Auschwitz concentration camp. [Courtesy of Peter Waiser]

At least half the six million Jews who died in the Holocaust were Poles who met their end in Nazi death camps located in Poland. Another 1.9 million non-Jewish Poles, including political, religious and intellectual leaders, also died in Nazi camps. Numerous more were killed in massacres and executions.

In a country of 38 million people, Poland’s Jewish population today numbers just 5,000. Before the Second World War, it was 3.3 million.

A destroyed gas chamber at Auschwitz. [Courtesy of Peter Waiser]

At great personal risk, Grabowski has spent 20 years examining the Holocaust in Poland and the role Poles played in it. For the past five, he and his team of researchers have been investigating individual cases in nine Polish counties.

Tapping archives in Poland, Germany and Israel, as well as face-to-face interviews with survivors and others, they tracked the fate of tens of thousands of Jewish Poles from their homes to the camps where most of them died.

Grabowski’s 1,200-page report, to be released later this spring, is “very bleak.” And in what is bound to add fuel to the fire of Polish government denial and right-wing indignation, it paints a clear picture of widespread complicity in Jewish deaths.

“Less than one-fifth survived,” said the author, a history professor at the University of Ottawa. “We are dealing with tens of thousands of dead Jews who were either murdered by the Poles or were delivered to the Germans for execution.

“We are talking here about complicity in the Holocaust on a quite significant level.”

Grabowki’s findings came as Poland’s right-wing president, Andrzej Duda, signed a controversial bill making it illegal to accuse the nation of complicity in crimes committed by Nazi Germany, including the Holocaust.

The law, which will next be reviewed by the country’s Constitutional Tribunal, also bans the use of terms such as “Polish death camps” in reference to Auschwitz and other Nazi extermination sites. Violators can be punished by fine or a jail sentence of up to three years.

Grabowski, who has received death threats over his work, says the law will “paralyze independent research into the role of Poles in the Holocaust,” especially in a country where police and prosecutors have all but replaced an independent judiciary since Duda’s nationalist Law and Justice party was elected 30 months ago.

“This law is intended to muzzle, stifle and stop any kind of serious research into Polish complicity during the Holocaust,” said Grabowski.

History professor Jan Grabowski of the University of Ottawa. [Jan Grabowski]

Germany invaded in September 1939, overrunning the country in six weeks. Nazis disdained Poles. They killed and enslaved millions during a brutal occupation and, says Grabowski, “were never interested in drafting Poles to co-operate.”

Germans and Ukrainians operated the death camps. But the Nazis had other ways of exploiting Polish sentiment.

“The Germans gave licence to vile behaviour,” Grabowski, 55, said in an interview with Legion Magazine. “What you see, especially, is that violence toward the Jews grew with every month of occupation.

“People knew that hurting the Jews was not only not going to bring them any shame, it was actually going to bring them rewards, and they jumped on the German bandwagon. This is the part of the story Polish society does not want to hear today. Very many people got rich off Jewish misery and then off Jewish death. There are very many dark areas that have not been properly researched in Polish history until now.”

