It was 1967 and winter was fast approaching for Frank Worthington. The renowned retired major-general, who to this day is known throughout the Canadian military as “Fighting Frank,” was dying of cancer.

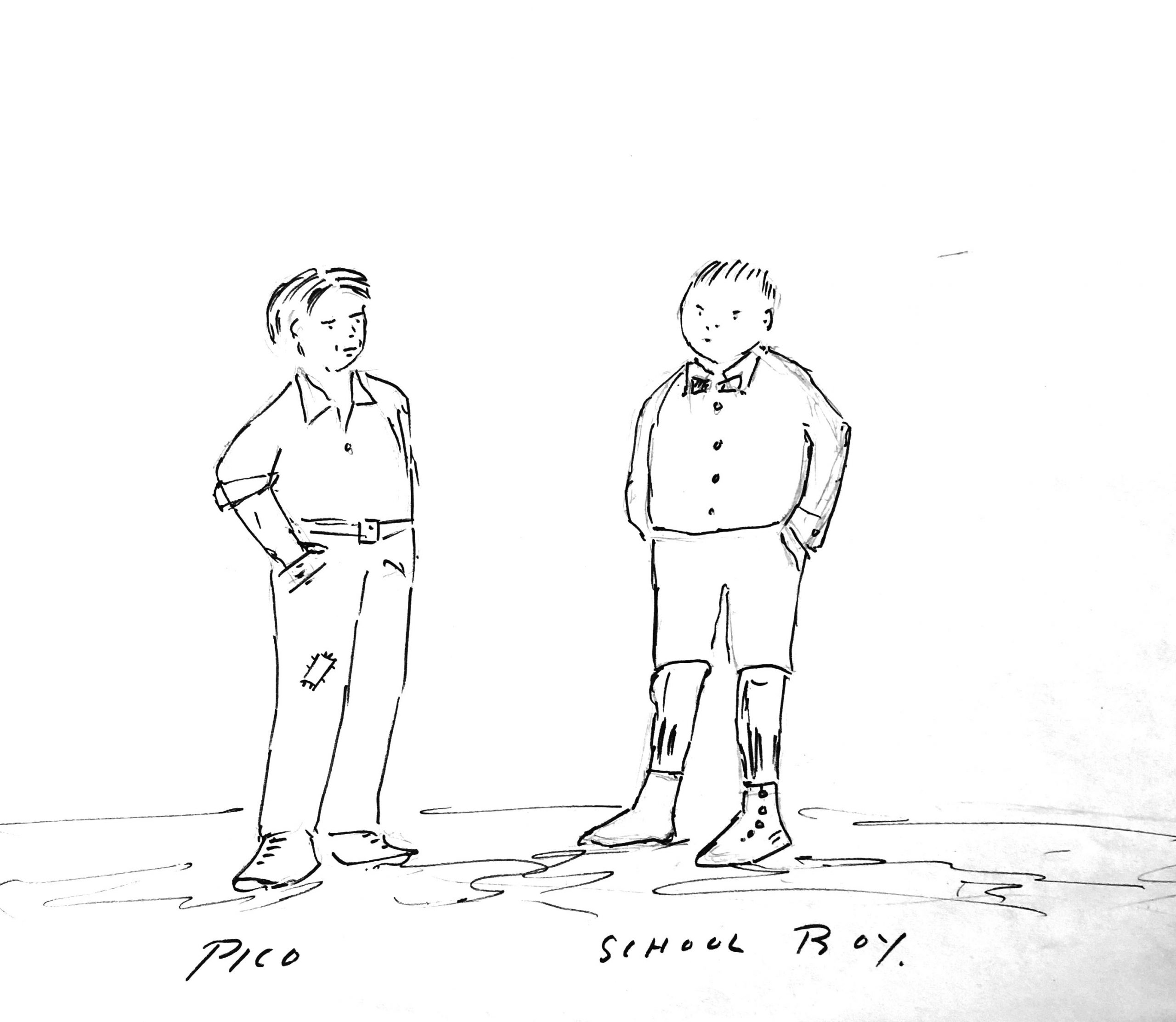

“Pico”…

“Fighting Frank”…

“Worthy”…

“Frederic Franklin”…

“Father of the Royal Canadian Armoured Corps”….

