Quebec’s Deputy Premier and Minister of Labour.

Trudeau and his cabinet acted at the request of Quebec Premier Robert Bourassa and Montreal Mayor Jean Drapeau. All three administrations believed that a state of “apprehended insurrection”—as the Act’s proclamation declared in 1970—existed in the province. Regulations accompanying the Act made it illegal to belong to the FLQ or similar organizations and severely curtailed the rights of freedom of expression and association for anyone who belonged to, or was associated with, these groups. The regulations also granted emergency powers to the police, who promptly arrested more than 450 people, without warrants and without laying charges, detaining them for as little as a few hours and for as long as several months.

Public opinion showed that 85 to 90 per cent of Canadians supported these extraordinary measures. Newspaper editorials across the country backed the government, but civil libertarians, federal New Democratic Party leader Tommy Douglas and a few Conservative members of Parliament did not.

A funny thing has happened in the nearly half century that has elapsed since then. Almost everyone who has written about the October Crisis, as it became known, has criticized the use of the War Measures Act. Some have ridiculed the notion that an “apprehended insurrection” existed and almost all have condemned the arbitrary arrests and detentions. They’re wrong, and here’s why.

Montreal police were desperately trying to locate Cross and his abductors, while the provincial Sûreté du Québec were conducting an equally frantic search for Laporte, who was being held in a suburb on the city’s South Shore. At the same time, separatist agitators, militant labour leaders and student activists were organizing strikes and demonstrations in support of the FLQ.

These groups possessed an enormous capacity to create chaos in the streets. They were behind three major riots in Montreal between June 1968 and October 1969, as well as numerous demonstrations and disturbances that sometimes attracted crowds of 25,000 or more. Then there was the pro-FLQ rally at Paul Sauvé Arena the night before the War Measures Act was implemented, which ended with several thousand students chanting: “FLQ, FLQ, FLQ.”

The Act put a stop to these actions and allowed the police to get on with their work. The arrests had the same effect. Some people—supporters of Quebec independence, but not the FLQ—were wrongly detained. But the police dragnet took a lot of FLQ sympathizers off the street and deterred others who were inclined to support the kidnappers directly or indirectly.

Finally, those who criticize the War Measures Act make the fundamental mistake of ignoring the FLQ’s politically inspired terrorism that began in the spring of 1963. The terrorism occurred in waves and included bank robberies, armoury heists, burglaries, thefts and bombings—more than 200 bombings in the Montreal area between 1963 and 1970. Five people died in explosions or shootouts and property worth millions was damaged or destroyed. Nothing even remotely comparable had ever occurred in Canada or the United States.

By October 1970, extraordinary measures were required. As a Vancouver Sun editorial put it after Trudeau proclaimed the War Measures Act: “At last, the government has armed itself to fight fire with fire and match ruthlessness with ruthlessness.”

REG WHITAKER

NO

On Oct. 5, 1970, gunmen kidnapped British Trade Commissioner James Cross from his Montreal home. In exchange for his life, the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) made a series of political demands. The Canadian government refused to negotiate with the terrorists, instead launching a major police operation to recover Cross. Within days, another FLQ cell kidnapped Pierre Laporte, Quebec’s Deputy Premier and Minister of Labour.

The dimensions of this crisis were larger than the lives of the two hostages, as important as these were. Quebec separatism, both the violent FLQ version and the lawful variety represented by the Parti Québécois, had been rising throughout the 1960s. The federal Liberal government of Pierre Trudeau, with its strong base in Quebec, was determined to hold the country together.

The Trudeau government responded with an iron fist. In the early hours of Oct. 16, citing an alleged “apprehended insurrection,” it invoked the War Measures Act, a statute previously employed during two world wars that suspended peacetime civil liberties, permitted detention without habeas corpus or legal representation and directed censorship of the media. More than 450 people were swept up in police raids and detained, most ultimately released without charges. None led to the cells holding Cross and Laporte.

The FLQ responded to the War Measures Act by murdering Laporte. Finally in December, through careful police work rather than emergency powers, Cross was located and released.

The War Measures Act was irrelevant to the actual resolution of the crisis, and failed to save the life of Laporte. The Act was, in effect, the ‘nuclear option’: a war measure applied in peacetime. Unsubstantiated alarms about the magnitude of the threat posed by the FLQ were rife, many emanating from Trudeau’s own ministers—one even asserted that the FLQ had enough dynamite to blow up the centre of Montreal. No evidence was ever brought forward to back the claim that the FLQ, a small group of fanatics, posed any real threat of civil insurrection.

The RCMP security service was unimpressed by the FLQ’s revolutionary potential. If the RCMP had been asked, they would not have advised the use of the War Measures Act. The RCMP considered that the mass detentions—including singer Pauline Julien and other celebrity separatists—had only wasted police time and extended the length of the crisis. One senior RCMP official testifying before a federal inquiry put it bluntly: “You don’t need an atomic bomb for a riot on St. Catherine Street.”

Liberals, including Trudeau himself, later asserted that they had needed emergency powers because they had been left unprepared by inadequate intelligence on the FLQ. Declassified documents call this into question: the Mounties were reasonably informed about the identities and activities of FLQ activists.

Public opinion was, initially, strongly favourable to the War Measures Act. But over the years doubts grew. The federal use of war powers in Quebec fed a growing alienation of Quebecers from federalism. Six years after the crisis, the Parti Québécois came to power in Quebec. The Conservative government of Brian Mulroney repealed the War Measures Act, replacing it in 1988 with the Emergencies Act, a more measured statute that provides graduated emergency powers proportionate to the level of threat.

In retrospect, the use of the War Measures Act was an overreaction to a threat that, while real enough to cost the life of Pierre Laporte, did not constitute grounds for suspending civil liberties in peacetime. It would not be the last time that a government has seized on terrorist threats to shift the balance sharply away from liberty to security. Thanks to the experience of the October Crisis, Canadians are perhaps now more reluctant to be panicked into giving away their hard-won liberties.

Advertisement