It was 1942 and one evening 20-year-old Winnifred Davidson, known as Davey to her friends, was whisked away from Toronto in an unmarked maroon car and driven to an undisclosed location. When she arrived there, she was instructed, “Don’t tell anyone where you are or what you’re doing here.”

That’s how Davidson began her career at a top-secret training school for spies known by many names but commonly called Camp X. She was part of the first contingent of women allowed into that men’s training facility.

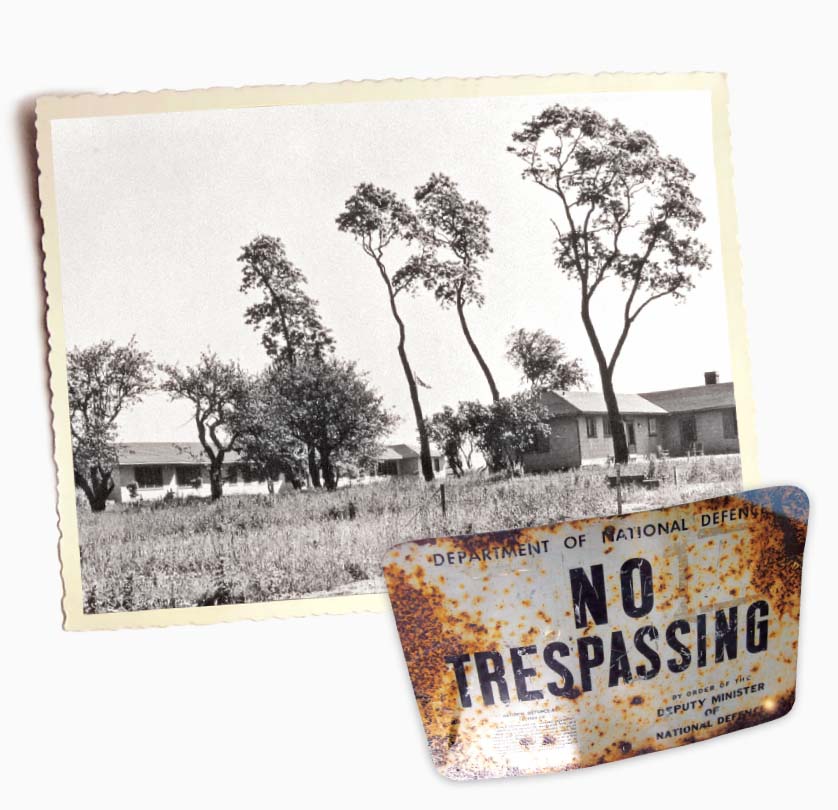

According to Davidson, the camp, located on a wooded 110-hectare site on the northwestern shores of Lake Ontario near Whitby, Ont., “looked much like any army base, but nicer and quieter. There were a number of barracks where we slept, a one-storey office building where we worked that included a canteen, and not much else.”

What was different was that there were no stores, telephones or cars at Camp X, the area was enclosed by a fence, and all mail sent to staff went first to an address in Toronto. Also out of the ordinary were the subjects taught to the secret agents training there, such as how to interrogate prisoners, safe blowing, information gathering and how to kill with the thrust of a knife.

Davidson worked in the communications section as a keyboard operator. “After arriving at Camp X, we had one week to learn Morse code and Murray code [which used punched tape ribbons to transmit messages] before pitching in to translate incoming and outgoing calls to and from Britain,” Davidson said. “We used a Kleinschmidt teletype machine and messages came in via high-speed Morse code and went out on punch tape. The office ran 24/7. We worked eight-hour shifts.”

Winnifred “Davey” Davidson and her brother Harold, both served during the Second World War; Davidson’s medals; tape with Murray code punch marks. [Courtesy of Winnifred Gardner; Wikimedia; Whitby Archives/D2013_008_001]

Camp X was born after British Prime Minister Winston Churchill instructed British Security Co-ordination (BSC) chief, Winnipeg-born, First World War fighter pilot William Stephenson, to create “the clenched fist that would provide the knockout blow” to the Axis powers. To the British, Camp X was known as STS (Special Training School) 103; the Canadian military called it Project J; to the RCMP it was S25-1-1.

The camp was run by Britain’s Strategic Operations Executive (SOE). One of its roles was to train Americans in intelligence gathering, but couldn’t do so on American soil because the United States had not entered the war. Camp X solved the problem. It opened on Dec. 6, 1941, one day before Pearl Harbor was bombed, forcing the U.S. into the war. Designed as a top-secret training school, it was the first official site for British, Canadian and American intelligence officers during the Second World War, and the first such purpose-built facility in North America.

The location “was chosen with a great deal of thought,” according to historian Lynn Philip Hodgson’s website, Inside Camp-X. “[It was] a remote site on the shores of Lake Ontario, yet only 30 miles straight across the lake from the United States. It was ideal for bouncing radio signals from Europe, South America and, of course, between London and the BSC Headquarters in New York. The choice of site also placed the camp only five miles from DIL (Defence Industries Limited), currently the town of Ajax.”

The website also reveals that, during the war, scientists and seamstresses operated secretly from the basement of Toronto’s Casa Loma museum for an arm of Stephenson’s organization called Station M (for magic), manufacturing items secret agents needed once behind enemy lines (Artifacts, March/April 2016). They created compasses concealed in combs and silk scarves printed with detailed maps of the country where the agents’ missions took them. Also designed there were clothes made with cloth and buttons from those countries, forged visas, passports and currency created on typewriters smuggled out of countries where agents would land.

Davidson’s work was part of an important telecommunications network between Britain and Canada known by the code name Hydra. Raw data came in via Hydra and flowed through to the communications building where Davidson worked. There it was printed in code.

