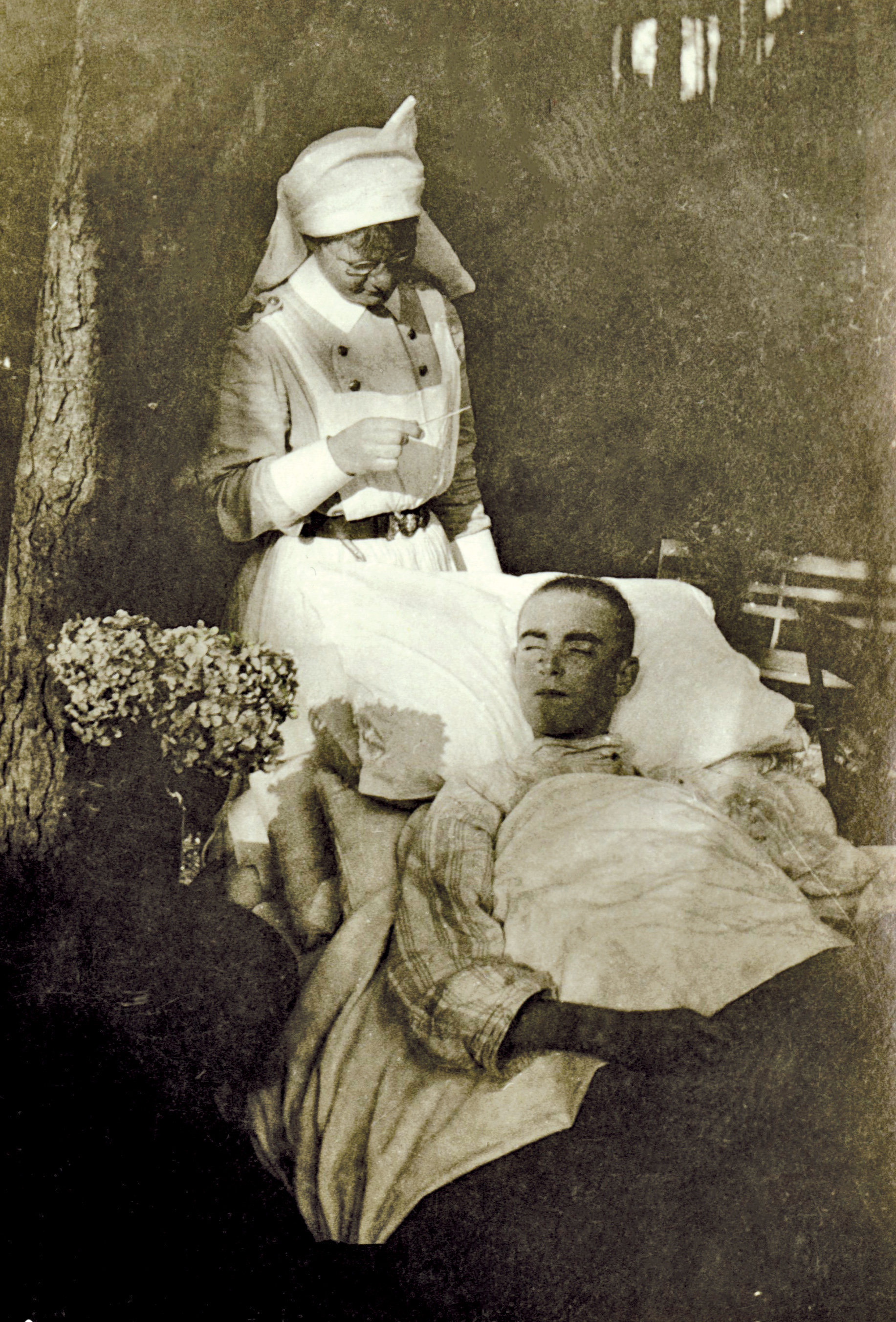

Nursing sister: Alfreda Attrill in her Canadian Army Medical Corps uniform, 1916. [Health Sciences Centre Winnipeg/999.18.8]

The author was a nurse in the First World War. She lived in Winnipeg and graduated from the Winnipeg General Hospital in 1909. She went overseas with the first contingent of the Canadian Army Medical Corps and served the entire war in France, Salonika and England. Her first posting was at the #2 Stationary Hospital, which was established in the Golf Hotel at Le Touquet, France, in 1914. This was written in March 1915. This letter is provided by her great niece, Sandra Moulton.

IN A WAR HOSPITAL. It may be of interest to you all if I try, however inadequately, to describe three days of our recent work here, as the best means of impressing a picture of the conditions on your minds.