His multiple monikers only hint at the remarkable life of Major-General

F.F. Worthington

In his study there was a typewriter. It clacked regularly in the months preceding his diagnosis as Worthington, determined as ever, wrote down his recollections. They were not what you might have expected from a man whose career and reputation have been so tightly woven into the fabric of this country’s military history.

The reminiscences that poured forth were not of the Great War battle that won him the Military Medal, nor of the command battle 25 years later when he was edged out of leading the 4th Canadian (Armoured) Division and reassigned home in the months before D-Day.

That life had already been dutifully and lovingly chronicled by his wife Clara Ellen (Larry) in a 1961 biography titled Worthy.

The stories that preoccupied Worthington at this stage of his life were deeper and perhaps more precious to him. Gently urged on by his daughter Robin, he set to paper the extraordinary account of his childhood growing up as an orphan at the turn of the 20th century in the vast, violent, sunbaked hills of northern Mexico.

“My mother was probably much more drawn to this part of his life and this part of him,” said Linnet Fawcett, Robin’s daughter and Frank’s granddaughter, “than to the man with the military career, which had been much recorded elsewhere.”

A handwritten note to Robin was pinned to the unfinished manuscript.

“You have saddled yourself with the Pico Story,” Worthington told his daughter. (He was nicknamed Pico by those who knew him in those days. It was an affectionate moniker his grandchildren would also adopt.) “Otherwise I would not have started it. By this, I mean you are the inspiration.”

In one of his other notes, he expressed regret at not being able to see his grandchildren grow up. Linnet said she believes the text was intended “in part, to make himself known to us—child to child.”

Worthington died on Dec. 8, 1967, and the manuscript became part of the family papers.

Robin was the sole guardian of the story, it seems, and at one point in the 1990s shared it with her brother, accomplished foreign correspondent and founding editor of the Toronto Sun, Peter Worthington.

Robin’s son and Frank’s grandson, Matthew Fawcett, said Peter did have the manuscript. “He may have put it aside with intent to do something with it, but never did,” said Fawcett. “Perhaps like all of us, he didn’t quite know what to do with it.”

