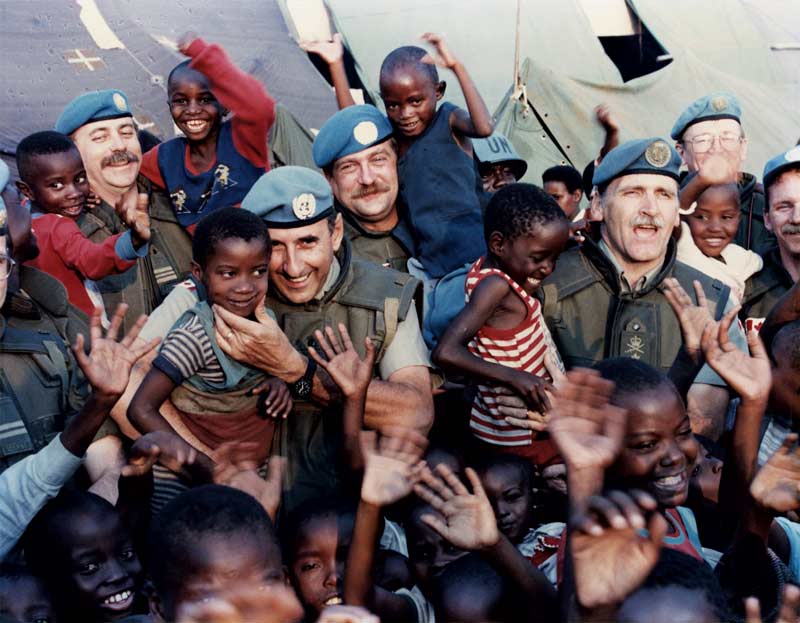

Members of the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda—including its commander, major-general Roméo Dallaire—pose with local children in 1994.[Corinne Dufka/courtesy Roméo Dallaire]

My youngest memories are of playing with toy soldiers. I was always drawn to the honour and chivalry of the warrior ethic. So, I joined the Canadian Armed Forces as my father had. My training for classic war was eventually adapted to apply to new peacekeeping

missions, but the pride of the uniform—green or blue—remained the same.

Of course, facing young boys and girls who had been abducted and forced to fight, or had been subjected to horrific sexual violence, was not what I expected to face when I took command of the UN Assistance Mission for Rwanda in 1993.

The noble warrior ethic to protect, to assess a situation strategically and act with clarity, was challenged when faced with a child recruited and used in war. I could not comprehend the world turning its back on the slaughter of 800,000 human lives in only 100 days.

The need for UN peacekeeping to be innovative, effective and accountable is as critical today as it was 75 years ago.

Peacekeeping is an imperfect tool that can never meet all needs or expectations. There are times when UN peacekeeping missions are prevented from, or fail to carry out, their mandates, thus putting into question the effectiveness or relevance of the system.

Canadian peacekeepers on patrol with the United Nations Emergency Force in Egypt in 1962.[Courtesy DND]

But, the alternative is unthinkable. The need for UN peacekeeping to be innovative, effective and accountable is as critical today as it was 75 years ago when the concept was first introduced.

According to the Institute for Economics and Peace, the overwhelming majority of the 20 least-peaceful countries face at least one catastrophic ecological threat. And most of the countries with the highest ecological threat rating currently suffer from conflict deaths and have moderate to high ratings for intensity of internal conflict. Therefore, countries must not abandon their efforts to work together to pursue global peace and security.

Bold initiatives are currently in place to improve the UN’s capacity to advance political solutions and support sustainable peace, improve the protection of civilians, as well as the safety of peacekeepers. So, we must not lose hope that change is possible.

