The Permanent Active Militia (or Permanent Force) began the Great War in 1914 with a strength of a little more than 3,100 officers and men. After reorganization at the end of the war, the Permanent Force (PF) was limited to 5,000, though it never reached that figure. In 1939, on the eve of another war, the PF had some 4,260 in all ranks, and many were too old, or too unhealthy, for overseas service. Canada’s regular soldiers were no more ready for the Second World War than they had been for the First.

Why? In 1919, the Canadian public perceived that the military was unnecessary, too costly and too much a reminder of the terrible losses overseas from 1915 to 1918. The government agreed, funding the army to the tune of a mere $11 million in 1921 and reducing that sum yearly to under $9 million by 1934.

Canada barely had a military, but the barebones PF existed nonetheless. Its infantry and artillery units had no modern equipment and little ammunition, its cavalry had begun to lose its horses and it had no tanks at all.

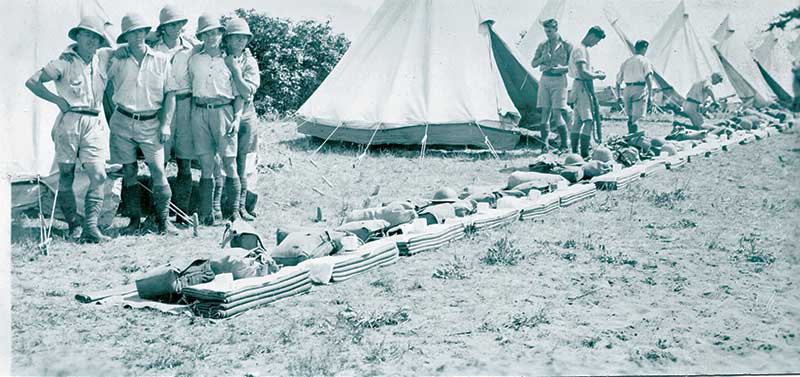

The Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, one of the Permanent Force’s three regiments, conduct kit inspection at Camp Hughes, Man., in 1928.[Courtesy The PPCLI Museum and Archives/P50(105)-1]

Even so, the PF had its roles. Each year, it provided some 250 officers and non-commissioned officers to assist the Non-Permanent Active Militia units, a difficult task because they were almost completely untrained and had only Great War weapons and uniforms. And Ottawa couldn’t fund much training time either. Plus, the militia officers, many young businessmen, scorned the PF.

A Seaforth Highlander recalled his “poor opinion of the PF in the 1930s. They had too little to do, spending too much time at the bar which upset the ‘working professionals’ in the Seaforths. They were lazy, sloppy and didn’t think or work like militia officers.” Another junior officer in a Toronto regiment said “the PF were seen as poseurs and the Royal Military College graduates were scorned and resented” because they were know-it-alls. For its part, the PF thought little of the “bloody militia,” seeing them as incompetents playing at being soldiers.

The Permanent Force units, however, also played at soldiering. All were understrength and most were only able to muster one or two companies, batteries or squadrons. The infantry had three regiments—the Princess Patricia’s, the Royal Canadian Regiment, and the Royal 22e Régiment—and only the artillery, even with obsolete guns, was anything close to efficient.

Artillery officers had technical expertise and some had advanced training. They worked closely with militia units, a few of which were also efficient. Still, the sole interwar field exercise that brought the PF’s arms and services together in 1938 was described as a shambles.

