An original German bunker from the First World War stands near the south end of the Langemarck German cemetery near Ieper, Belgium, known during the war as Ypres. More than 44,000 German war dead are buried here.[Stephen J. Thorne]

‘The remains of more than 25,000 German war dead rest in a mass grave alongside the entrance to Langemarck German war cemetery. The names of almost 17,000 unidentified dead are listed on bronze tablets surrounding the burial mound.

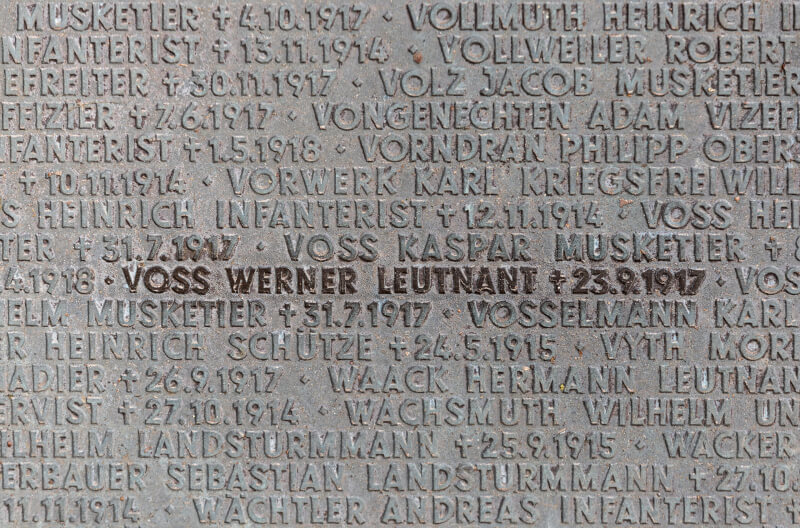

German ace Werner Voss’s remains were lost after he was shot down over Passchendaele in 1917. His name appears on the memorial wall at Langemarck. [Stephen J. Thorne]

The tablets are punctuated by scattered groupings of the distinctive German crosses of the day.

But the focal point of this impressive site where the German advance ground to a halt in the autumn of 1914 are the graves of some 3,000 German youth, many of them students, killed during a relatively insignificant—indeed, futile—battle that became the stuff of myth and legend.

The names of the first 6,000 Langemarck burials are listed on oak panels that form the walls of a serene space inside the German sandstone block at the cemetery entrance. A banner proclaims Ihren Kameraden Komilitonen Die Deutsch Studentenschaft (your comrades, fellow students, the German student body.) Some of those killed were just 15.

The oak walls of the sandstone entrance to Langemarck bear the names of Langemarck’s first 6,000 burials. [Stephen J. Thorne]

der Führer was a gefreiter (lance corporal) during the Great War. The founding commander of his Bavarian 16th Reserve Infantry Regiment, Colonel Julius von List, was killed in 1915 and is buried at Langemarck.

Traditional German crosses stand among the tablets bearing the names of soldiers killed during WW I fighting in the Ypres Salient. [Stephen J. Thorne]

The invaders’ race to the sea, and the Channel ports they coveted, by all accounts was already a lost cause when the German chief of staff, General Erich von Falkenhayn, ordered one last push in an attempt to gain better defensive positions and preserve German military prestige.

“The Ypres area became their last hope to prevent a stalemate before winter, so in the last weeks of October and the first weeks of November, they are using all available resources to break through,” explained Erwin Ureel, a Belgian military veteran and Flanders battlefield guide.

“It’s in this period that the exhausted remainders of the Belgian Army are flooding the coastal area north of the Ypres Salient, leaving the Ypres/Passchendaele area as [the Germans’] last possibility to outflank the British and French troops.”

Erwin Ureel served in the Belgian military and now conducts private tours of wartime battlefields. [Stephen J. Thorne]

More attacks followed. All failed, until Bixschoote, a small French-defended village a little more than four kilometres west of Langemarck, fell on Nov. 10.

Despite this minor victory, the last-ditch effort in Germany’s run to the coast instead marked the beginning of a war-long stalemate on the Western Front. But that not-insignificant fact, along with the name Bixschoote, would be all but lost to the German populace, thanks to a communique issued by the Oberetse Heeresleitung (German high command) the following day.

Translated, it said: “West of Langemarck, youth regiments singing ‘Germany, Germany Above All’ advanced on front-line enemy positions, broke and took them. Approximately 2,000 French line infantry and six machine guns were captured.”

Mighty oaks rise above the German graves at Langemarck. [Stephen J. Thorne]

Langemarck, which today is spelled without the ‘c,’ sounded more German than Bixschoote (now known as Bikschote), and thus became entrenched, so to speak, in the German psyche despite the fact it was a resounding defeat.

“The losses of Langemarck came to symbolize German heroism, patriotism and a spirit of sacrifice, accentuated in the increasingly embellished accounts of how German troops had assaulted English machine guns without cover,” wrote historian Lukas Grawe. “A military fiasco was thus reinterpreted as a moral victory.

“The assertion that the German regiments had sung the ‘Deutschlandlied’ while attacking played the leading role in the genesis of the myth.’

Brick farms were rebuilt from the signature clay that is the Flanders hallmark. [Stephen J. Thorne]

“It was a useful myth for a defeated nation” says the Langemark-Poelkapelle municipality website. “In nationalist circles 11 November—Langemarck Day—became a fixture in the calendar and an antipode to…Armistice Day.”

The Langemarck cemetery grew postwar as Germany consolidated most Belgian battlefield burials there and at three other sites: Menen (47,864 German graves), Vladslo (25,644) and Hooglede (8,241).

The Nazi regime finalized the cemetery design in the 1930s, when it re-elevated the myth of Langemarck as a propaganda tool to, as Ureel put it, “motivate the German youth for their national-socialist imperial dream.”

Langemarck became a rallying point for middle-class, nationalist youth and a catchphrase for the political right. It remained an inspiration for commemorative celebrations, youth organizations, schools and National Socialist study programs.

The main building built for Hitler’s 1936 showcase Olympic Games in Berlin was called Langemarckhalle. It still stands, “a tribute to the volunteer and reserve regiments, who, inadequately trained and armed, suffered devastating losses during the battle of Langemarck near Ypres, in the Belgian province of West Flanders, on November 10th, 1914.”

Dutch soldiers survey a map of the Ypres Salient as it appeared during war. [Stephen J. Thorne]

At the cemetery, a portion of the trench from which German soldiers first released chlorine gas against French colonial troops during the Second Battle of Ypres on April 22, 1915, runs through the parking lot.

Overlooking the site is a monument by German sculptor Emil Krieger of four mourning figures, added in 1956. Several original German bunkers still stand toward the south end of the grounds.

The Langemarck cemetery is maintained by the German War Graves Commission, the Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge.

The names of almost 17,000 unidentified dead are listed on bronze tablets surrounding the mass grave at Langemarck. [Stephen J. Thorne]

This is the latest in a series on the war in Flanders. Next week, the evolution of the uniform in WW I.

Advertisement