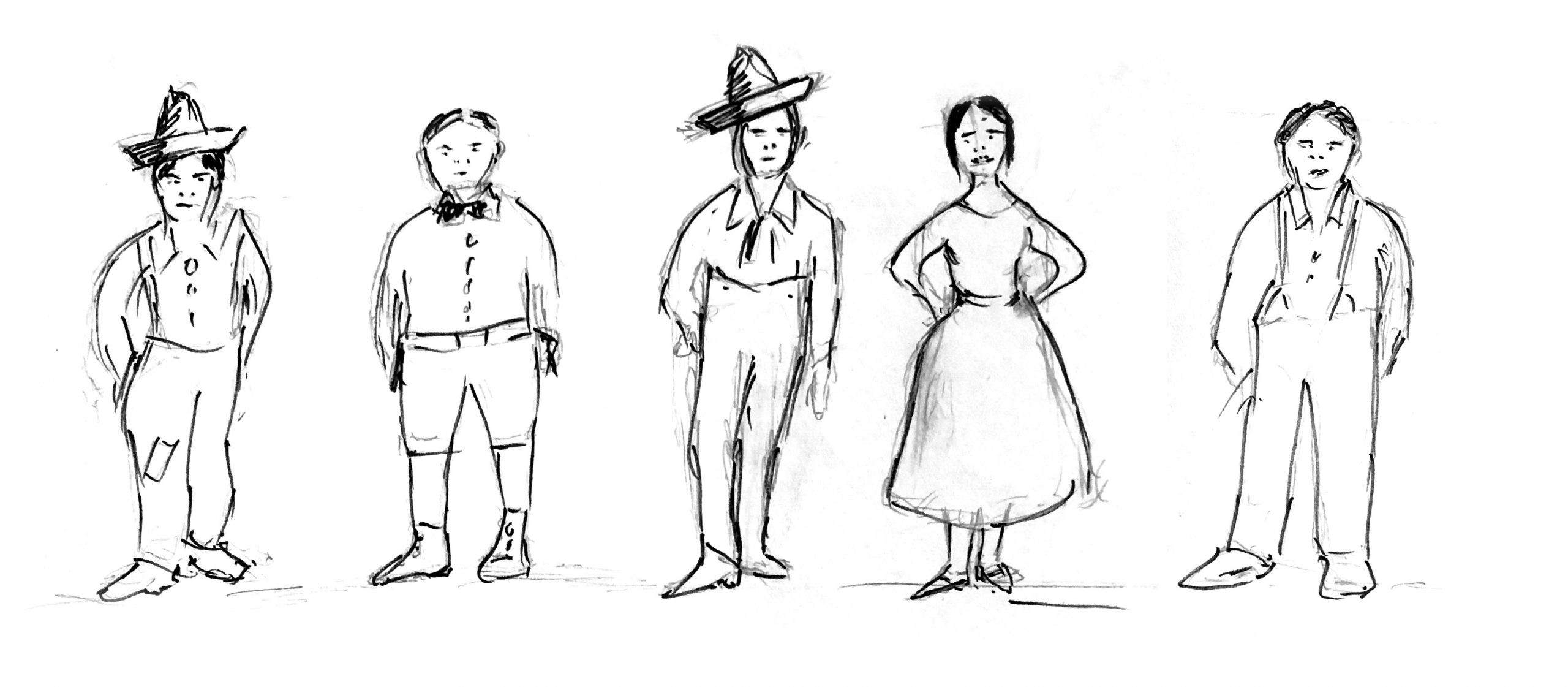

For more than five decades, the unfinished work and accompanying hand-drawn illustrations, have lingered in boxes, unread and unknown outside of the immediate family.

What survives today is a richly woven series of vignettes and character sketches—hard places, brutal events and uncomplicated people, who were long ago given up to history.

There is a touch of To Kill a Mockingbird, perhaps even Huckleberry Finn, in parts of the narrative; less in the writing style than in the point of view. We are introduced to people living hard lives and to the coarse injustice of the time as seen through the unwavering eyes and sensibilities of a child.

His story is compelling, heartfelt, and at times heartbreaking.

Legion Magazine was granted access to the manuscript by Worthington’s grandchildren. It is a fascinating, personal glimpse at one of the most influential figures in Canadian military history, told in his own words.

Frederic Franklin Worthington was born in Peterhead, Scotland, on Sept. 17, 1889. At an early age, he moved with his parents to California.

