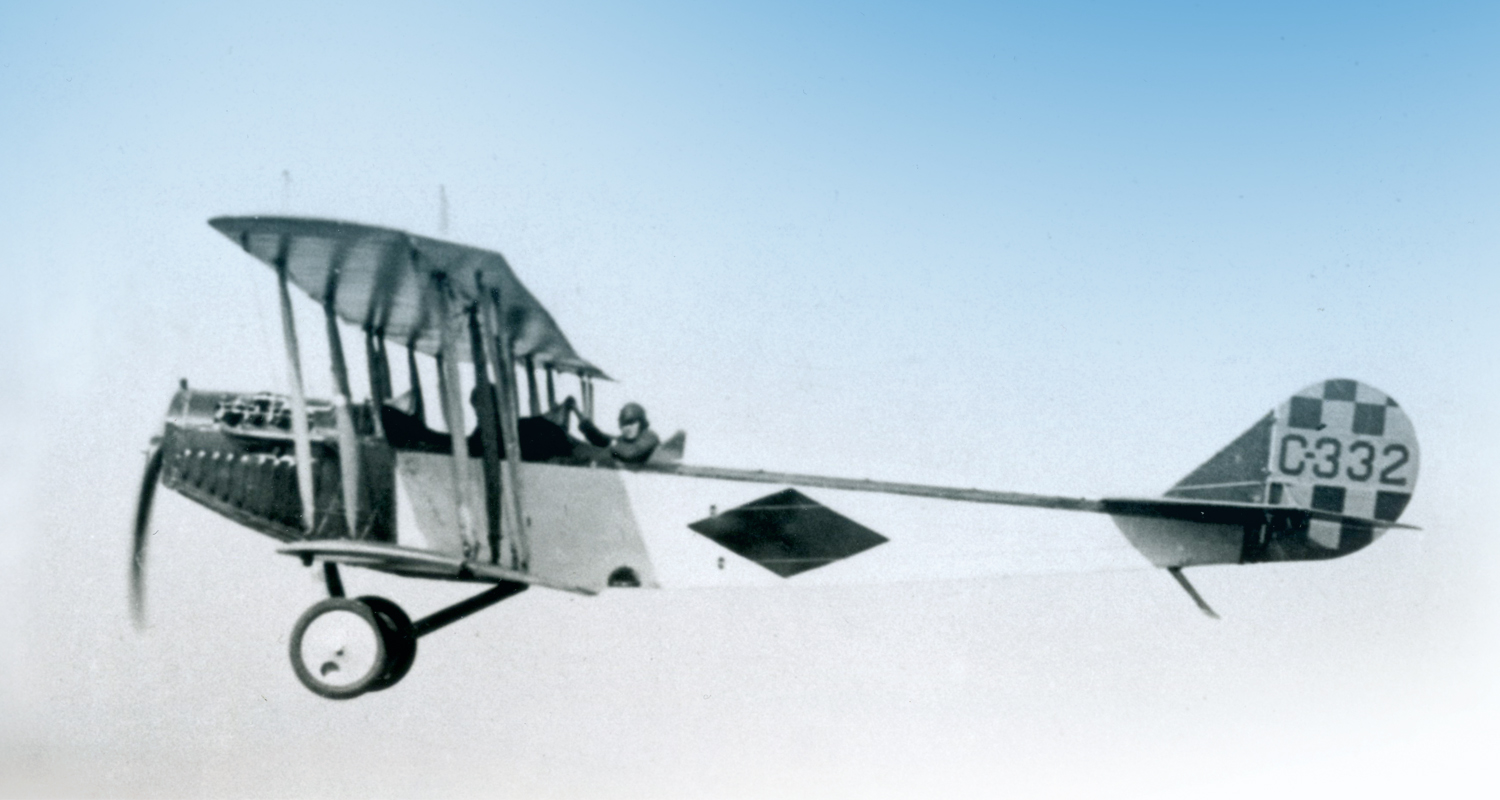

A recruit trains on a JN-4 at the School of Aerial Gunnery in Beamsville, Ont., in 1918. [DND/LAC/PA-022924]

In 1917 and 1918, the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and its successor, the Royal Air Force (RAF), directed an ambitious flight training operation in Canada. The scheme had no precedent, but it inspired later, similar schemes—the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (1939-1945) and a general program to train North Atlantic Treaty Organization aircrew at Canadian centres from 1952 onwards.

The importance of air power had been growing from the outbreak of the First World War. Aircraft mapped enemy trench systems, directed the guns shelling those trenches, and warded off opponents’ machines intent on performing the same tasks. As aircraft became more vital to waging war, Britain required greater numbers of airmen. Late in 1916, an RFC expansion plan suggested formation of 35 new training squadrons. Most would have to be located outside of Britain itself due to lack of space for more airfields and the need to tap external aircraft production capacity. Those requirements were the genesis of the RFC/RAF Canada training program of 1917-18.

As early as December 1914, Canadians had begun to enter the RFC and the Royal Naval Air Service, some by enlistment in Canada, most by overseas transfers from the Canadian Expeditionary Force. The process had commenced as a trickle but, by late 1916, it had become a steady stream. Paradoxically, Canadian governments had no air policy before the First World War and precious little until 1918. They did not hinder British recruiting efforts in Canada, but neither did they promote air training at home. Faced with this official apathy, yet anxious to secure Canadian resources for the RFC, British authorities adopted a policy best described as, “If you want it done—do it yourself.”

It provided training up to the advanced level

where pilots were almost—but not quite—ready

to participate in combat.