Davidson worked with about nine other Canadian Women’s Army Corps (CWAC) members, but noted that most of the staff were civilians. “That meant,” she said, “no army discipline. We didn’t need to be concerned about things like having our room inspected or attending church every Sunday. Such rules couldn’t be enforced on civilian workers–or on us.

“I loved my experience at the camp,” she said. “But my situation was different than others there. My brothers, sister and I were raised in Toronto by our single mother. When I was 15 and almost finished Grade 11, our mother died suddenly. After that I quit school, the family split up and I had to find ways of earning a living and looking after myself.”

Davidson worked briefly as a mother’s helper then taught roller skating before joining the CWACs when she turned 18. That gave her a job plus a place to eat and sleep. By then her sister, Marion, and brother, Harold, were contributing to the war effort too: one as a “bomb girl,” working in a munitions factory, the other serving with Canadian troops in Europe.

Camp X was a communications hub between London and the British Security Co-ordination office in New York. [Whitby Archives]

“There wasn’t much to do socially at Camp X,” Davidson recalled. “But we were usually too tired after the day’s work anyway.” One activity they did enjoy was pool. Across the road from her office was the headquarters, the commanding officer’s house and a pool table that, at first, only the men could use. But women eventually were allowed to play, too.

They could also attend the movie theatre in Oshawa on weekends, but were driven there and picked up right after the show ended and taken back to the camp.

Charles “Chuck” Gardner served in the Canadian Armoured Corps during the Second World War. After returning from England, he was posted to Camp X, becoming sergeant responsible for communications. He and Davey were married in September 1945, just as the war ended. A month later, Davey was discharged, although her husband’s job there didn’t end. So, while he continued to live at Camp X, she lived with her mother-in-law briefly before getting permission to rejoin her husband at Camp X. A year later, their son, Don, became the first baby born at the spy camp. Their daughter, Janet, was born there a few years later.

The camp was secret but it had its own badge. [Lynn Philip Hodgson]

After the war, the camp remained in operation as Hydra continued to be an essential communications link between London, Washington and Ottawa.

“Camp X remained open after the war ended,” said Davidson, “[In part] because Igor Gouzenko, a cypher clerk at the Russian Embassy in Ottawa, had defected to Canada after disclosing the Soviet’s espionage operation and a secure place was needed for him and his family.” The Gouzenko family and RCMP escort arrived at Camp X in September 1945 and remained there until arrangements were made for them to live safely under a new identity in Mississauga, Ont.

In 1947, the Canadian government assumed responsibility for Camp X, operating it as a military signals station until 1969. At that point, some buildings were demolished and others moved.

Today, Camp X is remembered by a public park on Boundary Road in Whitby, Ont., where the camp once stood. It’s called Intrepid Park, after Stephenson’s telegraph address which was, incorrectly, believed to have been his code name. A monument erected there in 1984 is surrounded by the flags of Canada, Britain, the U.S. and Bermuda, where Stephenson died. There is also a Camp X mural on the Public Utilities Commission building at the north end of the park and a former barracks is located at the Humane Society of Durham Region in Whitby.

Camp X artifacts are scattered. For more than 30 years, history buff Robert Stuart had a large private war memorabilia collection at the Ontario Regimental Museum. It included Camp X artifacts, such as a camera that shoots bullets, a sword disguised as a cane and a lipstick tube concealing a dagger. But after Stuart’s death, his daughter inherited the items and put them up for sale. In 2010, the Canadian War Museum acquired 15 items with verifiable histories from the collection, including commando overalls, a British suitcase radio and a half-metre length of railway track used for demolition training.

In 2012, a permanent exhibition opened at the Durham Regional Headquarters in Whitby. There you can see maps, forged currency and signs. Another collection of items, entitled The Station M Collection, are at Casa Loma, although some were stolen in 2014. Other artifacts can be seen in the Richard Brisson Collection at the Military Communications and Electronic Museum in Kingston, Ont.

The buildings at Camp X had restricted access by order of the Department of National Defence. [Whitby Archives/29-005-001; Robert T. Bell/Flickr]

The British Archives in London has a manual from the camp entitled How to be a secret spy. It was written by notorious British double agent Kim Philby and film critic and author of spy films, Paul Dehn.

During the Second World War and decades after, those connected with Camp X were sworn to secrecy. Now that the stories of the camp can be told, Canadians finally can discover the important role Camp X played in Canada’s history. Those who were part of that facility are being recognized, too. The Canadian Senate acknowledged the contributions of Davidson and Gardner in 2005, the International Year of the Veteran, which coincided with their 60th wedding anniversary. Davidson has many thank-you letters, a medal recognizing her years of service and a Canadian Volunteer Service Medal. Although Gardner died in 2007, Davidson only recently left the Leitrim, Ont., home they moved to after Camp X closed.

Passing through Camp X

It is believed approximately 500 people trained at Camp X. Many notable figures were known to have been there in various capacities, including:

Ian Fleming, the author of 12 James Bond novels based on his own knowledge of the intelligence community.

Paul Dehn, a British film critic who also wrote screenplays including Goldfinger, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold and Planet of the Apes. He won an academy award in 1951 for the original story for Seven Days to Noon.

Roald Dahl, the award-winning British author, wrote numerous children’s books, including James and the Giant Peach and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, plus adult books.

David Ogilvy, the founder of the Ogilvy and Mather Advertising Company who wrote three books on the basic principles of advertising.

Stirling Hayden, the American film actor who ran a network during the war assisting American and Allied aircrew escape occupied Yugoslavia.

Kim Philby, the British SOE operative who would later be revealed as a double agent for the Soviet Union.

Advertisement