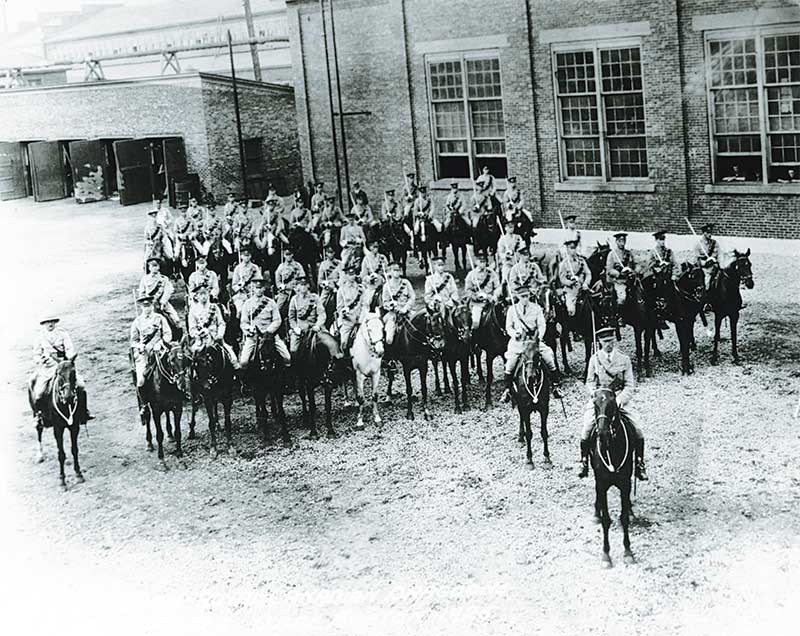

The Royal Canadian Dragoons support local law enforcement during the strike at Sydney Mines, N.S., in 1925.[Beaton Institute/87-964-17494]

Canada’s regular soldiers were no more ready for the Second World War than they had been for the First.

There was some good work, however. Ambitious officers wrote examinations for admission to the British Army’s Staff College. The school provided advanced training in command over a two-year course and let officers see large units in the field (something impossible in Canada). The PF sent four captains a year—63 between the wars in total—to the program.

General Andrew McNaughton, pictured here in the 1920s, was the PF‘s rising star.[LAC/PA-034180]

There was also the Imperial Defence College (IDC) in London that offered a one-year course on high strategy and international politics to brigadier-generals. Canada sent 20 officers to the IDC, a group that included Andrew McNaughton and Harry Crerar (both army commanders in the coming war), E.L.M. Burns (a corps commander) and Maurice Pope (the military adviser to the Prime Minister).

The PF also ran staff training courses for militia officers, which raised standards. Still, if the Staff College education was equivalent to fourth-year university, the Militia Staff Course was like first-year, one PF officer said later.

The handful of Permanent Force officers at headquarters in Ottawa, meanwhile, focused on administration and planning. The tiny Directorate of Military Operations and Intelligence was the hub, drafting plans for contingencies ranging from war with the United States or Japan to sending an expeditionary force to fight with Britain against “a civilized enemy.” In 1920, Colonel J. Sutherland (Buster) Brown’s first task was to create Defence Scheme No. 1.

Men work on a relief camp in Wagaming, Ont., in 1935, and break for lunch at a similar facility in Lac Seul, Ont., in 1933. The PF oversaw the program.[DND/LAC/e999902290-u]

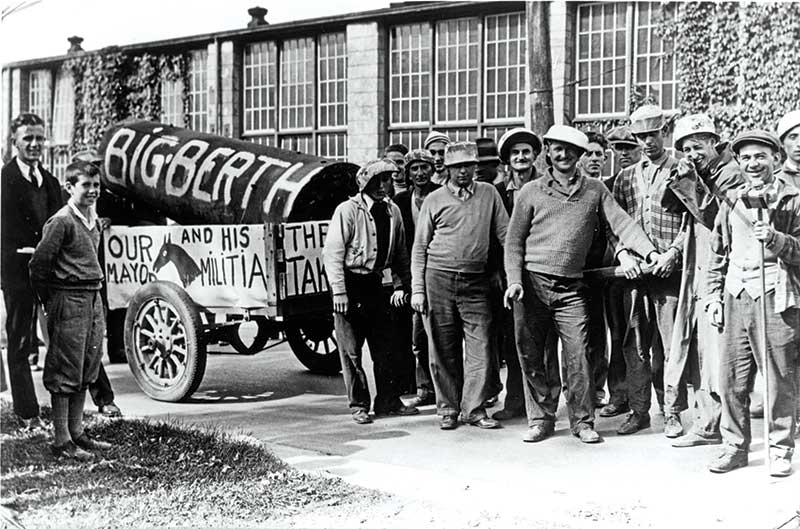

Strikers in Stratford, Ont., mock the PF’s presence in 1933.[Stratford-Perth Archives]

This northern role won the PF substantial credit with the government.

Brown’s plan set out the army’s role for a war with the U.S. It has usually been portrayed by historians as madness. It wasn’t. The Americans had similar plans to attack Canada, and although Britain and the U.S. had been allied during the Great War, no alliances were permanent.

