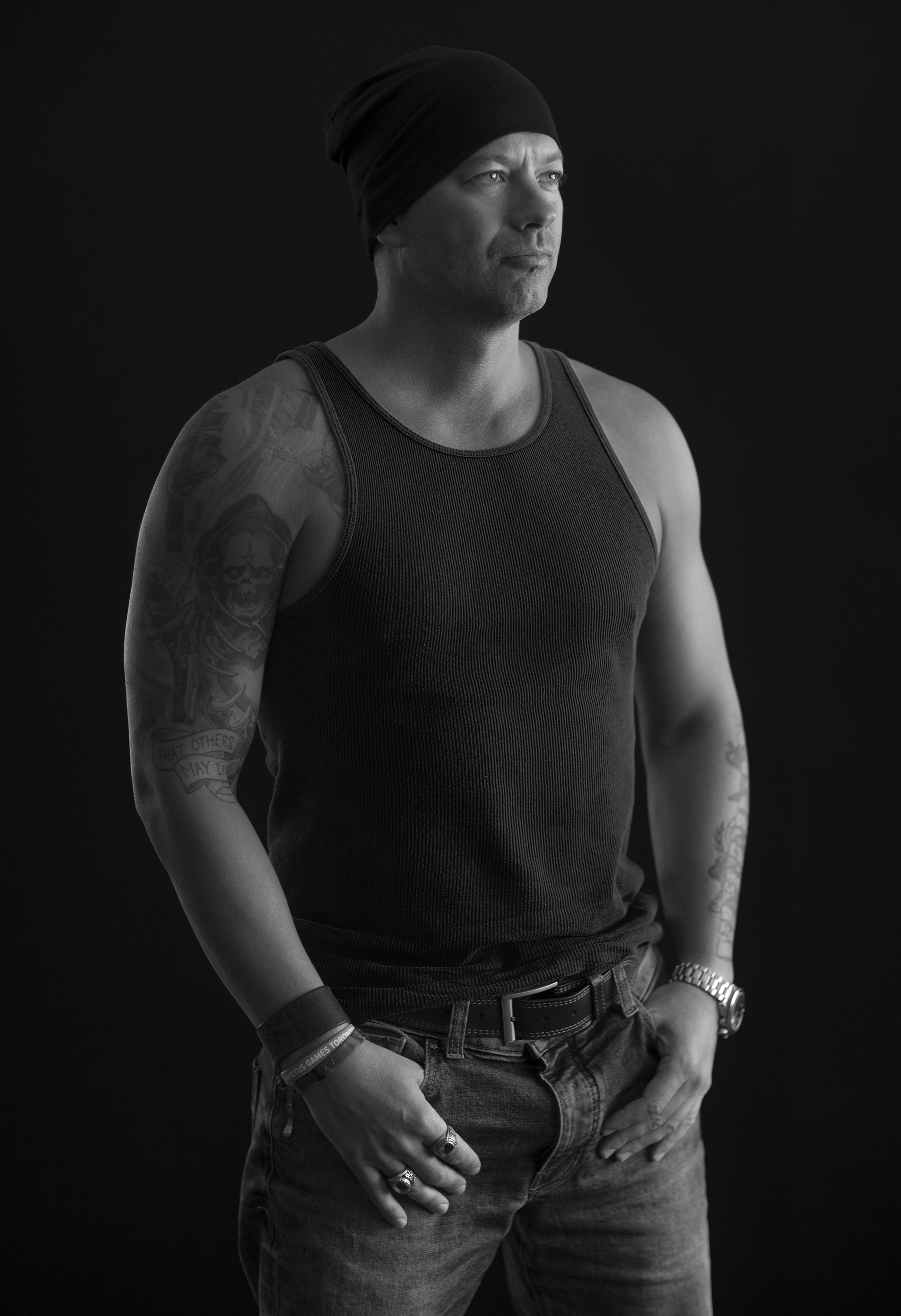

Nic Meunier keeps asking himself that: If you take one,

how many must you save to make up for it?

Story and photography by Stephen J. Thorne

“If you take one life and save one life, it’s not the same,” says Nic Meunier, who reached the peak of the soldiering trade before becoming a search-and-rescue technician (SAR Tech).

“If you see one person die, you might have to save like 10, or 20, maybe 100. I don’t know how many you have to save. At some point, you want to have karma balance. I wanted to save as many people as I could.

“I lived half my career with the guilt of doing bad stuff. It’s what brought me to search-and-rescue. I was tired of seeing people dying all the time.”

The Montreal native has probably saved hundreds—on and under water, in ice, in the bush, beneath rubble, on the battlefield. He doesn’t have a tally.

“I remember the people I saved, but I probably remember more the ones who died.”

And despite the lives he saved, karma seemed to catch up with Meunier, again and again.

Continued from Military Health Matters e-report No. 5

The SAR Tech community is a small one—just 125 members, including operations, training and administration, at five bases across the country. A third are seriously injured each year, one will die; all will fall to serious injury over a four-year cycle.

Meunier saved many lives, but he paid a price. His injury rate was extraordinarily high. A veteran of many missions he can’t discuss (more than 50 he describes as traumatic), he’s been shot, broken his back, compressed three discs, broken arms, broken ankles, dislocated shoulders and torn ligaments. Doctors replaced both his knees with titanium; his left ankle has been fused.

Now, Nic Meunier is waging a titanic battle for his own life after a free-diving rescue on a shipwreck off the British Columbia coast. He saved two crew members and recovered the bodies of two others, but it exacted a huge toll on the robust SAR Tech team leader.

He repeatedly inhaled battery acid that had formed in an air pocket between the boat’s overturned hull and the waterline. Soon after the mission ended, Meunier started vomiting, coughing up pink chunks of lung and passing out.

After treatment, Meunier went on one more mission—and saved one more life. Then he was diagnosed with stage 2 lung cancer. He lost a third of his left lung to surgery in August, endured many radiation treatments and months of chemotherapy.

After a 21-year career, he had calculated that by studying and moving up the ladder to co-ordinating missions, he could save even more lives. For the first time in years, he had been finding some inner peace, escaping the demons of guilt and post-traumatic stress. Meunier had earned a master’s degree in disaster and emergency management at Royal Roads University near Victoria. He was a PhD candidate, 37 years old, and then suddenly, after a 20-year career, he was sick and no longer in the Canadian Armed Forces.

He lost friends, relationships, 40 pounds and his self-esteem.

“You’re not yourself when you’re on so many medications,” he says. “You don’t trust anything. Suddenly, you’re not good enough anymore. You’re depressed.

“When I took my retirement, I lost my identity. You lose your culture. You lose who you’d been since you were, in my case, 16 years old and even before that. People compare it to losing a child. All my PTSD came back, worse.”

Friends who weren’t physically injured, faced similar trauma. Some committed suicide—one in front of him and another while on the phone with him. His saving grace was sports. He medalled in archery at the 2016 Invictus Games.

As he neared the end of his chemo regimen, Meunier recalled his first mission after an intensive couple of years of training. He helped rescue 32 children from a burning boat. As he left the emergency ward covered in blood, weeping parents looked to him in desperation. He smiled and told them their kids would be okay.

“They grabbed me and hugged me and thanked me,” he recalls. “That’s the best thing of my life. You savour that. You feel that inside peace from all the bad stuff.

“You appreciate that moment more than anything. That’s the real reward. No SAR Tech is doing it for the money. Nobody’s doing it for recognition or a pat on the back. It’s just that look from the parents when you bring their kids back alive.”

To view more images and read other instalments in Stephen J. Thorne’s Portrait of Inspiration project for Legion Magazine, please click below.

Advertisement