On Valentine’s Day 1950, the United States suffered the first of many Cold War ‘broken arrows’—a jettisoned nuclear weapon, in this instance lost in the crash of a Convair B-36 in northwestern B.C., during a mock bombing mission.

Plans called for the B-36 to fly non-stop for 24 hours from Eielson Air Force Base, about 40 kilometres south of Fairbanks, Alaska, along the Alaska panhandle and the coast of B.C., perform simulated bomb runs in California then continue on to Texas.

An airfield at Alaska’s Eielson Air Force Base in 1945. [Wikimedia]

From the start of the flight, things did not go well.

It was –40 to –45 C and some minor cold-related problems were noted before the aircraft took off. In the air, the crew was in constant radio contact with U.S. Strategic Air Command in Nebraska.

The bomber was carrying a heavy load and the engines became strained when ice began to accumulate on the fuselage. Seven hours into the flight, the crew reported three of the plane’s six engines were shooting flames and had to be shut down.

He said he saw it explode in mid-air.

That put a heavier burden on the three remaining engines; the aircraft was quickly losing altitude.

Captain Harold Barry told the crew to bail out. But they were under orders not to allow the nuclear weapon or its components to fall into enemy hands.

“The pilot said we had to bail out, but that before we did, we had to go out over the water and get rid of this nuclear weapon. So we did that,” said survivor Dick Thrasher in a media interview. He said he saw it explode in mid-air.

Barry set the autopilot to take the bomber out over the ocean. The crew bailed out over Princess Royal Island, across the strait from Haida Gwaii. Within minutes, 40 U.S. and Canadian aircraft were searching for the men.

A dozen were rescued by a fishing boat and a Canadian navy vessel, but five crew were missing, likely succumbing to hypothermia after landing in the frigid ocean waters.

Meanwhile, the bomber veered and flew about 300 kilometres inland before crashing on a B.C. mountaintop.

The search for the bomber began immediately. Royal Canadian Air Force aircraft were pulled off the search for another U.S. aircraft carrying 41 military personnel and three civilians that had disappeared after crossing the B.C./Yukon border three weeks earlier.

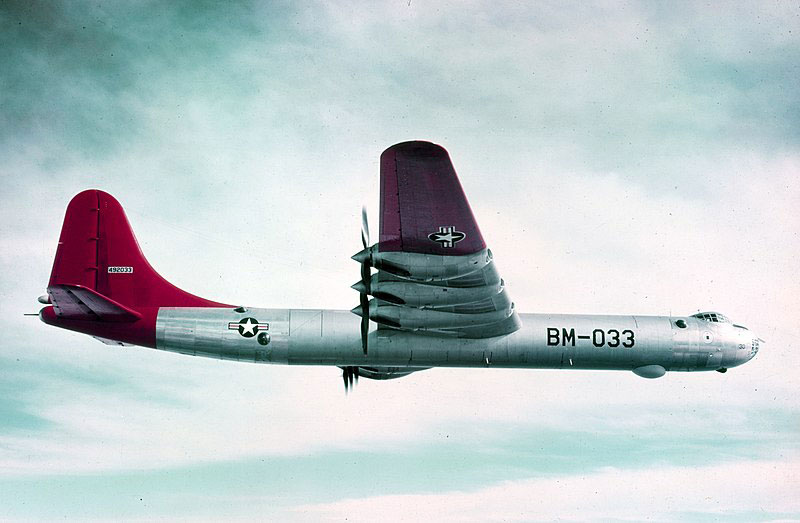

A Mark IV nuclear bomb was detonated—sans core—seven hours after the flight left Alaska. [Wikimedia]

In 1953, however, while the RCAF was searching for yet another missing aircraft, the wreckage of the bomber was spotted on Mount Kologet, about 80 kilometres east of the Alaskan border, in the wilderness northwest of Hazelton, B.C.

Wilderness and weather defeated the first U.S. air force teams sent to investigate that year. A team reached the site in 1954, retrieving classified components from the plane before blowing up the remnants.

The bomb’s uranium components were lost and never recovered. According to the U.S. Air Force, the plutonium core wasn’t present.

In 1997, the U.S. and Canada sent expeditions to check the site for environmental assessment. No radiation was found. The site was declared protected in 1998.

In 2016 a diver looking for sea cucumbers off the coast of Pitt Island discovered what was initially thought to be a piece of the atomic bomb, but that claim was dismissed as too far from the site where the crew reported dropping the bomb.

Five decades after the crash, partial remains of one of the crew members was recovered by a fisherman in 1952 and were identified as those of Staff Sergeant Elbert Pollard. The remains had been originally buried as a memorial to the missing flight’s crew in Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery in St. Louis, Mo. After his identity was confirmed by DNA analysis, he was reburied by his daughter in San Francisco National Cemetery in 2012.

Advertisement