Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson unveils the winning design for Canada’s new flag in December 1964.[Duncan Cameron/LAC/PA-136153]

Behold Canada’s flag, its bold simplicity. The flag the country waved at the Summit Series in 1972, that it waves at the Olympics, that flies above thousands of Canadian cottages. Flags are a symbol that unite a nation, but choosing the present version 60 years ago caused an uproar.

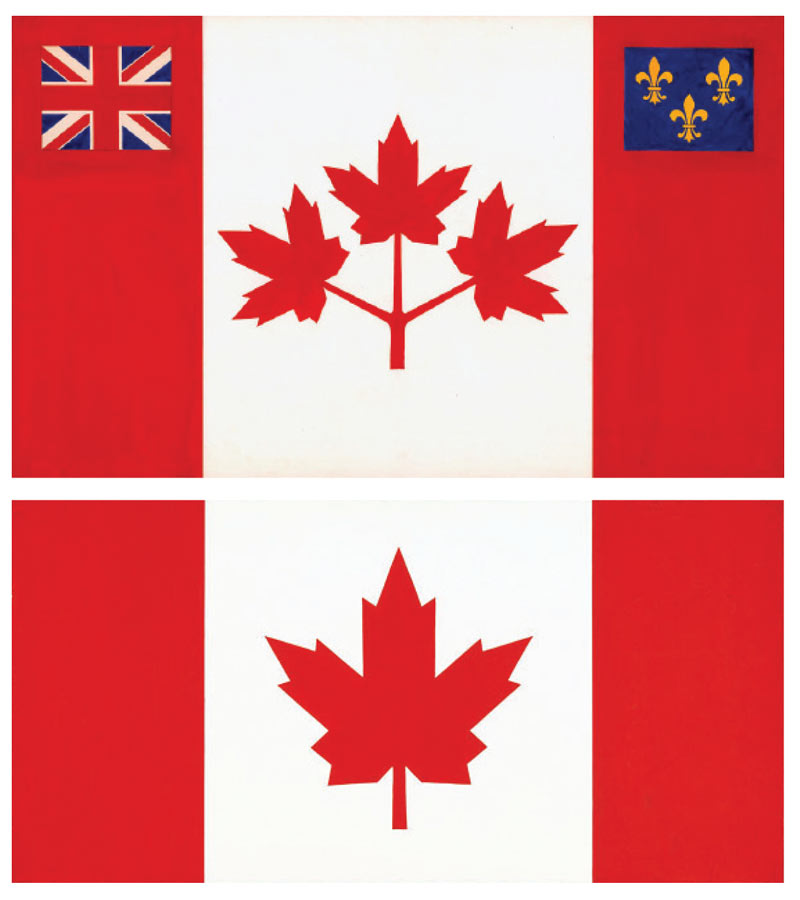

At the time, Canada used either Britain’s Union Jack, or occasionally, the Red Ensign, a modified version of the flag of the British Merchant Navy.

The idea of Canada having its own flag was first floated in 1925, by Prime Minister Mackenzie King, but the pushback was so great he abandoned the idea. He tried again in 1945,

without success. The country wasn’t yet ready to shrug off its colonial emblem.

In 1963, weeks after he was elected prime minister, Lester Pearson took a third shot at the idea. The country was almost a century old and was still using a flag borrowed from another nation. Surely, Pearson argued, Canada should have its own. His preference was for three maple leaves. John Diefenbaker, Pearson’s predecessor as PM and then the leader of the opposition, insisted that the Union Jack be part of the new version, to acknowledge the country’s British heritage. The design discussion was opened to the public and almost 6,000 alternate concepts—maple leaves, beavers, stars and echoes of the Union Jack among them—were ultimately considered.

Meanwhile, there were also Canadians who felt the country didn’t need a new flag, and that the issue was dividing a country that was already divided by language and geography. There was apathy, too; Quebec had little interest in the flag debate. “Quebec does not give a tinker’s damn about the new flag,” said MP Pierre Trudeau.

Pearson’s hope for three maple leaves eventually gave way to the current single red maple leaf with its eleven points, flanked by two solid red bars, a design proposed by historian George Stanley. Diefenbaker complained that it looked like the Peruvian flag (it does).

The parliamentary debate over the new flag lasted 37 days. The Conservatives made 210 speeches (against it), the Liberals 50, the NDP 24, Social Credit 15, and the Créditistes nine. It was after midnight, Dec. 15, 1964, when the matter was finally settled after Pearson used the Parliamentary rule of closure to get his flag.

Pearson had hoped a new flag would promote unity, that Canada’s national emblem would be less Britain-centric, more inclusive. “If this is his idea of unity,” said an editorial in Vancouver’s The Province, “it is doubtful whether the country can swallow much more of it.”

Diefenbaker agreed. “You have done more to divide the country than any other prime minister,” he raged. When he died 15 years later, his coffin was draped with both the new flag and the Red Ensign.

But generations of Canadians have since grown up with the Maple Leaf. It has represented the country well. Simple, recognizable. It was what Donovan Bailey paraded after he won gold in the 100 metres at the 1996 Summer Olympics, what our athletes drape themselves in at global competitions. It grew on the nation. O Canada.

Advertisement