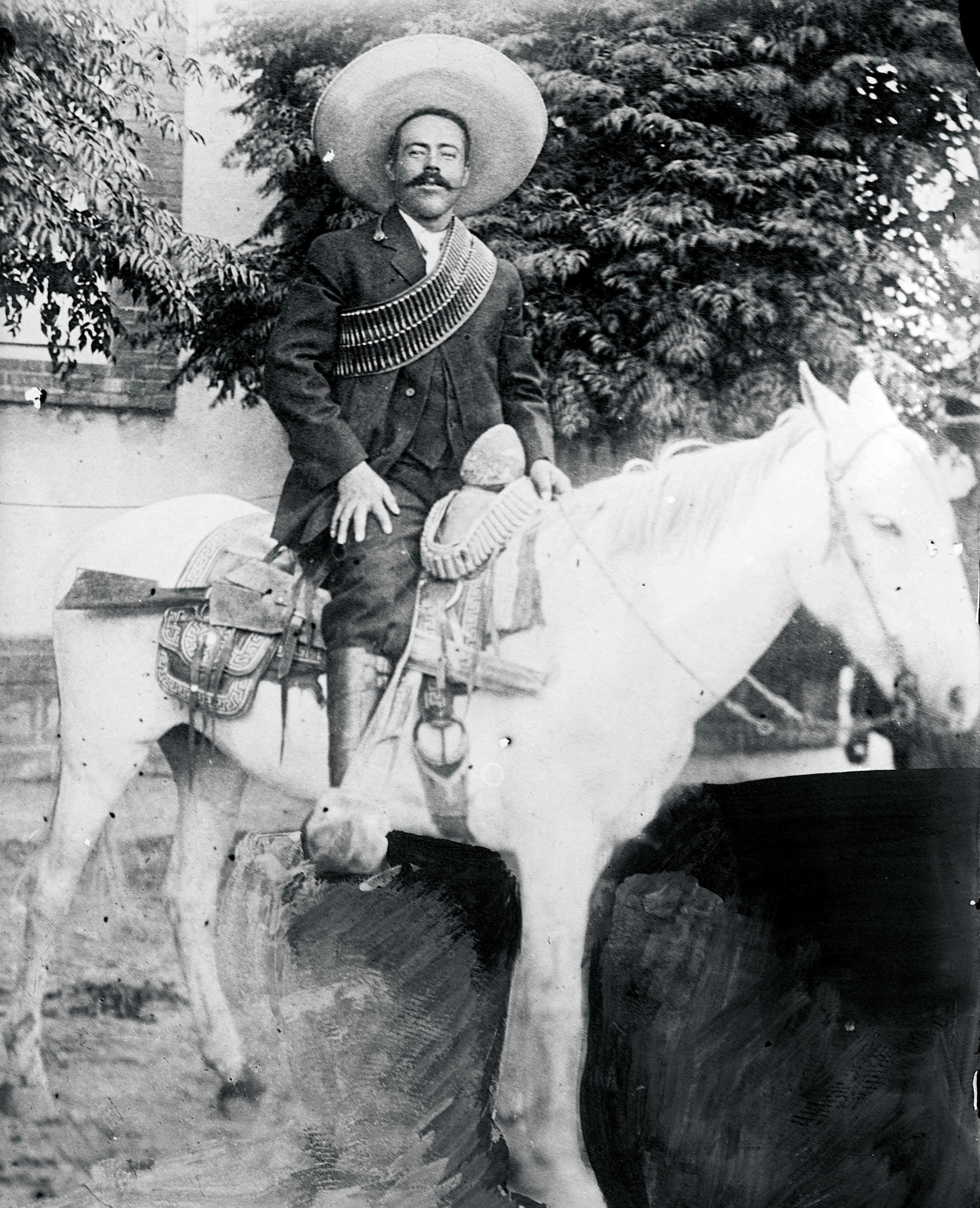

Within a few years, his mother and father were both dead, possibly of influenza. At the age of 11, he was sent to live with his older half-brother who was a mine engineer in Nacozari de García, Mexico. A year later his brother was killed when the mining office was raided by the notorious Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa. Worthington was 12 and alone in the world.

The manuscript picks up the threads of his life shortly after his brother’s murder. He places the reader square in the middle of the desolate little town of low-slung houses amid scorched and lifeless hills.

“The landscape was dull grey or burnt 99 per cent of the time, where the sun beat down and drained the skin leather dry. The dry riverbeds were caked with hard-baked yellow dirt,” wrote Worthington, calling it a place where the weather was the “same as yesterday and the day before, and would be the same tomorrow and the next day.”

The people were just as bleak. It was a rough place, full of shady characters. The town, about 300 kilometres from the United States border, was filled with the desperate, the forsaken and the forgotten of the Gilded Age.

“Men came and went, one never asked from where or whence, but many had been soldiers,” he recalled. “There were some veterans of the Crimean War and plenty of American Civil War soldiers, as well as those who had fought the Indian wars.”

The sensibilities of the Old West—already dying out in America—continued to linger in the place where Worthington had found himself.

“There was very little crime so long as the occasional gunfight was excluded,” he wrote, noting that frontier justice was peculiar and selective. “Like all mining towns in northern Mexico, there were a great many whites, or Gringos, and this was because the mine and smelter employed a lot of engineers and other types of skilled workmen not available among the Mexican people.

“It did not appear to be an offence for a Gringo to shoot another Gringo or for a Mexican to shoot Gringos, but if a Gringo shot a Mexican he was in real trouble and had better get out forthwith.

“Any person deemed undesirable for some reason would be told to vamoose and that was that.”

Worthington was taken in by an older Englishman by the name of Grindel (we never learn his first name), a worldly, well-educated “remittance man”—an emigrant paid to stay away from his home country—whose housekeeper was a young Mexican woman, a former dance hall girl, named Chiquita. Living with Grindel was both a “pleasure and an ordeal.” The older man had no set routine for anything, even breakfast.

“The landscape was dull grey

or burnt 99 per cent

of the time.”

Worthington was remarkably clear-eyed and self-aware as a child. Curiously, throughout the manuscript, he refers to himself in the third-person, almost as if his childhood had happened to someone else.

