Canada’s air force was born in fits and starts

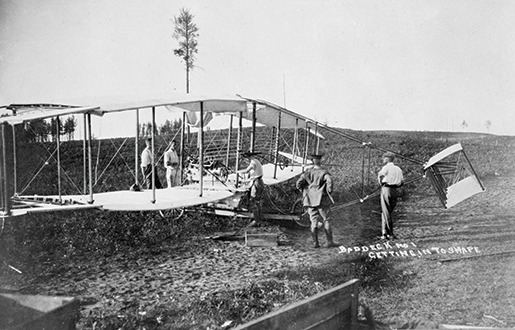

The first aircraft designed and built in Canada, the Baddeck No. 1, made its first flight—of 100 metres—at Camp Petawawa, Ont., on Aug. 11, 1909. [LAC/e011157164]

The Canadian Militia was exposed to aircraft at Camp Petawawa in July and August 1909. Canadian aviation pioneers John McCurdy and Frederick Baldwin were permitted to demonstrate their two aircraft—the Silver Dart and the Baddeck No. 1—before officers and the deputy minister of militia. Neither machine put on a creditable performance before crashing. The demonstration was perhaps a year too soon; it managed to postpone Militia interest in the airplane for years. A few middle-ranking officers tried to secure government support for the new technology, but departmental attitudes ranged from indifference to hostility.

In September 1914, Minister of Militia and Defence Colonel Sir Samuel Hughes abruptly authorized an unknown adventurer, Ernest Lloyd Janney, to buy an airplane, form the Canadian Aviation Corps (CAC) and accompany the First Canadian Division to England. By February 1915, the CAC had disappeared and Janney, back in Canada, had launched himself on a career as a con man. No Canadian air force would appear until the closing months of the war, and even that would not see combat.

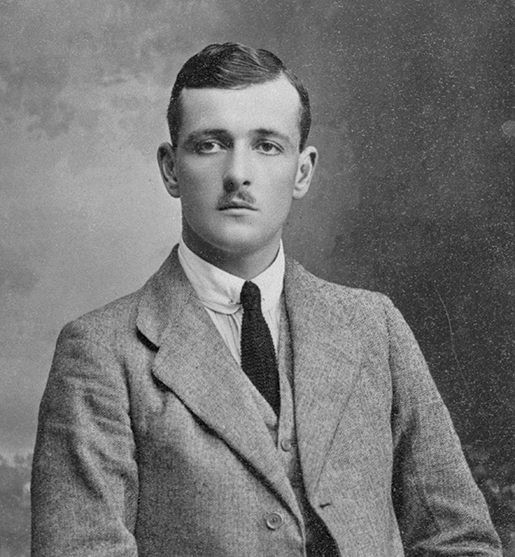

Frederick Wanklyn of Montreal was among the earliest Canadian aviators to join the British flying services, in 1912. [LAC/e011157165]

We do not know how many Canadians there were. In the Memorial Chamber in the Peace Tower, it states that 22,812 Canadians so served. The number has never been substantially verified. In 1919, a Canadian War Records survey (incomplete and with some documentation now lost) came up with a figure of 9,600. Other studies have boosted that to 13,160, to which might be added 7,453 mechanics recruited in Canada in 1917-18, for a total of 20,613. This still leaves us 2,200 short of the Memorial Chamber figure.

Counted in these statistics are some 1,756 known Americans who joined via Canada. The “Canadian” credentials of a further 4,520 are uncertain. There was no such thing as “Canadian citizenship” until 1947, and thousands of Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) volunteers were recent British immigrants; other such immigrants may have gone back to England to enlist in British units.

Whatever the numbers, how did they get there?

Canadians trickled into the British flying services by different means. There was no air recruiting office in the Department of Militia, but British officers on the Governor General’s staff found numerous young men volunteering to join the flying services. After April 1915, these officers actively sought out enlistments.

Malcolm McBean Bell-Irving of Vancouver was among one of the earliest Canadian aviators to join the British flying services, in 1912. [LAC/e011157166]

The RNAS continued to recruit young men in Canada until January 1918; some 635 men were raised. About half paid for their initial flight training before going overseas. Informal RFC recruits numbered about 350 to the end of 1916.

When the Canadian recruits arrived in England, they found that a few compatriots had preceded them into combat aviation. Capt. Frederick Wanklyn of Montreal, a graduate of Royal Military College, had been commissioned in the British Army in 1909, learned to fly and was seconded to the RFC in November 1912. Late in 1914, Wanklyn was flying reconnaissance missions in France. He was awarded a Military Cross in May 1915 and ended the war as a lieutenant-colonel.

