Parks Canada archeologist and co-author of Evidence for European presence in the Americas in AD 1021, Birgitta Wallace. [B. Wallace]

“We don’t know how long before and after they were there.”

A co-author of a groundbreaking study that pinpointed Viking activity in North America to the summer of 1021 AD says Norse explorers likely arrived at the Newfoundland site years before they cut the wood on which the finding was based.

Longtime Parks Canada archeologist Birgitta Wallace, one of the world’s foremost experts on Vikings (Norse) on this continent, said the finding using a new form of radiocarbon dating may well represent the last year the Norse explorers spent at L’Anse aux Meadows on Newfoundland’s Great Northern Peninsula.

“It’s slightly later than we would have expected,” Wallace said in an interview with Legion Magazine. “We have one date, but we don’t know how long before and after they were there.

“From the archeological data, I would say they were not there much longer. This could well have been about the last year that they cut that wood.”

She plans further investigations to see if the theory holds up.The method of high-precision accelerator mass spectrometry that nailed down the date had only been used once before—a test of sorts on artifacts from a Russian site whose age had already been significantly narrowed.

At L’Anse aux Meadows, scientists identified specific rings in three pieces of cut wood that, due to the presence of elevated levels of carbon-14, could be directly linked to massive solar flares that are known to have occurred in 775 and 993 AD.

Wood artifacts the scientists studied to determine the exact date they were used by the Vikings. [G. Vandervloogt]

The wood, from two fir trees and one juniper, could only have been harvested by Norse who sailed from Greenland because the characteristically clean, low angle-in cuts showed that all the pieces had been taken by metal tools that were unavailable to the area’s Indigenous inhabitants at the time.

While the precision of the new technology and the uniformity of the samples stunned the researchers, the actual findings were of little surprise.

“All it does tell us, really, is that they were there in 1021,” said Wallace, who has worked at the site periodically for close to 60 years and produced multiple journaled articles on its role and the movements of its inhabitants. “If you ask them in Iceland, they’ll say ‘we have known that since the actual events.’ They were not interested in Columbus.”

In Norway and her native Sweden, where Wallace grew up fostering her passion for the past by visiting ancient sites and museums with her father, interpretations of Icelandic sagas were translated in the early 1600s. The Vikings’ wanderings into North America, or Vinland, were originally part of oral histories first put to vellum (calf skin) in the 13th century.

Furthermore, archeological study has long dated their presence on these shores to centuries before Columbus. Thus the range of Norse exploration has long been taken for granted throughout Scandinavia and much of academia.As for their time in Newfoundland, Wallace bases what she calls “a hunch” on periods of occupation at L’Anse aux Meadows, identifiable by the thin deposits that exist between them. The 1021 artifacts came from the top, or most recent, layer.

About 100 Norse, men and women, are believed to have occupied the site off and on over a period spanning between three and 13 years. Wallace’s findings establishing the settlement as a base for further wanderings, some southward, are now widely accepted.

Wallace spent about a quarter of her career at Parks Canada on Viking research. She says she waited years before reading the sagas because she wanted to see what the archeology of L’Anse aux Meadows had to say. It said a lot.

The site at the very tip of the Great Northern Peninsula was markedly different from the Norse farms in Iceland and Greenland, she said.

“At L’Anse aux Meadows, there were no barns or stables or any kind of enclosures for cattle and sheep, which occur in all of the Icelandic and Greenlandic sites,” she said. “Instead, we found very specialized activities.

“There was one group that cut wood and did carpentry. Another group smelted iron and made iron. And another group tended to boat repair.”

Boat repair was identifiable by discarded cut nails that would have been rusted, removed and replaced. “We found quite a few at L’Anse aux Meadows.”

“The people who had been at L’Anse aux Meadows had been farther south.”

Her teams also found different types of slag related to ironmaking and ironworking, readily discernible to metallurgists. The advantage of working with Parks Canada, she said, was the access the archeologists were given to specialists and the freedom they had to thoroughly analyze their finds with novel methods and technologies.

