Canadian General Roméo Dallaire. [Ryan Remiorz/Canadian Press]

The mission was a disaster.

In January 1994, Dallaire alerted the UN that an aircraft loaded with ammunition and weapons had landed—and he had learned it was intended for use in an attack on the Tutsis. He asked for permission to seize the cargo.

Permission was denied. That would exceed the mandate of the mission, he was told. For the next two months, Dallaire repeatedly informed the UN the situation was growing more dangerous; weapons were being stockpiled by Hutu extremists in the government and refugee Tutsis had formed a rebel force.

The powder keg was lit on April 6, 1994, when an aircraft carrying the Rwandan president was shot down. That night Rwandan Armed Forces and Hutu militia went house to house killing Tutsis and moderate Hutu politicians.

But this was not war; it was genocide.

Dallaire pleaded to intervene but was reminded that UN regulations allowed the use of force purely for self-protection. Dallaire ordered 10 Belgian peacekeepers to protect the new Rwandan prime minister; they were taken hostage and murdered.

The site in Kigali, Rwanda, where 10 Belgian soldiers were killed in 1994 is now a memorial. [Wikipedia]

But this was not war; it was genocide.

On April 21, the UN Security Council voted to withdraw most of its 2,500 troops. Dallaire and the 270 peacekeepers who stayed behind concentrated on saving what lives they could, and were later credited with saving more than 30,000 people.

Meanwhile, death squads hunted openly. It is estimated that more than half a million Rwandans were massacred over 100 days, many hacked to death.

In the face of international condemnation, the UN Security Council agreed to send a second force. Five hundred UN troops arrived in June, this time with authorization to enforce peace.

The madness subsided in July as a new president assumed office and committed to the peace accords. By then as many as 800,000 Rwandans had been killed and two to four million more had become refugees.

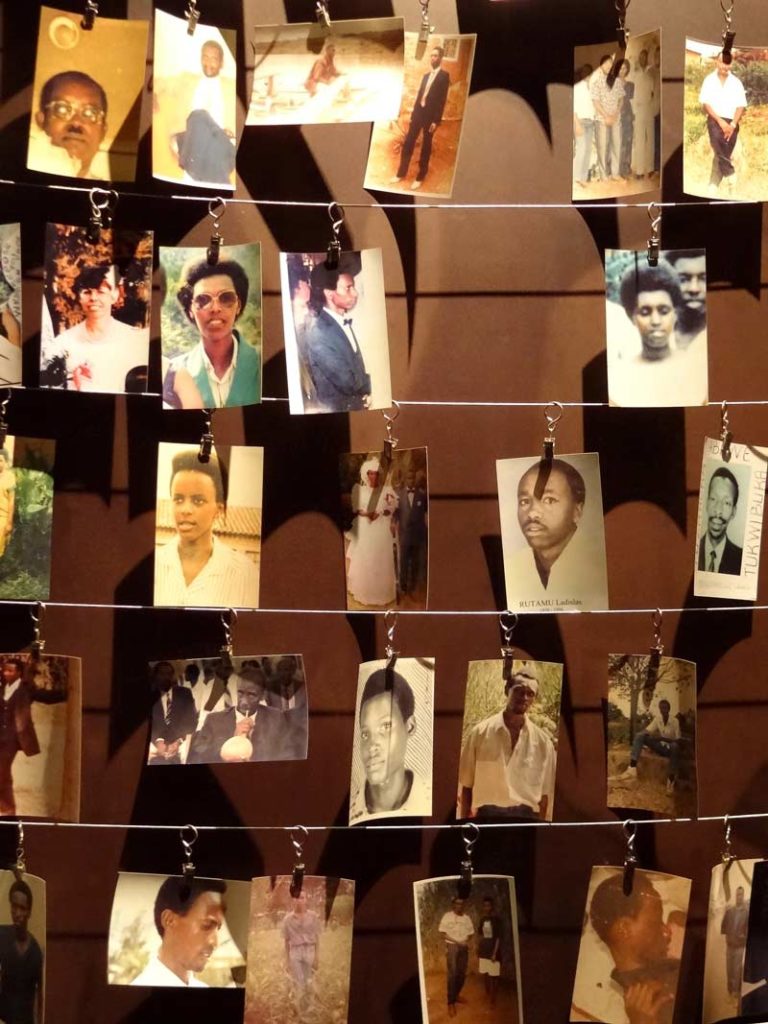

Photographs of genocide victims are displayed at the Genocide Memorial Centre in Kigali, Rwanda. [Wikipedia]

Scarred by what he had witnessed and wracked with guilt, Dallaire suffered post-traumatic stress disorder and attempted suicide. He was medically released from the Canadian Armed Forces in 2000.

Since then, he served in the Senate from 2005 to 2014, and has spoken and written about genocide, PTSD and suicide and has campaigned against the use of child soldiers.

In 2007, he founded the Child Soldiers Initiative, from which evolved the Dallaire Institute for Children, Peace and Security at Dalhousie University, which trains people how to defuse confrontations with child soldiers and rehabilitate them.

The institute collaborated with the Canadian Armed Forces to create the Dallaire Centre of Excellence for Peace and Security in 2019.

Advertisement