“As a little boy of about 10 years old, Pico did not believe that he was a little boy because he was just as big as the other boys his age,” wrote Worthington. In a later moment of reflection, he scribbled in the margin of the manuscript: “This was a foolish way of thinking.”

There was a touch of melancholy in some of his observations, as if the old man with the typewriter saw what the young boy had missed.

“Pico was like any other little boy except that he did not wear short pants and long stockings as did the boys who went to school,” wrote Worthington.

“He did not go to school because he had no home and could not pay for school, so he had to work in order to earn money to pay for his food and clothing and other things.”

Grindel was the source of much of Pico’s early education. They would discuss Greek literature. He made the boy read Homer and was fond of soliloquies—often continuing to talk long after Pico had dozed off.

“When Grindel was sober and not in one his moods, he would discuss all sorts of subjects with Pico just as if he was a grown man.”

And then there was Old Angus, a former British soldier who served 21 years in the Black Watch, mostly in Africa. When Worthington knew him, he was a foreman on the smelter furnaces and full of blood-and-guts campaign stories from the Mahdist War in Sudan in the late 1880s.

“Old Angus was a walking book of knowledge and strangely he liked to talk to Pico on most any subject,” Worthington wrote fondly. “Between Grindel and Angus, Pico learned a good deal, and read a good deal more.”

Instead of a soccer pitch, his part-time playground was a rail yard where gangs of children dispensed their own brand of frontier justice against bullies and other wayward souls who stepped out of line. The boys often ran the risk of angering the railway men who allowed them to exercise their imaginations amid hundreds of tonnes of moving steel.

“If your teeth hit the

wrong place, the

detonator would explode

and blow your head off.”

Pico found work as a water boy in a local iron smelter where—writing more than 60 years later—his recollections of the back-breaking labour and dangerous conditions remained fresh, vivid, almost searing.

“Some days the atmosphere would be very ripe with sulphere [sic] fumes mixed with a very fine sort of flue dust that got into everything. This dust when it got into open cuts would cause them to fester. Men working around the furnaces wore goggles and nose respirators, otherwise they could not have stood it.”

It was a brutal life. Practical jokes among the smelter workers included hooking hot electrical wires to the metal water dispenser to jolt the gullible. Live lizards were also dropped down the shirts of unsuspecting newcomers.

The boy eventually took a job in the mine itself. It was dirty, dangerous work. He had to handle the detonators and explosive charges used to blast the rock face.

“You had to be careful in clamping down, if your teeth hit the wrong place, the detonator would explode and blow your head off,” Worthington recalled. “After lighting the fuse with a match, everybody would get out of the way. One thing to do was keep your mouth open so that the explosion would not hurt your ears. After the explosion and the gases cleared, the next job would be to load the cars and get the ore to the shaft.”

He learned early the capriciousness with which death could arrive. Nitroglycerin was used to blow open patches of sunbaked ground so water wells could be dug. One time a can was left at the side of a path by a careless and forgetful survey crew. Worthington was nearby when a boy and a donkey happened along the trail. The boy casually took a swing at the can with a stick.

“There must have been quite a lot of nitro in the can because the boy and the burro disappeared off the face of the earth except for the hind leg of the burro and some bits and pieces of the boy,” Worthington recalled. “That stopped kids from whacking tin cans for a while.”

Pico had friends. One rich—Henri—and one poor—Antonio.

Henri was the son of an exiled Spanish nobleman and a dignified Hungarian woman. Their home on the edge of town was large and luxurious with a menagerie of pets, including a screeching macaw and a mischief-making monkey named Jocko who was “full of evil joy.” Henri would eventually leave to be educated in Europe.

Antonio’s father had died working at the mine. The family lived in “Tin Town,” a slum on the edge of the city where people built their own homes out of the scraps they could find. Antonio’s mother worked as a washerwoman, taking in laundry.

At first, Worthington considered Antonio to be “a loud-mouth looking for a fight.” That was until Antonio stood up for a smaller boy who was being bullied. His friend, Worthington thought, seemed destined for a life—and perhaps even a death—in the mine.

Both of his friends looked at Pico with curiosity and likewise, he at them.

