Anna Bella Durie repatriated her soldier

son’s remains from France after WW I. [Photo: City of Toronto Archives]

In the dark of a summer’s night in 1925, four shadowy figures—two women and two men—stole into the Loos British Cemetery in Loos-en-Gohelle, France, dug up grave no. 19 in plot 20, row G, broke open one end of the coffin, dragged out the remains therein, and made off with them in a sack.

The bones were those of Captain William Arthur Peel Durie, a former Toronto bank clerk who had commanded ‘A’ Company, 58th (Central Ontario) Battalion. He had fought at Vimy Ridge, Passchendaele and Hill 70. The women were his sister Helen and his doting and, the evidence suggests, difficult mother, Anna Bella Durie.

Anna recognized the remains of the son she called her “poor darling bunny” by the boots she had bought him for Christmas just days before he died.

“I was going like a criminal, by night, to exhume the body of one of the bravest officers that ever left Canada!” she would later write.

It was July 25. The remains of Arthur, as he was known to his family, had only recently been moved from his battlefield grave at Corkscrew Cemetery close to the site of his death outside Lens. So, when the clandestine cadre returned the coffin to its resting place, with a few bone fragments and some clothing still inside, and covered it over, they left the topsoil looking much as it had.

Within days, Anna and Helen were aboard a ship sailing for Canada, with Arthur’s remains stuffed in a suitcase. Cemetery workers and officers of the Imperial War Graves Commission were none the wiser—until, that is, Toronto papers announced his Aug. 22 burial in St. James’ Cemetery off Parliament Street in Cabbagetown.

It was at least the second time Anna had tried to exhume the remains of her son after he was killed in action in late December 1917. By her previous actions and the flood of letters she had written, commission higher-ups knew her only too well and had little doubt as to who was behind Arthur’s unorthodox repatriation.

“I was going like a criminal, by night, to exhume the body of one of the bravest officers that ever left Canada!”

Arthur Durie was 34 years old when he enlisted in June 1915. His father was the late Lieutenant-Colonel William Smith Durie, first commanding officer of The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada.

Anna was 43 years her husband’s junior. They had been married just five years when he died in 1885. She would prove a formidable force—a seasoned, worldly Victorian-era military wife and fervent mother who wasn’t about to take any guff from anyone, least of all army stuffed shirts and cemetery mucky-mucks.

A 2014 Toronto Star story saddled her with the latter-day title of “helicopter parent.”

Arthur barely knew his father. He was four years old when he died. Widowed at 29, his classically educated mother struggled to uphold the life to which she was accustomed.

In the 1890s, Anna lost her home and six hectares of land on Toronto’s Spadina Road. Though money was tight, she managed to send Helen and Arthur to private schools, where they were educated among Toronto’s elite.

Helen flourished at Bishop Strachan. Arthur was perpetually languishing at the bottom of his class at Upper Canada College. “Seems to work hard,” the teachers wrote, “a little slow.”

Arthur left school as a junior and by 1899 he was working at the Royal Bank.

“He likes the work ever so much better than he did at first,” Helen wrote to her grandfather. “I do hope he will succeed. He is not clever, but is exceedingly persevering, and mother and I hope that will him to success.”

He attended the Toronto School for Military Instruction in the fall of 1908 and was awarded the rank of subaltern, a British military term for a junior officer. He enlisted soon after war was declared and joined the 58th as a lieutenant.

Anna followed her son as he began his military training in Niagara-on-the-Lake, then again to England. She took up residence in a London hotel and proceeded to relentlessly petition British, French and Red Cross officials to allow her to volunteer as a nurse or anything else near the front.

Now 60, she had seen her share of conflict, including the 1862 siege and capitulation of her Irish family’s adopted city of New Orleans during the U.S. Civil War.

Her proposals were all rejected, but Anna remained in England for much of the war, active with the Red Cross and financed by Arthur’s army pay, while Helen, an English teacher, for the most part remained in Toronto.

Arthur Durie (left), his mother Anna (centre) and his sister Helen. [Photo: City of Toronto Archives]

With Arthur now residing in the mud-soaked, rat-infested trenches of the Western Front, his mother was sending him cakes and sweets from Oxford Street in London.

She also bought him a shield and helmet for nearly $20 (the equivalent of almost C$590 in 2025).

Arthur wrote letters to his mother and sister about life at the front and undisturbed parts of the countryside that reminded him of Ontario. His nerves were steadier through the shelling than they had been at the bank, he told Helen. He asked his mother not to send the helmet. He wouldn’t wear it, he said. Officers just didn’t do that.