Brown’s proposal called in part for an advance “into and [to] occupy the strategic points including Spokane, Seattle and Portland,” for forces to “converge towards Fargo in North Dakota,” and to move toward Minneapolis. All this made sense of a sort—if help from Britain was coming, the army might be able to disrupt American plans long enough for assistance to arrive. But Brown somehow believed that the untrained militia could move into the U.S. and succeed against the almost equally untrained, but larger, National Guard and regular U.S. army. That was madness.

More realistic was the plan to dispatch an expeditionary force to assist Britain in a war in Europe. Brown’s draft, refined and developed during the interwar years, initially called for a seven-division force. By the late 1930s, under pressure from the Liberal government, home defence became the priority, but the plan to dispatch a two-division field force remained intact until the fall of France.

Another PF task in the 1920s and 1930s was to intervene in labour-management disputes. Lieutenant Guy Simonds, serving in the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery (RCHA), was deployed to Sydney Mines, N.S., in 1925 to provide aid to local authorities in preventing violence during a strike by miners.

Initially, the strikers “were very hostile to the troops,” wrote Simonds later. They hurled stones and insults at the soldiers. But over time, Simonds said the PF was able to convince them “that we were not on anybody’s ‘side’—we didn’t represent the owners, but were there to protect lives and property.”

The RCHA created a soccer team and challenged the miners to a game, which broke the ice. The violence ceased, and when the RCHA left, “the miners and their families lined the streets and cheered us…” said Simonds. His report was likely rose-coloured—company police had killed one striker—but the RCHA had been more even-handed and killed no one.

Nor did anyone die at the hands of the PF in the 1933 general strike by unionized furniture workers and chicken processors at Swift’s meat plant in Stratford, Ont. The mayor requested military assistance, and Ottawa sent in the Royal Canadian Regiment from nearby London, some riding in Carden-Loyd machine-gun carriers (the PF’s only armoured vehicles) as a show of force.

The carriers saw no action, the soldiers remained in the armoury, the strike ended peacefully and Stratford marked the last time the military was called on to intervene in a labour dispute between the world wars.

The PF also worked in the Canadian North, which in the 1920s was largely disconnected from the rest of the country. In 1923, the Permanent Force’s tiny Royal Canadian Corps of Signals—its strength no more than 150 officers and men—was directed to establish the Northwest Territories and Yukon Radio System to provide reliable communication to the “outside.” Private William J. Megill, a 16-year-old soldier, went to Mayo, Yukon, in 1924 to help operate the radio station there. Megill recalled enjoying his four years in the North because promotion was rapid (he was soon a staff sergeant) and there was a northern allowance of $1,000 a year, plus a messing allowance of 50 cents a day. That allowed him to save money even though his initial pay was only 75 cents a day.

The radio system soon expanded and, in 1938, set up a radio-telephone service. This northern role won the PF substantial credit with the government.

While a northern posting might have been sought after, “relief stiffs” in government camps for unemployed men during the Depression were not. The concept had been suggested to Prime Minister R.B. Bennett in 1932 by General McNaughton, then Chief of the General Staff. Alarmed by the numbers of homeless men, many of them veterans unable to find work, the opportunistic McNaughton believed the camps could instill some purpose in a restless group and help limit growing revolutionary sentiment.

Provided with lodging, food, clothing and medical care, and paid 20 cents a day for their work, the camp residents could clear ground for airfields, highways and military bases, which McNaughton saw could benefit the massively underfunded Department of National Defence. The PF provided most of the personnel—in civilian clothes—to run the camps.

While well-intentioned, the hastily created camps eventually offered rough, inadequate conditions to some 170,000 men—who dubbed themselves “the Royal Twenty Centers,” a reference to their pay. The PF, meanwhile, suffered for its efforts to manage the men who were unhappy with their lot and their treatment.

In 1935, more than 1,000 of the campers went to Ottawa to protest the scheme.[LAC/C-029399]

After the 1935 On to Ottawa Trek, which was made up of more than 1,000 unemployed men who had ridden boxcars eastward in protest of the camps, the Prime Minister sacked McNaughton as defence chief. Bennett lost the election nonetheless, and the victorious Mackenzie King quickly closed the camps. If the radio system had helped the PF, the relief camps damaged its reputation.

Canada’s army was completely unprepared for war in 1939. Still, there were some capable officers in the Permanent Force, men such as McNaughton, Crerar and Burns, all able Great War veterans, and younger leaders like Simonds. Given how the government and public had scorned defence after 1919, the country was fortunate it had such skilled military men.

Advertisement