“It seemed to Pico that their lives had been mapped out for them,” wrote Worthington. “They also seemed intrigued that Pico did not know what he would [do with his life]…. Pico did not know what he wanted to be when he grew up, but he knew he didn’t want to be a smelter man or a miner, or a shopkeeper, or the like. He knew full well he would not stay in one place like he was and be as isolated, as if on the moon.”

You can’t help but be struck by the undercurrents of loneliness stitched within his narrative voice in the manuscript. The feeling is achingly present when Worthington wrote about a dog he adopted; a beaten-up pit-fighting dog that didn’t know how to hunt, point or retrieve, “but he always liked to go out with Pico.”

He christened him “Bulldog” and the two became inseparable.

“He never walked in front of or behind Pico, but always by the side,” Worthington recalled. “They became good firm friends.”

The story of the dog’s demise was poignant. After disappearing for several days, Bulldog returning “all chewed up,” and Worthington could see his companion was suffering. He borrowed a pistol and asked some men if they would shoot the dog. They refused.

“One man said: ‘Kid, you’ve got to do yourself. You’re his friend and he would not want a stranger to do it.’ The old dog looked up at Pico and they both knew the man was right.”

Worthington’s recollections are sprinkled with piercing social commentary that, surprisingly, would not be out of place more than 115 years later.

There were those in the town who could not understand the relationship between an eccentric English scholar, a vivacious Mexican woman and a Scottish orphan, all of whom lived under the same roof like some strange little family.

People would see them drink their coffee together, without cream and sugar at Grindel’s insistence, and marvel as all of them, the boy included, would smoke long, thin cigars.

“The good people—Gringos—would shake their head at this, set up and declare that Pico was on a downward path and so on. But they never raised a hand to help the little boy and if they had done so, Pico would not have left Grindel for anything.”

In the end, it was Grindel who left Pico.

The lure of gold in the hills beyond the desert drew the old Englishman and another man away for what was only supposed to be a “quick trip” before a full prospecting party was organized.

“They never came back,” wrote Worthington.

The bodies of Grindel and his companion were found weeks later in the desert and shortly thereafter “an austere man” from England came and gathered up all of the dead man’s papers and effects.

“Pico knew it was time for him to go,” wrote Worthington. “He had saved some, so he quit his job, packed his few belongings [in a] straw suitcase, bought a ticket to Guaymas (a port city in northwest Mexico), boarded a stagecoach and left, never to return.”

He was surprisingly generous in

his recollection of Pancho Villa.

There is a humanity in Worthington’s writing that transcends generations, in that he found sympathy and eventually common cause with the indigenous and Mexican people.

“There was a Yaqui Indian who always helped out Pico,” he wrote. “There was a saying then, one Gringo would do the work of three Mexicans and one Yaqui would do the work of three Gringos. There was a lot of truth to that.”

The social, economic and political injustice of the time made a searing impression on the boy. And it still electrified the old man who wrote decades later.

“The Mexican government of the time tried to follow the American system of putting these people on a reserve so the rich land grandees could get the fertile land. This led to war.”

Long after he had left Nacozari, Worthington “saw some of these Indians who had been captured” and were, as he told it, being sold.

“Officially it was not slavery, but the plantation owners paid the government for their hire,” he wrote. “Each Indian had to accomplish an amount of work daily that was totally impossible to do. So, every day he fell behind and would never be free again. This was the main reason Pico joined the insurrectors [sic] to fight in a war against the Mexican government…. You will be glad to know they won the war.”

The rebellion against the Mexican government was “with good cause,” he wrote, and at one point he even seemed to sneer at the hypocrisy of nations that claimed the moral high ground and were—at that time—exploiting Mexico’s resources and people. He was even surprisingly generous in his recollection of Villa and appeared to harbour no resentment for the murder of his half-brother.

His sympathies clearly lie with the poor and forgotten and the revolutionaries whom he would, in time, join in rebellion—an insurrection where Villa was a prominent figure.

“His hideout was in the Sierra Nevadas and said to be inaccessible,” wrote Worthington. “He was a very romantic figure and although he was said to be responsible for the murder of Pico’s brother, Pico took a rather philosophical view.”

