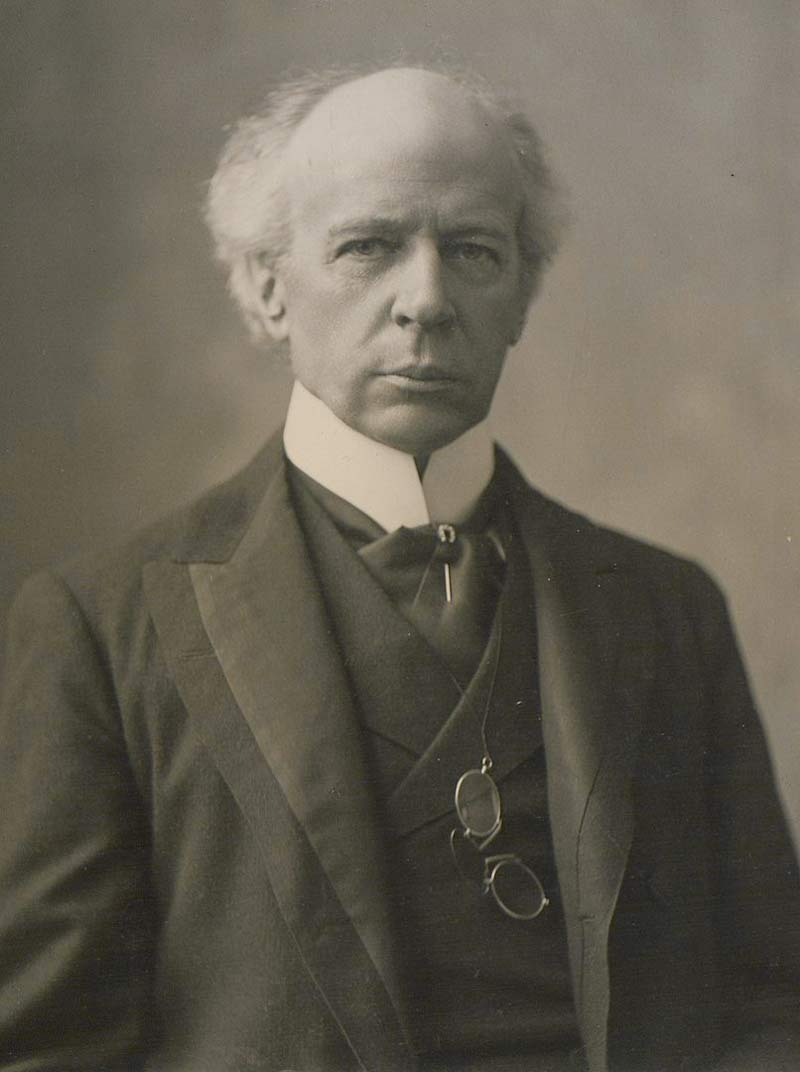

Wilfrid Laurier.[Wikipedia]

Laurier was a member of Parliament for 45 years, Liberal party leader for 32 and the country’s first francophone prime minister, a position he held for 15 years.

But it wasn’t political longevity that spurred as many as 50,000 people to file past his coffin, lying in state before the Speaker’s chair in the House of Commons Chamber, or to line up in deep snow and strong wind as his funeral cortege, with 10 sleighs carrying floral tributes, passed along Ottawa streets on Feb. 22, 1919. Extra passenger carriages were added to trains from Montreal and Toronto.

“No funeral in Canadian history, and few, we believe at any time in any country, has presented such a spectacle of national affection and grief,” said the Ottawa Evening Journal.

Laurier was admired, even by his political opponents, for his mastery of compromise and unceasing work to unite English and French Canadians.

Born in 1841, Laurier grew up in a political-minded family and, as a student, would skip school to listen to political speakers. He attended McGill College for law, which he practised before fearing it would lead to “anglification” of the country. “We are to be handed over to the English majority,” he complained.

“Few people at the turn of the century could resist his charm and courtesy.”

After Confederation, he settled in Arthabaskaville, a small Quebec town, where he opened a law practice and began a political career. He advanced through the positions of alderman, mayor, county warden, then was elected to the Quebec Legislative Assembly in 1871 and, three years later, to a seat as a member of Parliament. In 1887, Laurier was elected leader of the Liberal party.

