Captain William Arthur Peel Durie died near Hill 70 in France in late December 1917. [LAC]

Three years later to the day of Captain William Arthur Peel Durie’s death, a soldier wrote Durie’s mother Anna to tell her details of how “Bill” died as he made his way along the communication trench a half-hour into the attack.

“In December we were ordered to the Trenches in a very wicked part of the line just North of ‘Lens,’” W.H. Edwards wrote in 1920, “and on December 29, 1917, the ‘Hun’ placed a very heavy Gunfire ‘barrage’ on our front, resulting in Bills’ [sic] men catching it very heavy.

“As usual, he was out in it all, encouraging his men, when he could have been lying in his dugout under cover, but not him, out he went, collected the few men left, and stayed with them, until his sergeant remonstrated with him to get below, he refused to leave and was struck down, resulting in the loss of the biggest man the Battalion ever had.”

Reports said he died instantly. Shortly after, 20 Germans emerged from the trench opposite and began an advance.

“Party was preceded by 2 scouts about 20 yards ahead,” reported Dougall, a 32-year-old farmer who would end the war with a Military Cross and bar, along with a Distinguished Service Order and bar, and two Mentions in Dispatches.

“Our trench at this point was not well manned but party was dispersed by Sgt. [Joseph] Hardy, who shot the two leaders with his revolver and Lieut. Horton, who turned a Lewis Gun on the remainder.”

The Germans dropped 200 cylinders of gas on the Canadian line at 4:30 the next morning, wounding seven more members of the 58th. An explosion wounded six others.

Arthur was buried in a hastily dug battlefield grave at what would become Corkscrew (Bully-Grenay) British Cemetery, France.

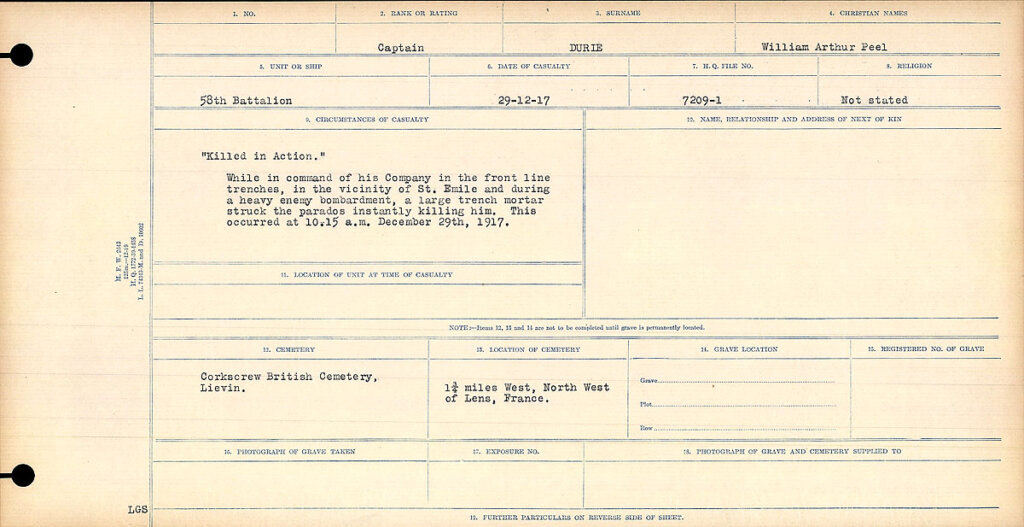

Captain Arthur Durie’s Circumstances of Death register reads, “While in command of his company in the front line trenches in the vicinity of St. Emile and during heavy bombardment, a large trench mortar struck the parados instantly killing him. This occurred at 10:15 a.m. December 29th, 1917.” [LAC]

Bodies of those whose families could afford it were sometimes shipped back for burial in their hometown cemeteries.

The body of at least one Canadian, Captain Robert Clifford Darling of the 15th Battalion (48th Highlanders), who died of wounds in England on April 19, 1915, was officially repatriated to Canada and buried in Toronto’s Mount Pleasant Cemetery.

When Fabian Ware learned that official records weren’t kept after he volunteered with the Red Cross to record the location of British burial sites in 1914, he took steps that led to the creation of the Graves Registration Commission.

An over-aged Ware would become a British army major-general, and the commission would evolve into the Imperial War Graves Commission. Now the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, it cares for the graves of about 1.7 million Commonwealth war dead in more than 23,000 separate burial sites and memorials worldwide.

In April 1915, the commission established a policy of “equality of treatment after an equality of sacrifice.” The order prohibited exhumations for repatriation on grounds of hygiene and “on account of the difficulties of treating impartially the claims advanced by persons of different social standings.”

Besides the issues of hygiene and fairness, there was the matter of the war itself. The Great War—the war to end all wars—was the first industrialized war, a war in which refined versions of the machine gun were ubiquitous, artillery more mobile and accurate, and airplanes a weapon that opened whole new avenues of warfare.