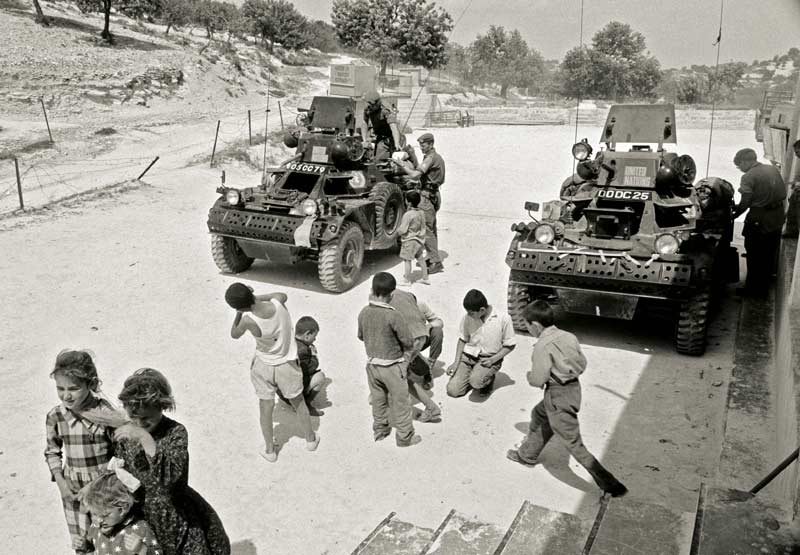

Canadian soldiers with the UN Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus patrol a street in Kyrenia in 1964.[UN Photo/BZ/UN7768313]

Children play around the force’s armoured vehicles in Nicosia.[UN Photo/BZ/UN7678303]

Canada had a critical role in the establishment of UN peacekeeping, and more than 125,000 Canadians have served in UN peace operations. Not surprisingly, Canadians consider peacekeeping part of the country’s identity. While there has been a steady decline of the country’s personnel contributions to such missions, Canada has supported those initiatives with expertise, policy guidance and innovation.

Part of this collaboration comes from the work of the Dallaire Institute,

through its efforts to build and strengthen the capacity of peacekeepers to prepare for missions where the recruitment and use of young girls and boys, whether in fighting or support roles, is likely to occur.

Canada also hosted the 2017 UN Peacekeeping Defence Ministerial in Vancouver, where the country contributed to the evolution of UN peacekeeping through two major initiatives: the Elsie Initiative to increase women’s participation in UN peace operations; and the Vancouver Principles on Peacekeeping and the Prevention of the Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers. The Dallaire Institute helped draft the latter, and to date, 105 nations have endorsed it.

Canadian peacekeepers visit an orphanage in Cambodia in the early 1990s.[Courtesy DND]

Dallaire visits a child-friendly civilian protection site in Juba, South Sudan, in 2015.[UN Photo/JC McIlwaine/UN7217578]

The most recent UN Secretary-General Annual Report on Children and Armed Conflict lists seven states and 48 non-state groups that committed grave violations against children in armed conflict in 2021.

The Vancouver Principles aim to empower UN member states to undertake early, effective and co-ordinated action to prevent the recruitment and use of minors as soldiers. This issue remains critical for the children involved, the peacekeepers who must face them and the global community that wishes to stop cycles of violence and generational conflict.

By endorsing the plan, UN members acknowledge the unique and far-reaching challenges with regard to child soldiers, and commit to prioritizing the prevention of this human rights violation. Doing so will help ensure that all peacekeepers—military, police and civilian—know how to interact with such children so everyone is kept out of harm’s way.

This anniversary of peacekeeping is an opportunity to rethink the approaches to peace and security.

As I know first-hand, the moral injuries resulting from exposure to grave atrocities can be catastrophic. The Dallaire Institute was created with the unique premise that preventing violence against children requires a dual lens: focused on prioritizing protection of children, as well as understanding the significant operational impacts on those in front-line roles.

This anniversary of peacekeeping is an opportunity to rethink the approaches to peace and security, the related priorities and how people can break cycles of violence globally. Canada’s contributions to address the challenges of empowering women’s meaningful engagement in UN peace operations, as well as prioritizing children are producing tangible, proactive changes to international missions.

The Vancouver Principles are motivated by the conviction that preventing the recruitment and use of children as soldiers is not a peripheral issue to peacekeeping, but rather, is critical to achieving overall mission success and to setting the conditions for lasting peace and security.

Sudanese women wait to register for a referendum in South Sudan in late 2010.[UN Photo/Tim McKulka/UN7391567]

Canada was among several countries on the UN mission supporting the initiative. Canadian soldiers pass supplies to children in Port-au-Prince in 2013, during the UN Stabilization Mission in Haiti. [DND/Combat Camera]

We recognize that by focusing on the protection of minors, pushing their well-being higher up on the international peace and security agenda, and making them a priority, the international community can begin to address the fragile situations that threaten the world’s most vulnerable.

The road is long, however, and the UN, civil society and academia must continue to provide new approaches to preventing conflict. Peace is possible, conflict is preventable and children deserve to be at the heart of our motivations.

A retired lieutenant-general and former senator, The Honourable Roméo Dallaire is founder of the Dallaire Institute for Children, Peace and Security. Shelly Whitman is the institute’s executive director.

Advertisement