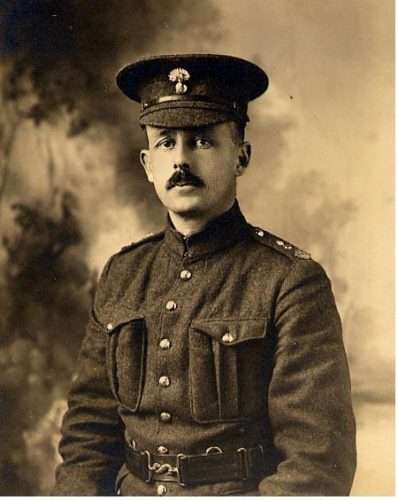

Private Harry Morris was wounded near Vimy, France, in January 1917. [Canadian Letters and Images Project]

Their work was cut out for them. They needed a new dugout “so we will have a place for the night,” Private Harry Morris wrote home in a letter to his family, published online by the Canadian Letters and Images Project (www.canadianletters.ca).

Despite the bombardment, they started a new dugout and repaired the damaged walls of their trench and a destroyed gun pit.

“[We] keep plugging along, very busy dodging shells.”

At 1:30 p.m., the First World War ended for 36-year-old Morris when a shell exploded nearby.

“I heard the explosion after I was hit. Shrapnel travels at a greater velocity than the sound.”

His thigh bone was shattered and his kneecap was split in two. His comrades dragged him to shelter, poured iodine into the wound, wrapped a tight bandage around his leg, and “no stretcher-bearers being near us,” laid him on a piece of galvanized iron and awkwardly carried him for two hours to a dressing station, where his leg was put in a cardboard splint.

“The doctor says, ‘Well…it means Canada for this boy.’ I cannot explain the feeling that came over me at that moment, to realize that I was going back to my beloved country and dear ones.”

He waited, growing colder and colder for five hours, for a horse ambulance. The officer commanded the driver to be very careful.

“‘Two dangerous cases inside,’ he shouts, ‘Look out for holes and drive slowly.’”

Morris is one of the cases; the other is a lieutenant with a head wound. The other patients were walking wounded. The ambulance got stuck in a shell hole and tilted over.

“Fritz is saying goodbye to me by dropping an occasional shell near the ambulance. The driver is doing his best to get us out, but it is too much for the horses. Every jerk goes through my leg like a knife.”

“‘Two dangerous cases inside,’ he shouts, ‘Look out for holes and drive slowly.’”

A team of mules, passing by carrying ammunition, is stopped and used to help pull the vehicle out to continue its rocky journey.

“In an hour and a half, we arrive at a crossroads, where we are transferred to motor ambulances, a relief for my leg after the rough cross-country trip. A short run of 15 or 20 minutes, we arrive at dressing station, where my leg is washed. I am inoculated against lockjaw and wooden splints put on the full length of my leg.”

The cardboard and wooden splints likely saved his life, for before splints came into regular use a few months later, 80 per cent of men with broken femurs died.

“I am nearly frozen and I can tell you all truthfully that I have never been so cold in my life before.” He was loaded into another motor ambulance, noticing words printed on the side—‘Presented by the Children of Nova Scotia, Canada.’ Civilians donated many of the ambulance vehicles used at the front.

Shortly after midnight, Jan. 18, he arrived at No. 23 Casualty Clearing Station (CCS).

“I am met by the doctor, who, after looking over my papers, which are tagged on me, asks me how I would like a nice warm bed and a hot drink. By this time, I am so cold that I could hardly talk, my teeth are chattering and making an awful noise. A piece of stick is placed between my teeth, my clothes are ripped off me. I am rolled up in a blanket, then hot water bottles are placed around me, lots of blankets over me, and a hot brandy makes me feel a little more comfortable. It was three or four days afterwards before I really was warm.”

To help him sleep, Morris was given a sleeping draught and sandbags were placed to brace the splints. He woke at 4 a.m., still shivering.

At 9:30 a.m., bone and foreign matter were removed from his leg.

“My wound was stitched up and, to tell you the truth, I now felt fine. My leg was swollen to twice its normal size, but it did not bother me much. I had far too quick a pulse and, as I learned afterwards, my blood pressure was very bad.

“I suffered a good deal of pain,” Morris wrote. Even so, “I shall never forget the kind manner in which I was treated by everyone, from the orderlies to the Colonel,” who informed him his wound was dangerous.

“At a CCS a patient is hardly ever kept longer than two days. My case being a dangerous one, I was kept until Friday, Feb. 9, when I left at 9 a.m. for Boulogne.”

“I suffered a good deal of pain,” Morris wrote.

His train arrived at 11 p.m. and was welcomed by a crowd and a waiting ambulance. “A French woman gave me a cigarette.”

Then it was off to the Canadian General Hospital, where he arrived at about 11.30 p.m.

“[My wound] was dressed first thing this morning. I am at last beginning to feel warm again.”

Morris’s medical records (online at Library and Archives Canada) show he was moved in February to 2nd Eastern General Hospital in Brighton, England, and after five weeks of further healing, to David Lewis Northern Hospital in Liverpool for rehabilitation.

On Sept. 14, “wound healed” was entered into his medical records and the next day he was aboard HMHS Araguaya, headed from Liverpool to Canada.

Advertisement