Wallace Rupert Turnbull during a propellor test at Camp Borden, Ont., in June 1927. [Parks Canada/National Research Council]

After graduating as a mechanical engineer in 1893 and studying physics in Germany, Turnbull started testing aircraft stability and the efficiency of various wing designs in his Rothesay workshop, which included Canada’s first wind tunnel.

During his research, he conferred with renowned innovators Alexander Graham Bell and Wilbur Wright as they worked to get their respective planes airborne. The results of his experiments were published in aeronautical journals, including a seminal piece in 1909 on propellers.

The First World War interrupted his research, however, and Turnbull went to England to design propellers for military aircraft. There, he began working on a mechanism that would allow a plane’s pilot to control propeller pitch, akin to shifting gears in a car, which would ultimately make the plane easier to fly.

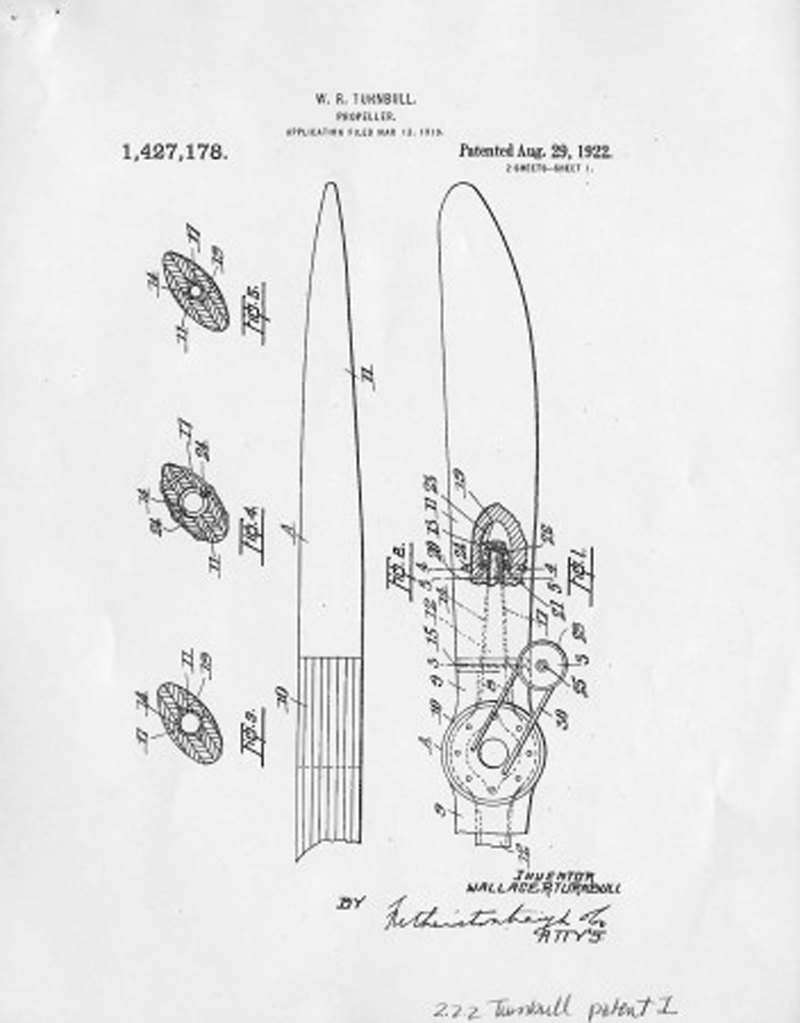

Turnbull’s design was patented in 1922.

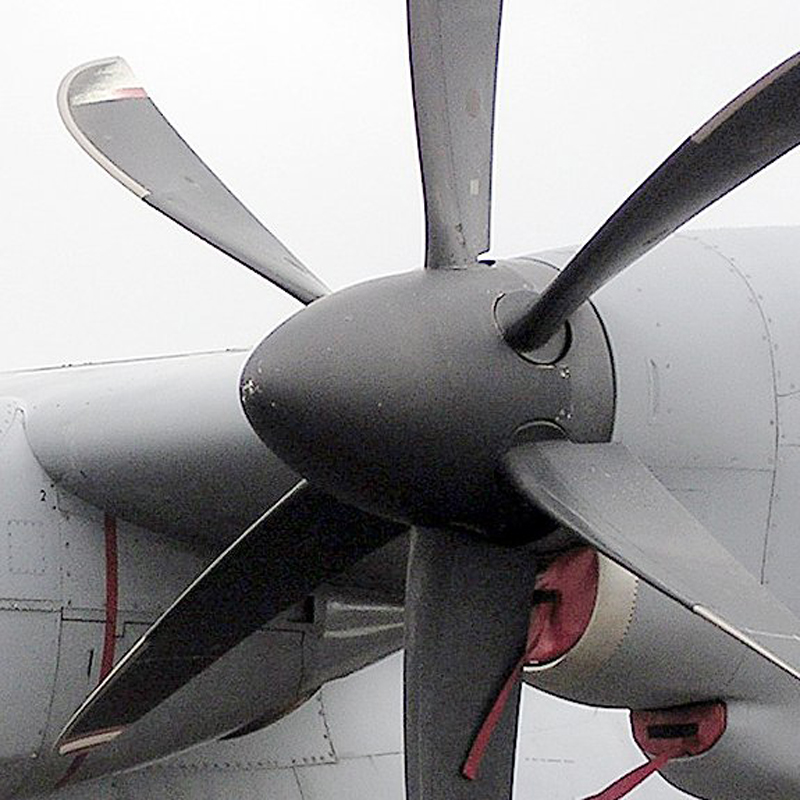

Fixed-pitch propeller blades were sufficient when planes flew slowly at low altitudes, but they were inefficient at faster speeds and when taking off or climbing. A variable-pitch propeller, however, could be adjusted during flight to produce maximum thrust in these situations.

The concept had been around for decades, and various designs had been tried, but they wore out too quickly to be economical on aircraft with big engines.

While others tried designs for hydraulic mechanisms that required engine modifications to provide the oil to power them, Turnbull developed a method that used an electric motor to vary the prop’s pitch.Turnbull’s design was patented in 1922. The Royal Canadian Air Force conducted the first test flights using the mechanism on an Avro 504K at Camp Borden, Ont. In June 1927, it was declared a success. That plane, with its variable-pitch propeller, is now in the collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum.

Two years later, Turnbull sold the patent to U.S. aviation company Curtiss-Wright.

During the Second World War, Curtiss-Wright produced nearly 150,000 variable-pitch propellers for the Allied cause.

In the 1930s, the first Boeing 247 commercial passenger plane had variable-pitch propellers and soon other airlines were installing them to take advantage of better control during takeoffs and landings and improved performance while climbing and cruising.

During the Second World War, Curtiss-Wright produced nearly 150,000 variable-pitch propellers for the Allied cause.

“Today, variable-pitch propellers are common to virtually all propeller aircraft,” wrote Dwayne A. Day in an article on centennialofflight.net.

“It is not unusual to see commuter prop planes at an airport parked with their propellers rotated forward, ‘feathered’ so that the pilot can start spinning the propellers on the ground without generating thrust. This is barely noticeable, but challenging technological innovation plays a major role in improving the aircraft’s performance.”

Turnbull’s innovation garnered him the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain’s bronze medal and induction into Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame. Still, few Canadian air passengers today recognize his name or know the significance of his invention to modern air travel.

Advertisement