Military tacticians were slow to adapt to the new realities, and wholesale slaughter as troops poured over the top and across no man’s land in the face of withering machine-gun and artillery fire was common. There were more than nine million military deaths in WW I.

It was, for all intents and purposes, industrialized slaughter. Commonwealth countries alone lost more than 1.1 million uniformed military between 1914 and 1918, some 66,000 of them Canadian. Repatriating the dead was out of the question.

“As usual, Arthur was out in it all, encouraging his men, when he could have been lying in his dugout under cover.”

Anna Durie couldn’t accept this and in June 1921, she and Helen went to France with the intention of bringing Arthur’s remains home to Canada, by hook or by crook.

Local commission officials tried to restrain this “quite unreasonable” woman who “has practically lost her senses on this one subject,” to no avail.

In one of her many letters to the commission spanning two decades, she declared its British-born deputy controller, Colonel Herbert Tom Goodland, an American “by birth” and “not likely, it appears to me, to understand Canadian standards.” Goodland had lived in Canada for 30 years.

Unconvinced that her son’s remains were, in fact, where the commission said they were, Anna and her daughter, along with two local men, exhumed Arthur’s blanket-wrapped corpse from the Corkscrew cemetery on the night of July 30, 1921.

The quixotic Anna had apparently done an end run around the commission and parlayed a reluctant sanction for the removal from local authorities.

“With the assistance of one of the two Frenchmen who were with us, I and my daughter laid him in this oak coffin, which is lined with metal of some kind and the coffin bears a leaden plate with his name and the number of his battalion,” Anna wrote.

But as the coffin was hoisted onto a waiting cart, the horse reared and snapped the shafts. Shards of wood pierced the animal’s side. Arthur’s remains were left in the new casket and returned to the grave.

“When I exhumed my son’s body I found him only about 4 feet below the surface of the ground and now the top of his coffin is not more than 3 feet below,” lamented his mother.

As was the case with many battlefield cemeteries, remains of some Corkscrew occupants, including members of Arthur’s 58th, would later be transferred and consolidated in a more suitable location, in this case at the larger Loos graveyard.

Angry that she wasn’t informed of the transfer beforehand, convinced she had been misled, and fearful that her son’s remains were lost, Anna returned to France in the summer of 1925 and engineered an extraordinary transfer of her own.

“It is only by falsehood and misrepresentation that you could have accomplished the removal of the remains of my beloved son…from Corkscrew Cemetery,” she had written Ware, by then the commission’s vice-chair.

“It is not usual to find an Englishman so wanting in a sense of honour.”

Ware subsequently warned Goodland that the irrepressible Anna Durie was on her way to Europe and told him: “I think you had better warn people privately to be very careful how they talk to her.”

The monument on Arthur Durie’s grave in St. James’ Cemetery, Toronto. [S. Abba]

“The coffin was found to have been forced open, the timbers had been broken and the zinc shell had been cut open,” it said. “The coffin was empty apart from a few [seven] small pieces of bone and fragments of clothing.”

“I think Mrs. Durie must have bribed very heavily to have carried this out,” Colonel Henry Osborne, secretary-general of the commission’s Canadian agency, wrote in a separate memo. “The police had previously been advised of a possible attempt.”

In a last act of defiance, Anna filled out a form requesting a personal inscription for the headstone planned for her son’s now-empty grave at Loos: “He took the only way and followed it unto the glorious end.”

The request was moot. Arthur’s headstone was removed from the Loos cemetery in 1928. The location of his grave is listed on the Commonwealth commission’s website as Toronto (St. James’) Cemetery, Canada.

Bodies of those whose families could afford it were sometimes shipped back for burial in their hometown cemeteries.

The French authorities were eager to prosecute, but their British and Canadian counterparts wanted to avoid alienating a sympathetic public and arousing any lingering resentment that existed among the general populace over the repatriation ban. An internal commission report noted that “it is the view of those familiar with the case that any reopening by legal process will result in more harm than good.”

“There are other Canadians who are trying to get their relatives’ remains home,” acknowledged another commission document dated Nov. 2, 1925. “The High Commissioner’s office is uneasy on the matter.”

Indeed, the Durie saga wasn’t the only attempt by a Canadian family to repatriate a loved one’s remains from the continent. In 1919, with the consent of the prefect of Pas-de-Calais, France, the remains of Major Charles Elliott Sutcliffe were moved from their resting place at Épinoy and reburied in Lindsay, Ont.

And in May 1921, after the commission refused permission, William Hopkins, the former mayor of Saskatoon and father of Private Grenville Carson Hopkins, surreptitiously took his only son’s remains from a Belgian cemetery to a mortuary in Antwerp. They were recovered before they could be shipped to Canada. Threatened with legal action, Hopkins returned to Saskatchewan empty-handed; his local helper was prosecuted but avoided jail.