“As you walk through the lovely country you would not know there was a war on,” he wrote from his billet “somewhere in France” on March 21, 1916. The rest of his battalion had moved to Vierstraat, in Belgium’s volatile Ypres salient, and he would be headed there soon.

“You see the peasants working away tilling the ground and it is perfectly quiet except for the occasional firing.”

Eight weeks later, three days after a major skirmish at Sanctuary Wood (nine killed, 14 wounded, six shell shocked, 12 missing), Arthur was shot through the right lung while riding with a supply column delivering ammunition near Ypres.

It was May 4, 1916. A Toronto Telegram report, with the headline HELMET SAVED HIS LIFE, reported at the time that he was also hit in the head and rendered unconscious for two days.

“One of the new steel helmets now being worn by the British soldiers at the front saved the life of Lieut. W.A.P. Durie of Toronto,” the paper reported. It said it was shrapnel from a shell burst, not a bullet, that hit him.

Whether he had relented, and it was the helmet that his mother bought him may never be known.

An Imperial War Graves Commission file indicates Durie’s remains were originally moved from the Corkscrew Cemetery to the Loos British Cemetery in France. [Photo: Canadian Virtual War Memorial]

“Lieut. W.A.P. DURIE wounded slightly,” the war diary records.

In fact, he was declared “seriously wounded” and “dangerously ill,” and hospitalized for months. Steel was still embedded deep in his chest when he was reactivated, though the documents claim that it was giving him “no trouble.”

“We had always known that Arthur would be seriously wounded that was why I was in England,” his mother confided in an unpublished manuscript of letters in the Toronto Archives.

“I had been in London a little over two months and was dressing for dinner on a lovely May evening when the Swedish maid came into my room with a telegram enclosed in one of those reddy brown envelopes that everyone in England with men at the front had learned to dread.”

Anna left for France immediately, doing her best to disregard a ban on civilians at the front. She talked her way into her son’s hospital, where she promptly began criticizing his medical care. She kept fresh fruit and flowers at his bedside.

“His breath came with such difficulty that he could only speak in gasps,” she wrote to her daughter, shocked by the blood bubbling and drooling from his mouth whenever he tried to talk.

He couldn’t lie down for 12 days. His mother followed him to a convalescent home in Brighton, England. Helen arrived soon after.

They spent many happy hours together. Mother and daughter hoped Arthur’s wound would be his ticket home. His sister couldn’t imagine a medical board clearing her beloved brother for front-line service; he could barely walk.

Meanwhile, Anna had gone behind her son’s back, finagling an audience with Canada’s minister of militia and defence, Sam Hughes.

She secured Arthur a staff position, but he refused it. Undeterred, his mother mined her London society connections and snared him administrative jobs in England and France, which he also declined.

“I do not want a job, and was very sorry you spoke to Sir Sam Hughes,” he wrote her. “I could have got some sort of a job in London, but would rather rejoin the 58th.

“Everyone knows I want to go back and I am afraid you have only done me harm,” he told his mother on Nov. 20, 1916. “I know dearest Mother, you think you do things for the best, but don’t you think you are (sometimes) a little impetuous.

“This is a battalion where all the officers and men return to their own battalions in France, and I will rejoin the 58th in due course.”

Said Anna: “Arthur was very firm: Imperial officers always returned to the front without a word of complaint, rather, with eagerness, and a Canadian could not do less.”

“His breath came with such difficulty that he could only speak in gasps.”

By Christmas 1916, Arthur was back in a “quiet spot” at the front relishing family care packages—and sending home blank cheques to pay his mother’s mounting bills. He was a popular officer; the men called him Bill.

On Christmas, he read his ‘A’ Company boys the poetry of Robert Service.

“You don’t know how strange it was to be in the line on Christmas Day,” he wrote. “We were very near the enemy; they could hear us walking through the water” in no man’s land.

But Arthur was developing trench fever and neurasthenia, a form of nervous exhaustion similar to what is today known as chronic fatigue syndrome. He was sent to recover in the south of France.

“Will you please join me there?” he asked his mother in January 1917.

Anna met him in Menton, just up the Mediterranean coast from Nice. Her letters reflect her revulsion at her son’s stories of death and corpses left rotting in the mud. Things were grim, different, she told her daughter.

“I am not going home until the war is over,” she wrote. “If Arthur goes to the front in March I shall have to return to England; otherwise I should remain in France.