“What an engaging personality!” wrote biographer Réal Bélanger. “Few people at the turn of the century could resist his charm and courtesy. When necessary, Laurier was able to abandon his prime ministerial ways for a simplicity that won over the most obdurate hearts.

“His disarming frankness despite his subterfuges, his exceptional honesty in a rather lax environment, his respect for others regardless of differences of opinion, his unshakeable loyalty to the Liberal cause and to his friends, his determination and firmness despite moments of discouragement and the limits already mentioned, all aroused the admiration of many Canadians.”

He supported free trade with the United States, arguing Canadian industries needed the large market to thrive and to keep people from emigrating south. But Conservative Prime Minister John A. Macdonald used this as a campaign issue, raising the spectre of annexation to the United States and saying it was an issue of loyalty to Canada and the Empire.

Laurier’s Liberals lost the 1891 federal election. But a political hot potato that resurfaced in the mid 1890s was to cement his reputation.

“If it were in my power, I would try the sunny way…of patriotism.”

In the early 1890s, Manitoba passed laws abolishing French as an official language and to create a publicly financed, non-denominational school system. This infuriated the Catholic Franco-Manitoban minority, who now had to finance its own school system if it wanted a religious education for its children but also had to pay taxes to support non-denominational education.

The Franco-Manitobans appealed to the federal government, on grounds the British North America Act, 1867, guaranteed funding of existing provincial denominational schools.

Since education is a provincial responsibility, the federal government refused to intervene. The case wended its way to the highest court of appeal, then the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in England. In 1895, the council decreed the federal government could intervene in the Manitoba school issue.

Laurier’s Liberals won the 1896 federal election. Some voters were drawn in by Laurier’s approach, others by his promise to honour provincial rights; some abandoned the scandal-plagued Conservatives. And Laurier had softened his stand on free trade in response to U.S. economic protectionism and a financial downturn in Canada.

He won the next three elections, remaining prime minister for 15 years—the longest consecutive tenure in Canadian history.

The first problem to land in Laurier’s lap after the election was the contentious Manitoba school issue. Rather than try to force through legislation requiring a change, Laurier proposed a diplomatic solution.

“If it were in my power, I would try the sunny way…of patriotism, (asking the provincial premier) to be generous to the minority in order that we may have peace among all the creeds and races…Do you not believe that there is more to be gained by appealing to the heart and soul of men rather than to compel them to do a thing?”

Laurier’s positive outlook worked to develop a compromise that left provincial laws standing, but allowed limited religious and French-language instruction in public schools where there was sufficient demand.

Compromise became the hallmark of his style. He won the next three elections, remaining prime minister for 15 years—the longest consecutive tenure in Canadian history.

“With his exceptional charm and charisma, Laurier could convince, captivate, and listen to each individual as at that moment the most important person in the world,” wrote Bélanger.

“He also fell back on his habitual easygoing manner, both to gain respite from the fiery furnace he faced every day and to let time do its work [he was] skilful, opposed to taking rigid positions, and occasionally manipulative.”

When Britain wanted Canada to send troops to the South African War, which was supported by English Canadians and opposed by French Canadians, Laurier’s compromise was to send a contingent of volunteers. When there were demands Canada send men to the Royal Navy, his compromise was to create the Canadian Navy.

Laurier, towards the end of his tenure. [Wikipedia]

Campaigning on the issue of free trade, Laurier’s Liberals were defeated in 1911, and again in 1917, when the issue of conscription was threatening national unity.

He was working on revitalizing the party when he fell and hit his head and subsequently suffered a stroke. He died on Feb. 17, 1919.

A century later, Wilfrid Laurier University is studying his complex legacy—while he was seen as a nation builder his government also implemented policies now deemed racist and discriminatory.

The $100 Chinese head tax was introduced in 1900 during Laurier’s tenure. He also signed an order-in-council (that did not come into law) banning Black immigrants. And the federal government continued to fund residential schools through his term in office and beyond.

“The Laurier Legacy Project will take a critical and research-based look at the histories of Sir Wilfrid Laurier, his era, and our institution,” said Barrington Walker, the Waterloo, Ont., university’s associate vice-president of equity, diversity and inclusion. “Our ultimate goal is to reflect upon our current-day values and our future.”

Advertisement