That day Canada lost an able administrator, Britain lost an insightful military strategist and the Canadian people lost a hero.

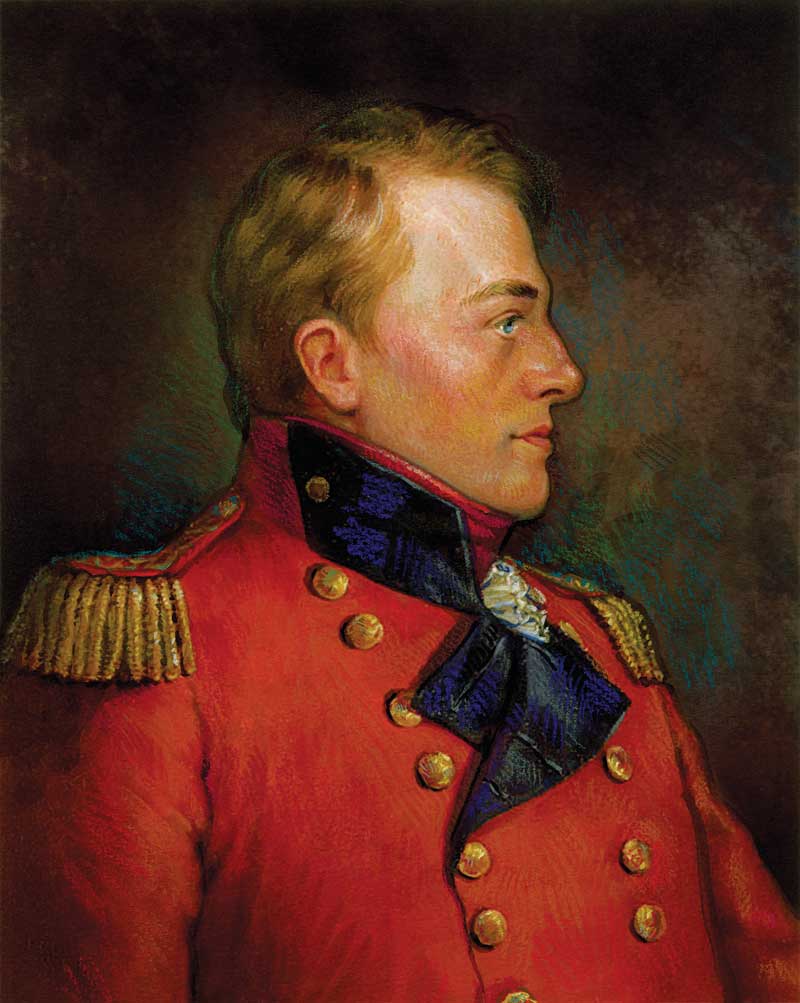

Born on Guernsey, an island in the English Channel, in 1769, he was the eighth son in a large family. Three of his older brothers went into the military and Brock followed at the age of 15, becoming an ensign with the 8th Regiment of Foot.

He had an active early career, serving in Barbados and Jamaica and the war with Napoleon. As a lieutenant-colonel in 1797, he was given command of the 49th Regiment of Foot, where his ability to interpret enemy strategies was honed.

Soon after joining the regiment a comrade, also a professional duellist, challenged Brock.

The challenger was a dead shot and at six-foot-two, Brock knew he would be an easy target. He demanded the contest be evened. Instead of shooting from the usual distance, which gave his opponent an advantage, Brock insisted they fire across the length of a handkerchief. The challenger wisely declined and soon left the regiment.

Brock avoided a bullet that time, but was wounded two years later in a campaign against Holland.

“I got knocked down shortly after the enemy began to retreat, but never quitted the field and returned to my duty in less than half an hour,” said Brock of the incident.

Britain and France had been at each other’s throats since before Brock joined the military. Britain’s North American colonies were threatened by the fight and the 49th was sent to Canada in 1802.

The population of the U.S. was 10 times that of Canada at the time, but a larger proportion of Canadian residents were trained in arms.

In Canada, Brock decisively handled both a problem with desertion and a brewing mutiny. In 1806, he was given temporary command of troops in the colony and, with war on the wind, he energetically began improving defences, upgrading fortifications in Quebec and turning the Provincial Marine into a fighting force. By 1811, Brock had advanced to major-general.

Although he frequently asked to be reassigned in Europe, he eventually turned down the opportunity in February 1812 sensing that war was imminent.

Britain and France each prohibited trade with any nation that traded with its foe. The United States was caught in the middle, but sided with the French.

In addition to the impact on U.S. trade with Britain, the Royal Navy boarded American ships and impressed “British” sailors, even if they considered themselves Americans. And the northwestern states felt Britain was behind the growing Indigenous federation, which sought land and autonomy.

On June 18, 1812, the United States declared war on Great Britain. American leaders were confident they could wrest Canada away from Britain. Overconfident, as it turned out.

The population of the U.S. was 10 times that of Canada at the time, but a larger proportion of Canadian residents were trained in arms. And British North America was defended by British troops, seasoned by years of war with the French, and the Royal Navy, which at the time was the world’s largest and most powerful.

U.S. leaders also mistakenly believed most Upper Canadians would rally to the American cause.

Canada was better prepared for war, partly due to the prescience of Brock. The preparation paid off with two quick victories.

A force of British soldiers, Métis traders, voyageurs and about 400 Indigenous allies attacked and seized the U.S. post on Mackinac Island in Lake Huron on July 17.After “cool calculation of the pours and contres,” Brock set out with a small force to reinforce the garrison at Fort Malden, on the Canadian side of the Detroit River, arriving on August 13.

Here, two key events happened. Brock met Indigenous leader Tecumseh, who would prove to be a staunch ally; and Brock learned that U.S. General William Hull had hastily withdrawn from an attempt to invade Upper Canada in July. Hull had found Canadians unenthusiastic about joining the U.S. and was shaken by loss of two supply lines and hundreds of men to ambush. He withdrew to Fort Detroit.

“Confidence in the General was gone, and evident despondency prevailed throughout,” Brock reported later. A great judge of character, he decided to press the attack on the timid general, whose 2,500 soldiers were demoralized and short of rations.

Brock, outnumbered, led a force of 1,300 soldiers and 600 Indigenous warriors on Detroit. He tricked Hull into believing he had a much larger force; militia were dressed in British uniforms and Tecumseh’s forces noisily swept by the fort, then doubled back for a second pass.

“It is far from my inclination to join a war of extermination,” Brock wrote Hull, “but you must be aware that the numerous body of Indians who have attached themselves to my troops will be beyond my control the moment the contest commences.”

And Brock commenced it, firing off a cannon.

Hull surrendered.

The fight was nowhere near as easy on Oct. 13 in the Battle of Queenston Heights after U.S. General Stephen Van Renssalaer crossed the Niagara River.

Brock ordered an attack, and led the men in.

As he directed various units, Brock was wounded on the wrist by a musket ball but pressed on, only to be shot dead not long afterward.

Despite the death and wounding of senior officers, British forces prevailed.

More than 5,000 people reportedly attended Brock’s funeral on Oct. 16.

The uniform he wore in battle is on display at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa, its coatee marred by a small hole where the bullet entered his heart.

Advertisement