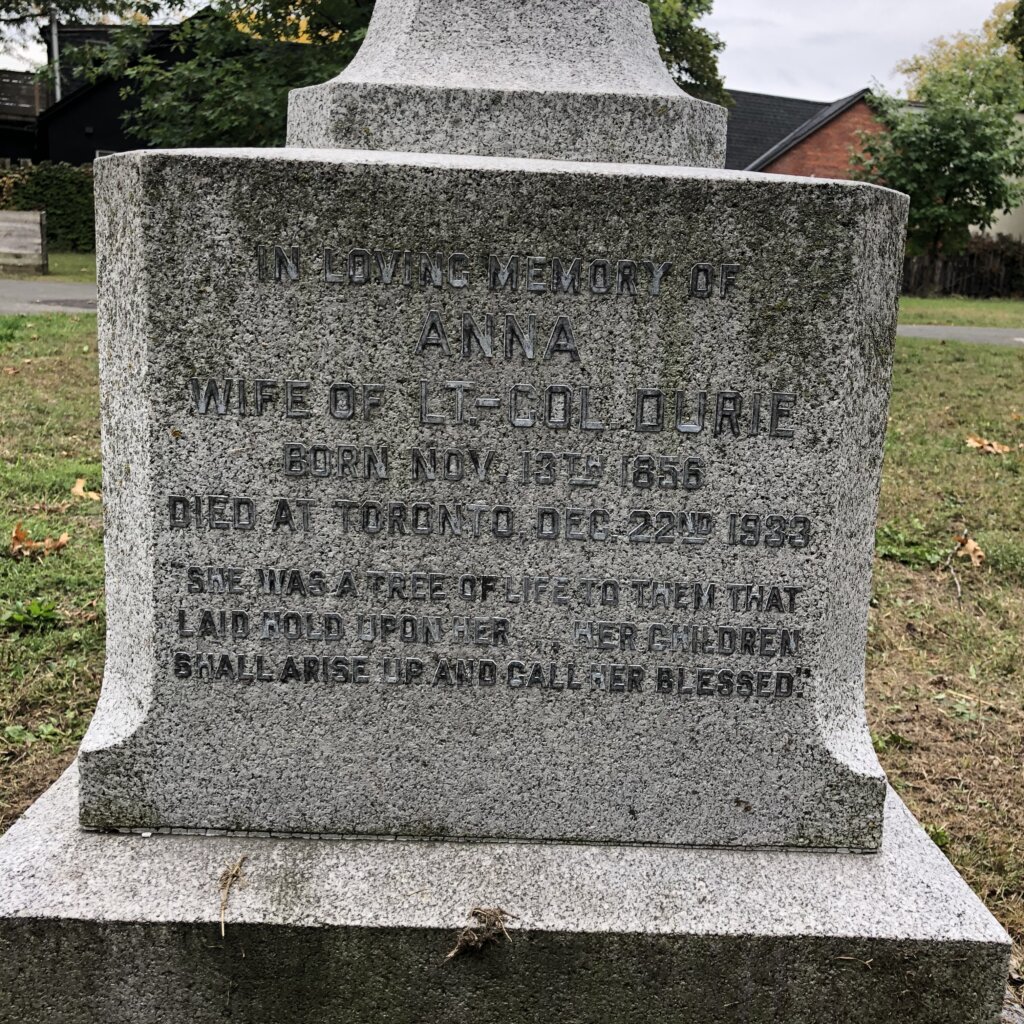

A tribute to Anna Peel Durie on one side of the monument honouring her son in St. James’ Cemetery, Toronto. [S. Abba]

“I am on the horns of a dilemma,” Ware wrote as French gendarmes continued their investigation in April 1926. “We cannot allow our cemeteries to be violated in this disgraceful way with impunity—goodness knows the dreadful things that might happen if once it becomes known it could be done.

“What the Police are frightened of is that Mrs. Durie must have made use of some organization existing in France to make money in this way and they have other evidence to this effect.

“I do not see how I can stop the course of their investigation, even if I ought to. On the other hand, from the point of view of our general policy, in our own interests and those of all decent sentiment, we ought now to leave Mrs. Durie alone.”

The commission appealed through Canadian diplomatic channels to have the case quashed.

More concerned with finding her French associates, the gendarmes abandoned attempts to interview Anna and ultimately dropped the case on March 31, 1928.

Anna never formally acknowledged to the commission the role she played in the pilfering of her son’s remains. And no body-snatching epidemic ever materialized.

The mother who wouldn’t quit succumbed to cancer in December 1933 at age 77. Her daughter Helen never married and died in 1963.

They are buried next to William and Arthur in St. James’ Cemetery. A 2.5-metre-tall cross of sacrifice marks Arthur’s plot, on which the words “he showed conspicuous bravery” are engraved.

Anna’s memorial declares her devotion as a mother and the force of nature that she was.

“She was a tree of life to them that laid hold upon her,” it says. “Her children shall rise up and call her blessed.”

Advertisement