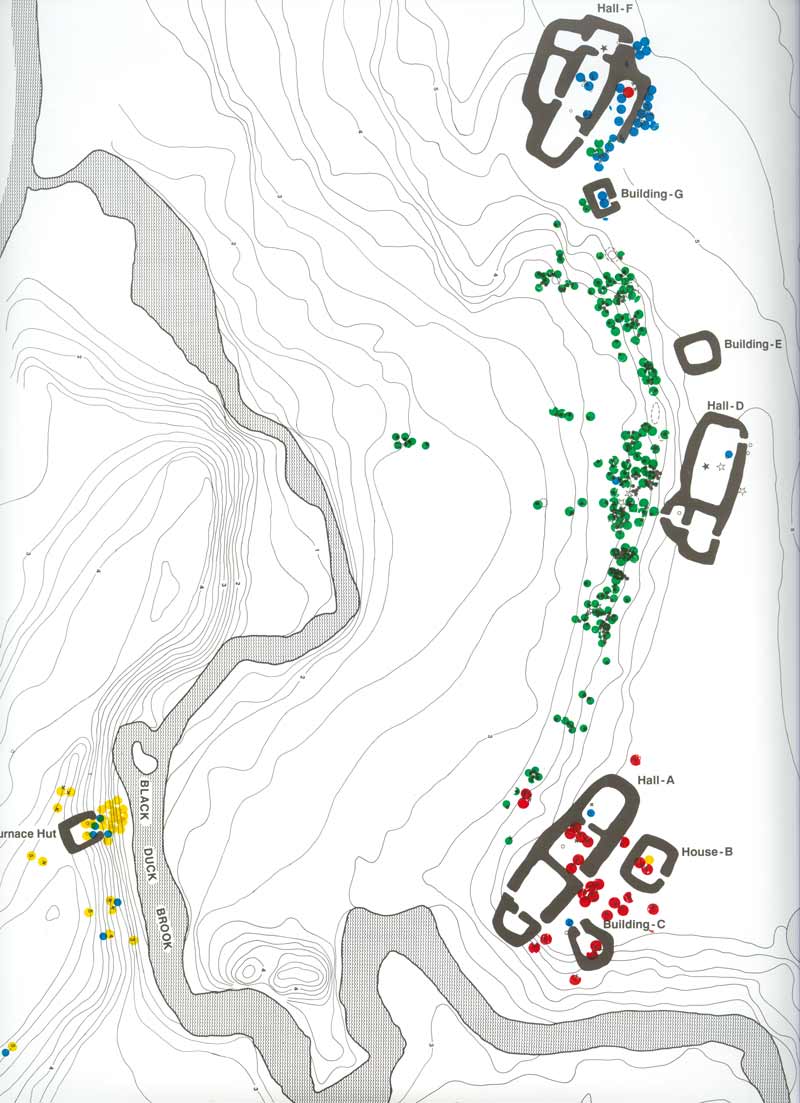

The yellow dots represent iron smelting slag, the red dots represent smithing slag, the green dots represent wood and the blue dots represent clipped-off iron nails. [B. Wallace]

Her discoveries, for example, have included seeds from butternut trees, whose northern range ends in central New Brunswick. “We realized then that the people who had been at L’Anse aux Meadows had been farther south.”

Grapes were a big deal to the Vikings—“Vinland,” after all, is Old Norse for “land of wine.” Wine grapes, she would come to learn, figure heavily in the Icelandic sagas. Quality hardwood, too, was a coveted commodity for ships and buildings.

“Newfoundland has birch but that’s not always so useful for building,” said Wallace, who first worked at the site with its discoverers, the husband-and-wife team of Helge and Anne Stine Ingstad, in 1964.

Norwegian archaeologists Anne Ingstead and her husband, Helge, discovered the norse settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows in the 1960s. [Wikimedia]

She figured it was the wood the explorers set out to find, and the grapes were a happy accident.

It was then that Wallace turned to the sagas and analyzed them “in much the same way that you would an archeological site, such as what kind of people were there, how long were they there, what were they doing, what kind of resources did they zero in on.”

She found striking parallels between Icelandic sagas and the writings of French explorer Jacques Cartier on his first voyage to North America 500 years later that describe the landscape, vegetation and peoples around New Brunswick’s Bay of Chaleur.

Wallace noted that Ólafur Halldórsson, a specialist on the Icelandic medieval manuscripts at the Árni Magnússon Manuscript Institute in Reykjavik, has said that “if you didn’t know that Leif Ericsson could not have read Cartier, you would think that he had.”

“You have to be willing to change your opinion or ideas.”

There have been findings suggesting Vikings ventured as far as the northeastern United States.

The Halifax-based Wallace, 77, believes that technological advances, such as the one that nailed down the date at L’Anse aux Meadows, will advance the field of archeology by leaps and bounds, altering the history we thought we knew.

“You have to be willing to change your opinion or ideas as soon as something new comes up,” she said, predicting much more will be learned about Vikings in North America and elsewhere.

Parks Canada hired Wallace away from the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in 1975. Fascinated by prehistory since she was five years old, she “retired” years ago but continued working under contract to the agency. She writes and has organized Viking-related exhibitions for museums, including the Smithsonian Institution.

Advertisement