“I think, if you come over, that we can persuade Arthur to come back. The London offer was from Sir Sam and we must never forget it. I will talk the whole position over with Arthur and see what can be done.”

Arthur went back to the 58th in March 1917, and joined the assault on Vimy Ridge, where he was gassed. His mud-stained map of the battle, showing the creeping barrages that proved so successful, is in the Toronto Archives.

He fought with the 58th at Passchendaele later that year, where he retrieved wounded and brought them to safety under heavy fire. He was promoted to captain on Sept. 15, but two weeks later he was back in London for 10-days’ rest.

He “made the impression on me of a broken old man,” Anna wrote her daughter.

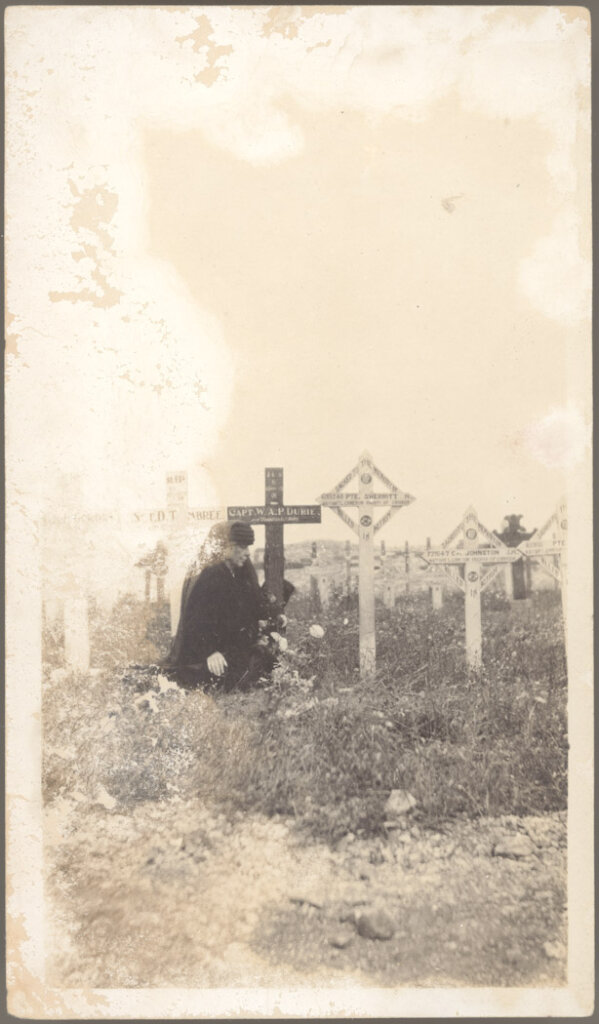

Anna Durie at her son Arthur’s grave near Lens, France, circa 1921. [Photo: City of Toronto Archives]

Rest helped, but the brass “realize that his health is hopelessly broken, and so does he, and it is making him wild,” said his mother.

Arthur returned to London for another 14-days’ leave in December. He rejoined his unit on the 22nd.

Six days later, on Dec. 28, 1917, the 58th was relieving the 116th (Ontario County) Battalion at the site of yet another great Canadian victory. Hill 70 was the first major action fought by the Canadian Corps under a Canadian commander, Lieutenant-General Arthur Currie.

The Aug. 15-25 battle had given the Allies a crucial strategic position overlooking the occupied mining city of Lens. Six Canadians earned Victoria Crosses at Hill 70.

Now the Canadians were holding the line in a particularly active sector.

Durie’s ‘A’ Company occupied the Nabob trench on the right; ‘D’ Company took up positions in Nestor trench on the left, while ‘C’ Company assumed support positions in Congress and Catapult trenches and ‘B’ stood in reserve with the battalion headquarters in Counter trench.

The takeover was uneventful. The battalion had not suffered a single casualty in the month of December. That was about to change.

Early the following day, with a cold wind blowing from the north, the Germans unleashed a mortar onslaught. The 25-centimetre minenwerfer was an extremely capable weapon and, on this day, the enemy used it to great effect.

“At 9:45 a.m. a heavy trench mortar bombardment took place on ‘A’ Coys frontage and CANTEEN Communication Trench (Square N.8.b.) and reached its greatest intensity at 10 a.m.,” wrote the battalion’s acting commander, Major Dougall Carmichael.

“There were several casualties, including Captain W.A.P. Durie, O.C. [officer commanding] ‘A’ Coy., who was killed,” along with two enlisted men and two others wounded.

To be continued next week, Oct. 1, 2025.

Advertisement