Worthington’s grandchildren both reflected on the reference. Linnet Fawcett said she doesn’t “think there was any love lost between his half-brother and himself” and that his view was tempered by the wider social landscape and his subsequent experiences.

“His half-brother was a ‘Gringo’ engineer at the mine, and my sense is that Pico aligned himself more with the common workers, the Yaqui, and the Mexicans,” she said. “These allegiances perhaps drew him to the ‘Robin Hood’-style of bandit, robbing the rich to help the poor.”

Matthew Fawcett said his grandfather was fairly pragmatic and non-judgemental, and those qualities shine through in the manuscript.

“He probably had some understanding of Mexicans who became bandits and the grey line between a bandit and a revolutionary soldier,” he said.

“I never felt like a Canadian until Vimy. After that, I was Canadian all the way. We had a feeling that we could not lose, and if the other Allies packed it up we could do the whole job ourselves.

—F.F. Worthington quoted in Vimy! by Herbert Fairlie Wood

In the years immediately after leaving Nacozari, Worthington served in the Nicaraguan Army in a conflict with El Salvador and Honduras; spent time at sea working on cargo steamers; and was arrested for running guns into Cuba in 1908. He returned to Mexico in 1913 and joined the revolution led by Francisco Madero, which began in 1910.

Villa was one of Madero’s important commanders, but later fell out of favour and was driven into hiding in the U.S. But the exile was short-lived. Villa returned to avenge the assassination of Madero and his close personal friend Abraham González, governor of the state of Chihuahua, an event that touched off another wave of revolution.

Worthington was wounded in the service of the revolutionaries in 1913, the seminal year when Villa raised his famous mercenary, División del Norte (division of the north) and went on to win a string of important military victories.

The manuscript does not touch on those extraordinary events, only Worthington’s time in Nacozari. There was, however, clearly more tucked within the recesses of his memory. Perhaps he simply ran out of time.

“You realize these items come to my memory, only because I have been thinking back,” Worthington wrote to his daughter Robin as the stories took shape on the page. “They do not come as a flash but as a gradual image. Often, I am not sure of the time or sequence…. In trying to remember, further details emerge.”

Matthew Fawcett thinks it’s likely that the ambitious, independent, creative man—the non-conformist who would later be lionized within the Canadian Army—was shaped by the remarkable characters and experiences of that lonely time of self-reliance in northern Mexico.

Linnet Fawcett said she believed “it stopped him from seeing things in black-and-white terms—made him aware of, and sensitive to, the grey zones in every person and situation.

“I think, as a child negotiating that harsh, often brutal, world of colourful ‘outcast’ characters on his own and on his own terms, that he learned early to see goodness where others wouldn’t necessarily see it, and see hypocrisy for what it was.”

By the time Worthington quit the Mexican revolution, the world was on the cusp of the Great War, where the war-fighting skills and survival lessons of his unconventional childhood would be tested in the trenches of Flanders.

In 1915, he joined the Black Watch Regiment in Montreal. Becoming a Canadian was not what he originally intended. That, however, is another interesting story.

Worthy of Mention

Frederic Franklin Worthington had an eventful life after Mexico:

• enlisted in the Canadian Black Watch in 1915

• served in Canadian Machine Gun Corps in 1917

• awarded the Military Medal for action near Vimy Ridge on Jan. 6, 1917

• trained on armoured fighting vehicles at the Canadian Armoured Fighting Vehicle School at Camp Borden in 1930

• made commandant of the school in 1938

• purchased 265 WW I-vintage M1917 tanks from U.S. for $120 each

• commanded the 1st Canadian Tank Brigade in WW II

• converted the 4th Canadian Infantry Division to an armoured division

• relinquished command of the 4th Armoured Division when Lieutenant-General Guy Simonds took command of II Canadian Corps in 1944. The officially reason was poor health, but unofficially, he was edged out.

• returned as CO of Camp Borden in 1944

• made head of Pacific Command in 1945-46

• made civil-defence advisor to the Minister of National Defence in 1948-58

• died in Ottawa on Dec. 8, 1967

• interred with his wife, Clara (Larry) Worthington, in Major-General F.F. Worthington Memorial Park—also called the Tank Park—at CFB Borden

• established the Worthington Trophy, originally awarded to the best CAF reserve armoured unit and now to regular force units

Advertisement