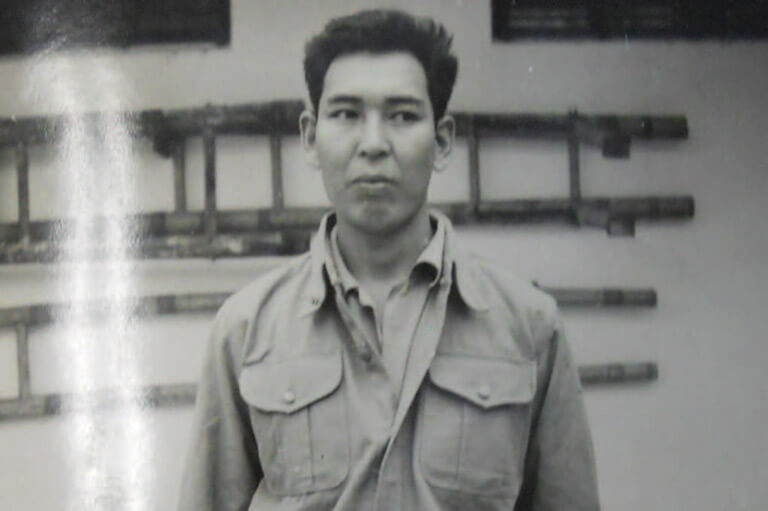

Kanao Inouye, known as the Kamloops Kid, is pictured while in custody in 1945. [Wikimedia]

It was on or around Sept. 10, 1945, when the former Canadian prisoners of Ohashi prisoner-of-war camp in Japan laid eyes on their salvation.

The men, having been imprisoned since the fall of Hong Kong almost four years earlier, expected an American liberation. This they would receive but, for now, their visitors turned out to be a single Canadian army captain and a corporal.

The pair’s arrival confirmed that the war was indeed over. That unto itself was hardly a surprise, however, as Ohashi had been one of the first camps to learn of the Japanese capitulation on Aug. 15, 1945.

Moreover, since VJ-Day, the prisoners had been so inundated with food parcels from U.S. air drops that they had created a giant sign reading “No more.”

It was nevertheless heartening to see their countrymen. Despite little news surrounding their return home, cheers filled the air at a very different announcement: Kanao Inouye, a prison guard known for inflicting terror and torture, had been captured and was awaiting trial for his actions.

Kanao Inouye, a prison guard known for inflicting terror and torture, had been captured and was awaiting trial for his actions.

The significance of Inouye’s impending justice went beyond the disdain so many Allied prisoners had developed toward their captors. Inouye, after all, had not been raised beneath Japan’s rising sun, but in Kamloops, B.C.

Born to immigrant parents on May 24, 1916, the Japanese Canadian laid claim to a difficult childhood.

His father, Tadashi, had earned the Military Medal while serving with Canadian forces during the First World War. But back in Kamloops, the young Kanao was said to have endured racist abuse.

Those memories stayed with him. By the mid-1930s, after graduating high school, he decided to leave Canada. Inouye travelled to Japan for further education. There, he attended Waseda University in Tokyo and, in 1940, transferred to an agricultural college.

In December 1941, Inouye would have learned of the Japanese assault on Hong Kong. The British colony, in part defended by The Royal Rifles of Canada and The Winnipeg Grenadiers, fell on Christmas Day.

His fate, it seemed, had been sealed. Under Japanese law, a son of a Japanese father was, by extension of that nationality, himself a Japanese citizen; therefore, in 1942 Inouye was called upon to serve Emperor Hirohito.

Group of Royal Rifles of Canada confined at the Sham Shui Po prisoner-of-war camp following the fall of Hong Kong in 1941. [LAC/PA-166579]

Inouye’s fluency in English was promptly recognized as a critical asset to the Imperial Japanese Army. A short time later, the B.C. native was sent to Hong Kong’s Sham Shui Po prisoner-of-war camp as an interpreter.

It was here that Canadian prisoners first met Inouye, who, at least according to those subjected to his ire, allowed years of resentment to bubble to the surface. In the eyes of these individuals, the guard and translator had been afforded a position of power—and the means for revenge.

Though Inouye’s precise motives have since become the topic of considerable debate, accounts from Sham Shui Po showcase a clear capacity for violence. In one instance, he beat a malnourished Canadian for not picking up a wooden plank. When that same bloodied and bruised prisoner expressed defiance, he received a rifle butt to the shoulder that broke his collarbone.

In another instance, Inouye caught a Winnipeg Grenadier trading food with a sentry. The PoW was subsequently made to stand for two days and nights holding a bucket of water in front of him at arm’s length. Any time the Canadian faltered, the guards—Inouye included—whipped him with their belts.

Fellow grenadier Art Ballingall became a victim when he failed to salute a visiting Japanese general. Despite his hands being full when the perceived infraction occurred, Inouye smacked him around the face with the blunt side of a sword. Ballingall spent about two months in the hospital with broken teeth.

The torture continued with grenadier Jim Murray, who was tied to a pole with his mouth taped shut and burning cigarettes placed in his nose.

John Norris, an officer, almost lost an eye when Inouye beat him senseless.

The memory of Inouye’s forbidding presence, however, was etched into the psyche of survivors.

While at Sham Shui Po, the Japanese-Canadian interpreter also participated in mind games. Unencumbered by an accent while speaking English to prisoners, Inouye could sneak up behind PoW groups, criticize the Japanese, wait for anyone to agree, then reveal the deception before punishing the culprits.

Dubbed the Kamloops Kid for his geographical origins and Slap Happy for his acts, Inouye’s tormenting of prisoners ended when he eventually left Hong Kong. The memory of his forbidding presence, however, was etched into the psyche of survivors, including those later sent to Japan as slave labourers.

It was the accounts of those survivors that would serve as the impetus for his lengthy trials, first for war crimes, then for treason.

Complications soon surfaced around whether Inouye should be charged with treason as a Canadian citizen or face a British war crimes court as a Japanese soldier. Initially, Prime Minister McKenzie King’s cabinet sided with the latter, although the controversy marred the ensuing proceedings.

Ultimately, recognizing his British subject status—as a Canadian still part of the British Empire—Inouye received a second trial overseen by a civil court. There, under the Treason Act of 1351, which extended to Canada through the British North American Act, he was sentenced to death by hanging.

In late August 1947, Inouye ascended the gallows at Stanley Prison in Hong Kong. His final words—or word—was reportedly “banzai,” the Japanese battle cry and a blessing to the country’s emperor, before the trap door dropped and the rope went taut.

So fell the Kamloops Kid.

Advertisement