This is by no means ‘the front’ and compared to those of the English sisters and the Red Cross volunteers, our experiences have been tame, but nevertheless, last week echoes of the fierce fighting around Le Basse and the dearly bought success of Neuve Chapelle has connected us with the battle at the front very quickly, and human wreckage has been cast up to our doors.

I am doing night duty at present. On March 8th, quite a number of new patients had been admitted. There is also a message (March 9th) from Boulogne, that a trainload of about 150 are being sent to us, of which 84 are bad stretcher cases. The night nurses hurry from room to room making themselves acquainted with patients they have not seen, doing PRN [pro re nata—as needed] dressings and carrying out whatever orders can be done ahead so as to be free later. The day staff dons rubber aprons and come on duty to assist in receiving the patients, ambulance beds ready, sheets on radiators, record books prepared, etc.

Attrill (second from left) and three other nursing sisters during the First World War. [DND/LAC/PA-006827]

It is close upon midnight when the 10 or 12 ambulances make their first journey from the Etaples Train Station three miles away through the woods, and the unloading and passing before the admitting officer begins. It is a ghostly procession to which we have become accustomed. Quietly, they file along the corridors—these broken men from the trenches whose deeds when they are properly known will make the world dumb with respect, whose accumulated miseries none can realize. Khaki caked with clay, ragged, dirty, worn out and silent, they stumble into the warmth of the wards. In the droop of the body, the dull retrospective eyes and restrained speech, one catches glimpses of the weeks of horror that followed Mons, the countless nights of slow agony.

A long line of stretchers fills the hallways but it is the exception to hear a groan or complaint, though this is the convoy with the worst wounds we have yet received. Bodies are literally shattered and the journey must have been a terrible one. At each station, we are told, some dead have been removed. Cases of gangrene have already developed and in 36 hours are very far advanced. These are the cases especially allotted to me. We also hear that every one of the 5,000 beds in Boulogne has its occupant and that 1,000 wounded have been passed on to Rouen and Havre.

“How many hours before you were picked up?” I ask one soldier.

“Twenty-six, Sister, but I dug my head into a refuge, for it was raining lead like hail and I was hit only once again, thank God.”

“When were you found?”

“After laying all day. I was hit shortly after relieving in the trench, yesterday morning. Shall I get better?”

The doctor says it is gangrene.

About 3 a.m. one has time to walk from bed to bed and inspect the 45 or so new patients. Here is a child of 17 (officially 20) moaning softly, with a shattered arm, blue eyes and pink cheeks, looking almost infantile. There is an old soldier swathed in bandages, a cigarette alight, declaring cheerfully, “It’s a bit sore but it will be right soon sure.” Further on, a round faced, dark curly-haired boy of 22 with a shattered arm, and a painful right stump (a badly shattered and gangrenous leg having been amputated) lies in restless slumber experiencing in dreams the horrors over again.

There is one from our own Canada; a homestead near a Saskatchewan town is his home. Many hours he lay on the field, numerous wounds of the thigh, now suffering of malignant edema (gas gangrene). The surgeon nods. The sisters prepare for an immediate operation. We know not what morning will bring.

As a rule, these sufferers are silent, but here and there writhing forms and smothered groans tell of agony we [are] helpless to relieve. Some have limbs reduced to pulp, others have lost an eye, and a few unconscious cases claim close attention. Lifting a sheet perhaps one discovers a hemorrhage or a gaping cavity where shrapnel has torn away a joint.

As one passes along, a voice says, “It’s awful quiet here, Sister, but I seem to hear the guns yet. There were 500 of them speaking at once on Tuesday morning and it was hell.” Now and then, a sudden cry and convulsive awakening indicate the exhausted nerves of a dreamer. He thought he was advancing through mud and thorn bushes towards the enemy trench, wrestling with some man who may kill him. He awakens panting and perspiring and sitting up staring.

Alfreda Attrill tends a patient. [Health Sciences Centre Winnipeg/2010.7.112;]

When the new arrivals are finally settled a list of 25 names is sent up to the ward of those to be transferred to another hospital farther south. This is owing to the policy of constant evacuation to keep vacant beds close to the front. This necessitates re-dressing those wounds, which may not receive attention for the next 12 hours. Practically every article of clothing has to be pulled on the helpless patients. Sometimes there are more than 20 dressings to be done and only an hour to do them. The transfer of patients is even worse than admitting them.

We are always glad to send men to England, particularly when their wounds require the long furlough they so thoroughly deserve—willing, as they are, to go back to the frightfulness of the trenches if their king needs them. The prospect of even a week in Blighty will bring a smile to the most pain-drawn face.

In one room is a young fellow who enlisted as a private in the army, mis-named Ritchimis. Quiet and reserved, he studies Henry V’s address to his soldiers while his wounded hand is being treated. Agincourt is only a few miles away from us. There was never a time when people sacrificed more for their country.

Advertisement