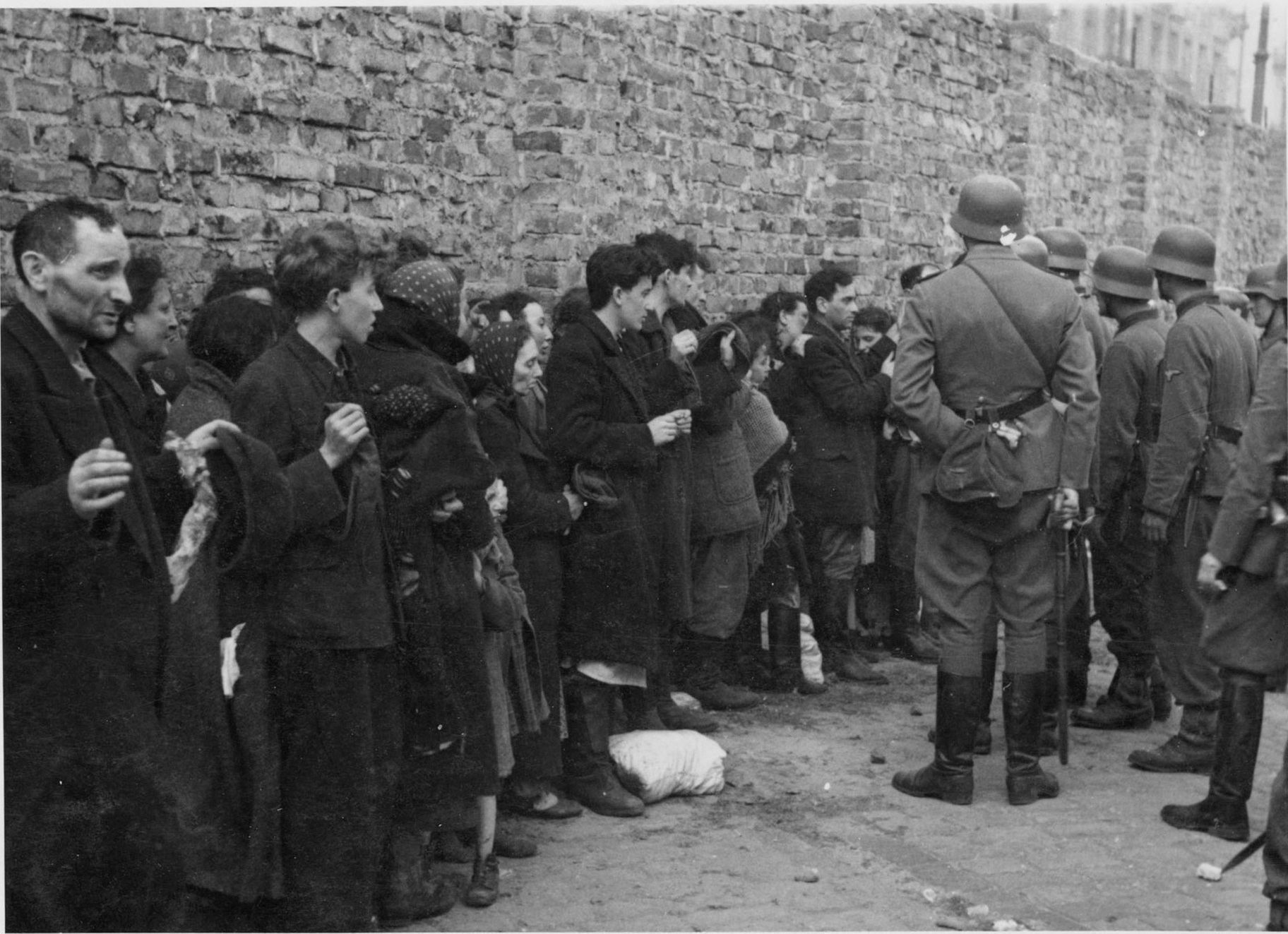

During the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in 1943, captured Jews are searched and interrogated before being sent to a concentration camp in Poland. [Wikimedia]

“Mass murder of Jews in Poland happened in their midst,” said Grabowski. “The camps were next door. It was a question of common knowledge, not of vague rumour like it was in France.”

Right-wing zealots regularly harass Grabowski. His family has been threatened. Polish groups have tried on multiple occasions to get him fired from his teaching position. The Polish League Against Defamation called his views damaging.

“He falsifies the history of Poland, proclaiming the thesis that Poles are complicit in the extermination of Jews,” the league wrote in letters circulated to universities in Europe and North America. One letter was signed by 130 Polish scholars—none of whom, Grabowski’s supporters said, has any role in Holocaust studies.

“Grabowski fails to adhere to the fundamental rules of researcher’s credibility,” his detractors said. “He uses vivid and exaggerated statements to create propagandistic constructions, rather than to provide an honest picture.”

Scores of pre-eminent international Holocaust scholars in turn wrote to the chancellor of the University of Ottawa, defending Grabowski as a scholar of “impeccable personal and professional integrity,” praising his courage and damning his critics.

“The current attack on Prof. Grabowski by the Polish League Against Defamation…is baseless, putting forth a distorted and whitewashed version of the history of Poland during the Holocaust era,” their letter states.

The university’s Human Rights Research and Education Centre issued a statement condemning the league and lauding the quality and depth of Grabowski’s work.

“The League has sought to highlight the efforts of Poles who courageously protected Jews—a small group of people who unquestionably deserves recognition, especially given the hostility and danger they encountered during and after World War II,” it said. “Nevertheless, the basic facts of the Holocaust in Poland are stark and inexcusable and merit ongoing awareness to help prevent their recurrence or similar events.”

More than 300 Polish guerrilla fighters, known as Cichociemni (the silent and unseen), were trained in Britain and parachuted into occupied Poland starting in 1941. The first such air drops behind German lines, they led the resistance movement against the Nazi occupation. The Armia Krajowa (the home army) peaked at 300,000 men and women, considered by far the biggest resistance movement under the Third Reich. It succeeded in briefly liberating Warsaw in the summer of 1944.

Poland’s exiled armed forces were constant contributors between 1939 and 1945. By May 1940, there were 84,500 Polish troops fighting in France and Syria.

Poles also fought in Italy, North Africa and on the Eastern Front. Nearly 150 Polish pilots flew in the Battle of Britain, and the Polish navy served in the Baltic Sea, the North Sea, at Dunkirk and Dieppe, during the Battle of the Atlantic, and at the D-Day landings. The 1st Polish Armored Division became part of the 1st Canadian Army and ultimately closed the Allied gap at Falaise, an escape route for German forces.

But at war’s end, Poland “emerged as the heaviest loser on the winning side,” historian Andrzej Suchcitz told the Ex-Combatants Association in Great Britain.

Shoes taken from prisoners at Auschwitz. [Courtesy of Peter Waiser]

“VE-Day did not sound the bells of victory and a time of peaceful reconstruction. It ushered in a new foreign occupation in which the new Poland, robbed of half her territory annexed by the U.S.S.R., found herself under the Soviet heel.

“The struggle continued for a further 45 years until true independence was once more restored in December 1990.”

Advertisement