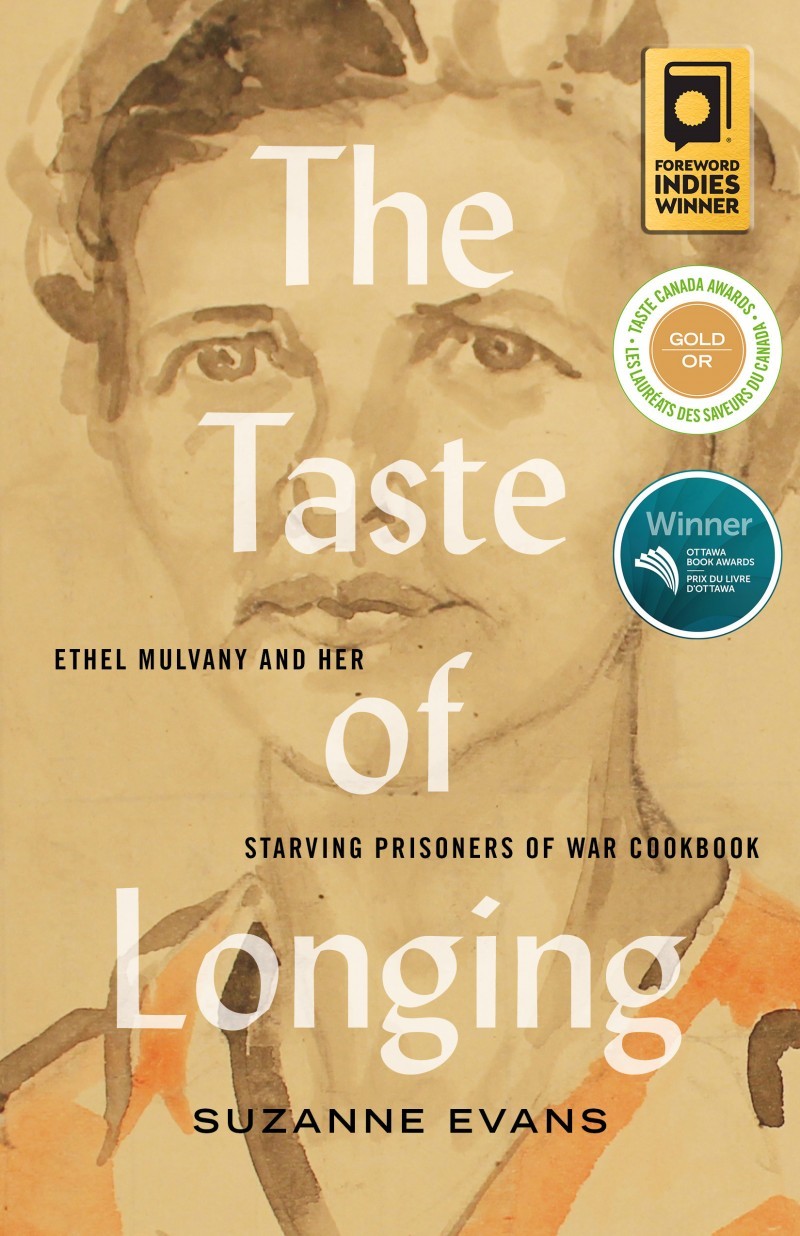

The award winning book, The Taste of Longing by Suzanne Evans, has been optioned by acclaimed documentary filmmaker Noura Kevorkian. [BTLBooks]

But having discovered the Second World War story of Canadian Ethel Mulvany, her understanding of hunger changed.

On Feb. 15, 1942, the Imperial Japanese Forces landed on Singapore island and forced the surrender of an Allied garrison of 90,000. In what Prime Minister Winston Churchill considered the “worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history,” thousands of captured civilians, including Mulvany, were among those to be rounded up, separated between men and women—the latter with children—and imprisoned at Changi Jail. The ensuing years would be ones of misery and longing.

It was there, amid such horrendous conditions, that the former Australian Red Cross ambulance driver resolved herself to boost morale: “Mulvany organized the collection of recipes among these starving women who gathered each afternoon to talk about food,” said Evans. “I suppose you could argue that it was, in a sense, a way to escape.”

Recorded in the blank margins of salvaged newspapers, both the recipes and Ethel Mulvany herself survived the war and returned to Canada. Her morale-nourishing tale has since been detailed in Evans’ 2020-published tome The Taste of Longing.

Here, Evans highlights Mulvany anew, complexities and all.

Ottawa writer and historian Suzanne Evans has written two novels, her first being Mothers of Heroes, Mothers of Martyrs. [Suzanne Evans]

I got a job as a research fellow at the Canadian War Museum to unearth stories of Canadian women at war. While I was looking for these stories on the internet one day, I came across the Changi quilts [a Mulvany initiative during her internment].

I initially thought I’d get an article out of this, but then I found the cookbook she had published with all of these recipes she’d collected while she was imprisoned. Someone at the museum helped me realize there was more to it than an article.

I was very, very lucky, as a little while after, I mentioned Mulvany to a neighbour across the street. It turned out my neighbour knew her nieces—who lived in town. One, who inherited Ethel’s wartime ephemera, lived 10 minutes’ drive from me. I went to visit her many times, and each time, it seemed as though more and more would bubble up from her basement archives. Slowly, surely, I got to know Ethel.

About Mulvany herself

She was born on Manitoulin Island, Ont., in the middle of Lake Huron. From there, she went to Toronto and Montreal—both times for university—but when the Great Depression hit and her father died, she couldn’t afford the schooling anymore. So, she took a job studying international educational systems. However, she got sick aboard a ship, so they got [British] Dr. Dennis Mulvany to come check in on her.

They were married a few months later. The couple lived in India from ’33 to ’39, and with some travel and interruptions, they both ended up in Singapore, where he was a British military doctor. So, that’s where they were when it was attacked in December ’41 through to the surrender.

Separated from her husband, Ethel was pretty desperate to communicate with him. The Japanese wouldn’t allow the women to write letters or visit. Phoning was just as much out of the question. She then came up with the idea of stitching messages. Mulvany managed to get a hold of sheeting material that could be cut into six-inch squares. These squares were passed onto women who could stitch something close to their hearts beside their names. Together, they were formed into signature quilts. Three quilts were made, one each for the Japanese, British and Australians. Those latter quilts were permitted to be sent to the Allied soldiers recovering in hospital. That way, the men got to know their [female] loved ones and children were alive.

Ethel’s gathering of recipes was probably concurrent.

Now, it should also be said that Ethel would likely not have been an easy person to be with—certainly not in a crowded jail. She could be controlling and overbearing. But she was also absolutely vibrant and just go, go, go all the time.

About Mulvany’s compiled recipes

I decided to include the recipes at the beginning of every chapter. I thought that if you could almost smell and taste what those women were dreaming of in hunger, you could have a different avenue of accessing their experiences through the war. I’ve even tried making a few of them myself. One, a crumb cake, I made for the filmmakers who’re adapting my book for a documentary, which went well. I’ve also made one that’s meant to treat rheumatism—I have to say, it was repulsive.

About becoming Mulvany’s biographer

I hope readers realize that there are different ways to suffer in war. War is not just on the battlefield. It happens in the kitchen—and also in the mind. Let me be clear that it requires incredible bravery to be a soldier on the battlefield. But it’s a different kind of bravery to endure the slow agony of not knowing what is happening in the outside world, of not being in control of your own fate, which was how those prisoners would have felt. So, yes, Mulvany exhibited a different kind of bravery, one that I remain proud of highlighting in The Taste of Longing.

This abridged interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Advertisement