Bombadier: G.M. Hart, Royal Canadian Artillery, attends to some uniform wear and tear in Ossendrecht, Netherlands, 1944.[LAC PA-143931]

Sewing kits were a surprisingly

versatile tool for soldiers in the field

versatile tool for soldiers in the field

At fleet school they said, ‘If we wanted you to have a wife, we’d issue you with one,’” recalls navy veteran Jim Ross. “And then they did.”

In his six months at Canadian Forces Base Cornwallis in Nova Scotia in 1958, Ross became intimately familiar with his housewife—a sewing kit with everything he needed to keep his uniform shipshape.

“We had to sew our names on everything we were issued with,” said Ross, who lives near Charlottetown. “That was a big thing. It took up so much time because we had so much kit…summer uniforms, winter uniforms, shorts and underwear and everything. Hats.”

That navy-blue housewife, with his name and service number neatly embroidered in red on the outside flap, now resides in the Veterans Memorial Military Museum in Kensington, 50 kilometres west of Charlottetown. A few minutes rooting around in displays and museum chairman Dean Cole also identifies housewives issued to Canadian troops from the First World War and Second World War.

A Union soldier repairs a uniform in this stereograph of camp life during the U.S. Civil War. [Library of Congress 1s02987]

Like recruits throughout history, Ross soon learned he was responsible for keeping his uniform in good nick. Ancient soldiers carried a leather bag with the necessary tools and supplies. The pocket sewing kit—nicknamed the housewife and shortened to hussif or hussy—came along in the mid-1700s. In an era when women swooned over men in ornate and colourful uniforms, mothers, wives, sisters and sweethearts often provided their heroes with homemade sewing kits showing off their own needlework skills. Soldiers tucked away personal mementoes in the handy pockets. During the Civil War in the United States, which predated dog tags, these mementoes were often the only way to identify casualties.

During the world wars, Canadian-issued kits contained a variety of buttons and needles, thimble, thread for sewing up rips and sewing on buttons and badges and thicker thread for darning socks and gloves, beeswax for waterproofing thread and swatches of cloth for patches. But women’s groups and family members continued to make sewing kits for use at the front or for Red Cross packages.

A rust stain is the only evidence of the needle in the sewing kit used at sea during the Cold War by navy veteran Jim Ross. [Sharon Adams]

One such kit brought home comfort for Royal Canadian Air Force Flying Officer George Sweanor from Port Hope, Ont., a newlywed shot down in 1943 while serving with Bomber Command and sent to a prisoner of war camp. “My November birthday was made more memorable by the arrival of Joan’s parcel…. I cherished the sewing kit because she made it from the same material that she had used to make her dressing gown,” he writes in his memoir, It’s all Pensionable Time: 25 Years in the Royal Canadian Air Force.

This housewife used during the First World War by an infantry lieutenant can be found in the Canadian War Museum. [Sharon Adams]

Australian soldier Henry John Harris wrote about an inventive use for his kit in his First World War memoir on the website www.ww1.canada.com: “Owing to the extreme cold conditions and as there were a store of sandbags in the pillbox, I decided to sew several of the sandbags together to make a blanket, and believe me those sandbags did keep me and a cobber [comrade] warm for the four nights we stayed in that pillbox.”

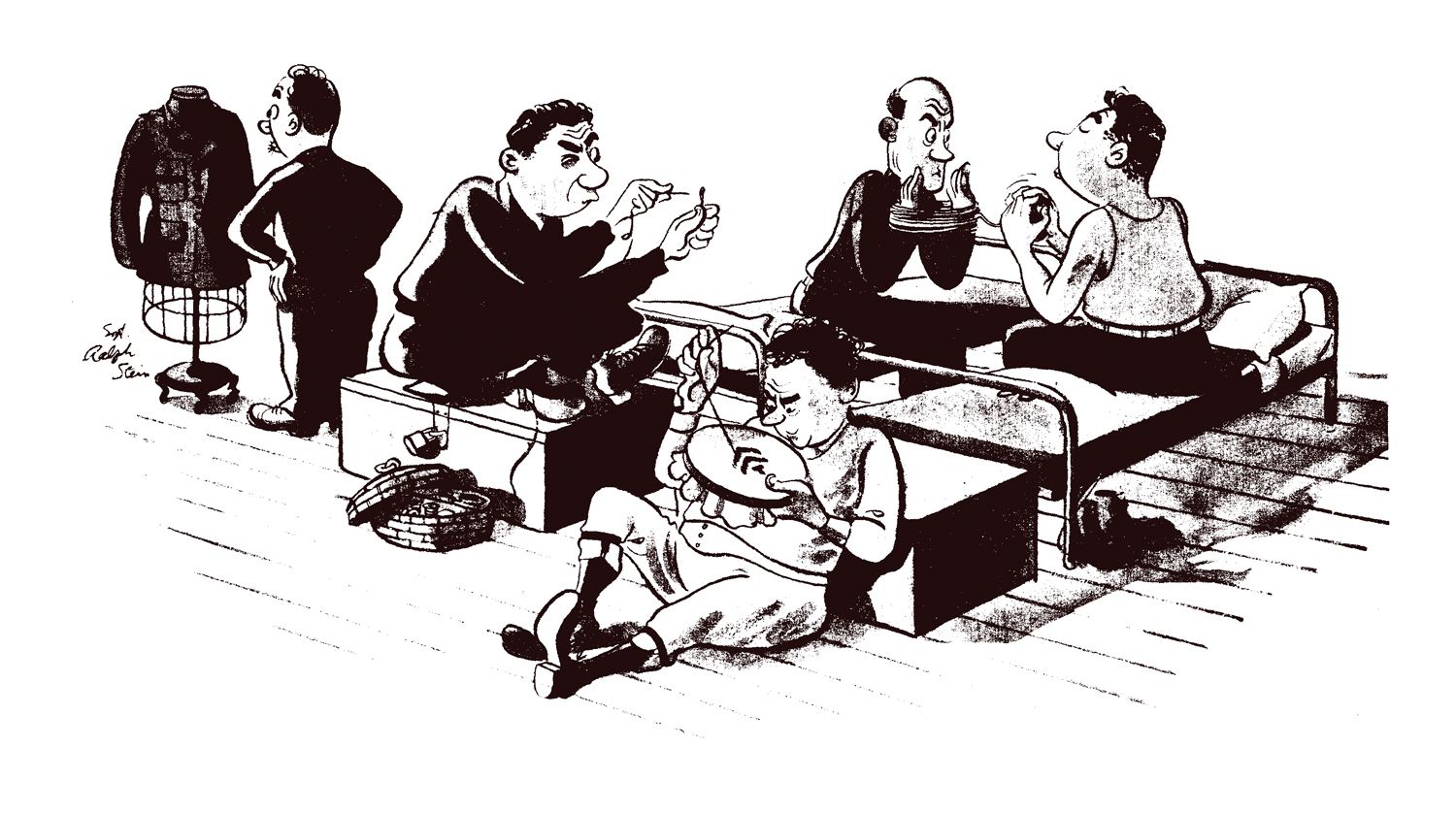

A sergeant sews on his own stripes in this cartoon by Sgt. Ralph Stein illustrating a how-to article for YANK, The Army Weekly in 1943.

The kit came in handy for Sergeant Ryan Davidson of the Department of National Defence’s Directorate of History and Heritage, in the 1990s. “I had to sew on my own rank insignia after being promoted in the field.”

Ross, undoubtedly like many other veterans, admits he is no longer a dab hand with a needle and thread. He chuckles. “I’ve got a real housewife now”—Marion, his wife of 52 years.

Advertisement