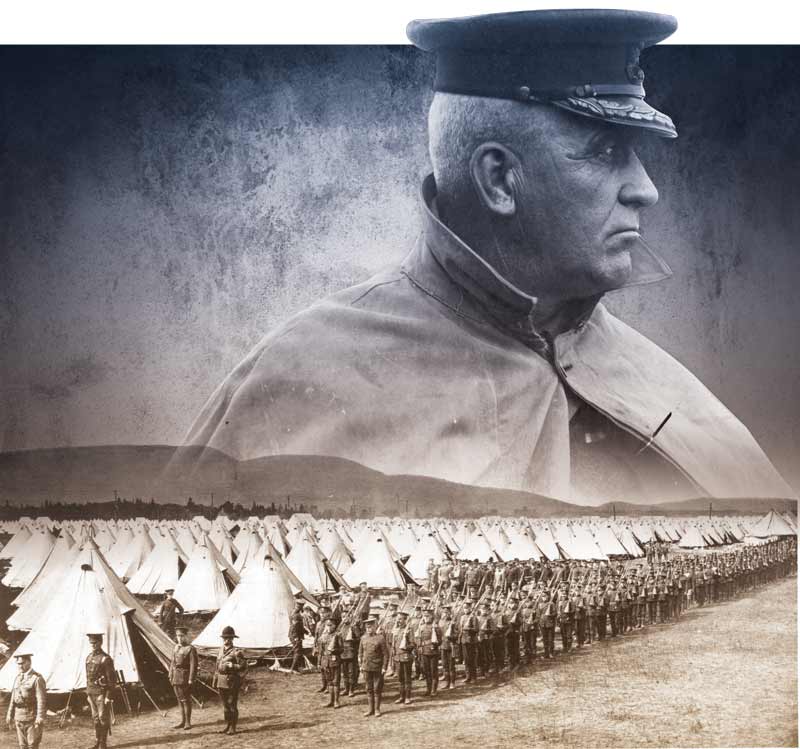

Minister of Defence and Militia Sam Hughes (opposite top) spearheaded the creation of the First World War training camp at Valcartier, Que. [J.A. Miller/University of Victoria Libraries/Wikimedia;DND/LAC/C-036116]

When the British Empire joined the war against Germany on Aug. 4, 1914, Canada’s indefatigable, rule-bending 61-year-old Minister of Milita and Defence, Colonel Sam Hughes, immediately discarded existing mobil-ization plans in favour of a general call to arms. He ordered all 226 militia units across the country to enlist men for the Canadian Expeditionary Force and ship them to Valcartier, about 25 kilometres northwest of Quebec City.

The problem was, there was nothing there. Everything had to be built from scratch, but Hughes was convinced that it could be done. It proved chaotic, controversial and magnificent.

Luckily in 1913, the government had purchased 1,777 hectares of sandy farmland on the east side of the Jacques-Cartier River nestled among forested hills as an eventual training camp for Quebec-based units. Hughes seized upon the site due to its proximity to a port.

Beginning Aug. 8, lumberjacks felled trees and prepared the land, while 400 workers built roads, cookhouses, medical and firefighting stations and numerous temporary buildings. They installed eight kilometres of water pipes, a large sanitary system and water pumps to provide 5.7 million litres of chlorinated water a day.

Telephone, telegraph and postal services were established. A massive camp space for at least 7,000 tents was laid out for the men to live in while they trained. Perhaps most impressive was the world’s largest rifle range—four kilometres long with 1,500 board targets.

The camp was wired for electricity and a five-kilometre railway spur was built to the village of Saint-Gabriel-de-Valcartier to connect to Quebec City. Everything was improvised and unprecedented, but Hughes’ faith in the country’s patriotic response was rewarded.

[Canadian Centre for the Great War]

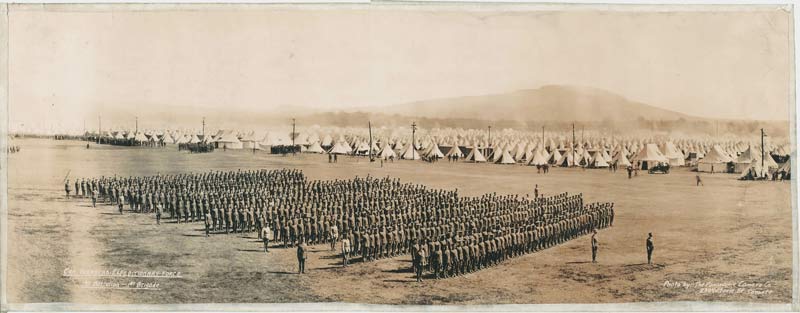

On Aug. 18, the first volunteers arrived by train. Three days later there were 4,200. Many of the men arrived without uniforms or equipment and everything from rifles and ammunition to cutlery and saddlery was shipped to the camp. The men were medically examined, attested and outfitted as soon as supplies arrived. Valcartier Camp became one of Canada’s largest cities, eventually accommodating a peak of 32,665 men. At least 6,767 horses, intended for transport purposes, the cavalry and the artillery, were held in poorly prepared corrals and, twice, horses escaped and stampeded through the facility.

Military drill and physical fitness commenced immediately, and the mass of men was organized into sixteen 1,000-man battalions. There were also cavalry, artillery, engineer, ordnance, medical, supply and other units needed to flesh out an infantry division and supporting arms.

Valcartier proved chaotic, controversial and magnificent.

“There was no loafing at Valcartier;” wrote visitor Elisabeth Flagler MacKeen, “it seethed and hummed like a hive.”

The challenges were worsened by the disruptive and overbearing Hughes, who meddled in everything and believed himself better than the 80 professional army trainers working non-stop. He even personally demonstrated bayonet fighting to the amazed soldiers.

“It seemed that his personality and his despotic rule hung like a dark shadow over camp,” wrote Frederick Scott, the senior army chaplain present.

Hughes’ refusal to allow alcohol in the camp didn’t help his popularity among the men.

Still, newspaper magnate John Bayne Maclean, no friend of Hughes, wrote that “any man who had done what he had in…organizing the…Contingent should have his sins forgiven.”

On Sept. 20, a final review and parade of the fit, smartly uniformed men took place in the presence of the governor general and the prime minister. About 9,500 civilian visitors, some family members of the troops, proudly witnessed the grand event.

In the last days of September, the men, horses and mountains of supplies were transported to Quebec City for embarkation. Thirty-one ships gathered at Gaspé and, on Oct. 3, the men of the first contingent, the Valcartier originals, left for overseas. And their fates.

Just weeks after the war began, the Canadian Expeditionary Force’s 1st Battalion 1st Brigade was on parade at Valcartier. [CWM/19740416-003 ]

Advertisement