Another early arrival was Malcolm McBean Bell-Irving of Vancouver. In August 1914, he paid his own way to Britain, was gazetted as a lieutenant in the RFC in September, and then followed the rudimentary pilot training of the day. On Dec. 29, 1914, he reported to No. 1 Squadron in France. Through the war, he was wounded twice, had at least one flying accident, was twice mentioned in dispatches, and was awarded the Military Cross and the Distinguished Service Order.

Most of the Canadians in the flying services were those who transferred from the CEF. This began almost as soon as the First Canadian Division reached England. Redford Henry Mulock of Winnipeg, a McGill graduate in electrical engineering, arrived in October 1915 as an acting corporal in a cavalry unit. By January 1915, he had received a discharge from the CEF and joined the Royal Naval Air Service, an unusual path. By November 1918, he was a colonel—the highest rank attained by any Canadian in the wartime RAF—and in command of a force of Handley-Page V/1500 heavy bombers that were waiting for suitable weather to attack Berlin.

Unlike the Australian Imperial Force, the CEF was fairly liberal about allowing such transfers, with only occasional protests that the army was losing too much talent to the flying services. Many began as an informal “attachment” to a flying field unit (usually as an observer), which led subsequently to pilot training. William A. “Billy” Bishop was an example.

Casualties and expanding RFC operations led to the establishment of the Royal Flying Corps (later Royal Air Force) Canada Scheme in 1917-18. The RFC and Imperial Munitions Board established a recruitment system, an aircraft factory, and a network of bases that trained pilots and observers and kept everything in running order. It was essentially a British operation in Canada—senior officers were all British—although the system was increasingly manned by Canadians, many of them veterans of the 1916-17 air campaigns. By November 1918, some 60 per cent of the instructors and 12 of the 16 training squadron commanders were Canadians. Major Albert Godfrey of Killarney, Man., commanded the prestigious School of Aerial Fighting at Beamsville, Ont.

The Canadian training scheme graduated 3,135 pilots (2,500 were sent overseas) and 137 observers (85 were sent overseas). As mentioned above, 7,453 mechanics enlisted for service in Canada and abroad. Some 1,200 women were recruited as clerks, mechanics and vehicle drivers. Untold more worked at Canadian Aeroplanes Limited, which manufactured 1,200 complete JN-4 training aircraft and the equivalent of 1,600 more in parts.

Many young Canadians, hoping to join the British flying services in the First World War, obtained pilot certificates at private flying schools in the United States. Lloyd S. Breadner (at left) of Ottawa and instructor John Simpson sit at the controls of a Wright Model-B biplane. Breadner became a distinguished fighter pilot and an air marshal in the RCAF. [LAC/e011157163]

But it was events closer to home that sped matters up. German submarines operated off the East Coast in 1917; they returned in 1918, emphasizing the need for air patrols. As a stop-gap measure, flying-boat stations were established at Dartmouth and Sydney, N.S. The aircraft and personnel were members of the United States Navy, but it was intended that a Royal Canadian Naval Air Service (RCNAS) would take over. The service was authorized on Sept. 5, 1918, and started recruiting and training ground technical personnel, but with the armistice on Nov. 11, 1918, the RCNAS was promptly disbanded.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant-General Sir Richard Turner, commander of Canadian forces in England, had picked up on Borden’s idea of a Canadian Flying Corps. He was supported by Sir George Perley, Canadian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom, in lobbying for such a body. By the summer of 1918, at least one-quarter (possibly one-third) of the RAF was Canadian and the British were reluctant to permit a major reorganization (and disruption) just as the war was reaching a successful climax.

Nevertheless, a distinct Canadian Air Force was authorized on Sept. 19, 1918. Two British squadrons were designated No. 1 (Fighter) Squadron and No. 2 (Day Bomber) Squadron, and posting of Canadians to these units began. Suddenly, peace broke out.

The CAF never flew an operational mission (although most of its aircrew were seasoned veterans), but it lasted for several months. When Britain offered 100 airplanes to every Commonwealth country to help establish national air forces and services, CAF personnel chose the gift aircraft and supervised their packing and shipping to Canada.

On May 30, 1919, the Cabinet ruled that Canada did not need and could not afford a post-war air force, and the CAF was disbanded. However, with the formation of the Air Board, Canada’s first governing body for aviation with both civil and military functions, a crack opened for a new CAF to be organized, first on paper and then as a part-time reserve. On April 1, 1924, the formation of the permanent and professional Royal Canadian Air Force effectively reversed the 1919 Cabinet decision.

Advertisement