No boost for defence spending

When Finance Minister Bill Morneau delivered the Liberal government’s 2017-18 budget in March, the surprise to many observers (and incurable optimists) was that there was, fundamentally,

When Finance Minister Bill Morneau delivered the Liberal government’s 2017-18 budget in March, the surprise to many observers (and incurable optimists) was that there was, fundamentally,

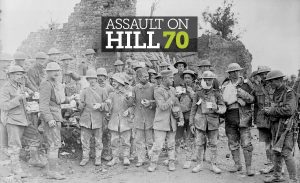

The year is 1917 and the place is northern France. The meticulously prepared Canadians sweep up the commanding heights in the face of determined German resistance

“I’m trying to differentiate myself not as the injured ex-military guy,” says Christian Maranda. “I’m trying different things. It makes me feel alive.” Story and

For 60 of the past 62 years, the World Press Photo competition has been holding a mirror to the world we live in, and it’s

Fred Caron’s nightmares started on his first night back in camp after the siege Story and photography by Stephen J. Thorne The one thing about

Get the latest stories on military history, veterans issues and Canadian Armed Forces delivered to your inbox. PLUS receive ReaderPerks discounts!

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

Free e-book

An informative primer on Canada’s crucial role in the Normandy landing, June 6, 1944.