The training program that emerged had minimal Canadian government participation but much assistance from the Imperial Munitions Board (IMB). Established in 1915 to co-ordinate shell production and other military contracts in Canada, the IMB was composed of Canadians—yet it was essentially a British organization, paid for chiefly by British taxpayers (though supplemented by loans from the Canadian government). It was an example of the flexibility in economic and military affairs within the British Empire. The IMB secured land for air training, arranged construction of barracks and hangars and established Canadian Aeroplanes Ltd. as a factory to manufacture Curtiss JN-4 trainers for the program. The RFC/RAF provided the direction including syllabi, uniformed managers, and instructors in dozens of specialist trades including armament, gunnery, aircraft maintenance, navigation and flying itself.

Lieutenant-Colonel (later Brigadier) C.G. Hoare, an Imperial officer, arrived with his advance staff in January 1917.

Hoare and his team set about organizing the plan. With buildings still under construction and the first production JN-4s accepted only on Feb. 22, he ordered that flying instruction commence at Long Branch, Ont., on Feb. 28, 1917. The largest school, Camp Borden, launched flying training on March 30, 1917. The Canadian enterprise included a vigorous recruiting campaign which featured newspaper advertisements; the illustrations were the work of F.H. Varley. A comparable scheme in Egypt was instructional only, without active enlistment efforts.

The program grew monthly as new schools were opened and more pupils arrived. At war’s end, the organization occupied quarters throughout Ontario at Hamilton (Armament School), Toronto (School of Military Aeronautics, Recruiting Depots), Long Branch (cadet ground training), Beamsville (School of Aerial Gunnery, renamed School of Aerial Fighting), Armour Heights (pilot training, School of Special Flying to train instructors), Leaside (pilot training, Artillery Co-operation School), Camp Rathbun (Deseronto, pilot training), Camp Mohawk (Deseronto, pilot training) and Camp Borden (pilot training). The quarters occupied included former schools, a prison and much of the University of Toronto.

One should view the plan in the context of global RAF operations. The Canadian organization was equivalent to what the British would have called a Training Brigade. It provided training up to the advanced level where pilots were almost—but not quite—ready to participate in combat. The finishing touches would be applied at advanced schools in Britain or France.

The training itself grew more sophisticated with Canadian experience, “feedback” from the Western Front and revised British training procedures. The most important changes came with adaption of the Gosport System developed in Britain by Major Robert R. Smith-Barry and in general use by 1918; the name derived from the school where he devised and then propagated his theories. Originally, flight training had told pupils very little about why an airplane behaved as it did, and instruction concentrated more on what to avoid. The Gosport System taught the dynamics of flight, then moved on to how to use the airplane. For example, earlier pupils had been warned to avoid spins; those of 1918 were taught how to get into a spin and then recover from it.

RFC authorities envisaged recruiting ideal candidates, described as “the clean-bred chap with lots of the devil in him, a fellow who had ridden horses hard across country or nearly broken his neck motoring or on the ice playing hockey.” What they got was more mundane—a keen, healthy specimen of middle-class Canadian youth. The largest group of air-minded volunteers were students (28.2 per cent), representing an unknown proportion of the populace. The average age on enlistment (or transfer from another service) was 23. Fewer than a dozen volunteers mentioned having “previous aeronautical experience.”

Their basic flight trainer was the JN-4 (Can), an American design modified by Canadian Aeroplanes Ltd. to meet military training needs, notably by removal of a wheel control and substitution of a joystick. JN-4s were also adapted to accommodate camera guns, reconnaissance cameras and machine guns; at least one was modified to be an aerial ambulance. If the JN-4 had a fault, it was that the type was too easy to fly and did not challenge cadets. Had the war extended into 1919, JN-4 production would have been superseded by construction of the more advanced Avro 504K. As it was, only two of the newer aircraft were built by Canadian Aeroplanes before the Armistice.

William Stanley Lockhart was a typical trainee of the late war period. A native of Moncton, N.B., and a graduate of McGill University, he had been working as an electrical engineer in New England but returned to Canada in 1917 to join the Royal Flying Corps. He received initial ground school training at the School of Military Aeronautics (Toronto). By the time he had mastered such subjects as Military Law and Theory of Flight, the relocation of some training to Texas had occurred. His first flight on Dec. 21, 1917 was essentially a 20-minute “joy ride” around the airfield with an instructor. The next day he made two flights, totalling 25 minutes, at No. 88 Canadian Training Squadron in Armour Heights. Two days later he flew for 25 minutes. Much of his instruction was simple “touch and goes”—takeoffs and landings. On Dec. 30, for example, he made five landings in a 35-minute session. Finally, on Jan. 7, 1918, after seven hours and five minutes of dual instruction, he was allowed to go solo. Two days later, making another solo flight, he crash-landed and wiped out the undercarriage.

Most of his flying thereafter was solo, and, on Jan. 18, he was permitted to take the JN-4 up to 8,500 feet in a flight lasting 75 minutes. His logbook entry for Jan. 19 reads “Forced landing” but it is unclear whether this was a training exercise or a real emergency. He made his first cross-country solo on the morning of Jan. 23, 1918; that afternoon he was airborne for 95 minutes, engaged in formation flying for the first time. Subsequent log entries recorded tactical exercises, “Photography” (Jan. 26), “Puffs” (artillery spotting, Jan. 28), “Ground strips” (visual communications with the ground, Jan. 29) and finally, “Bombs” (Feb. 2). With 39 hours and 20 minutes flying in his log book, he was graded as a pilot and posted overseas.

However, he was not yet trained to operational standards. Fresh instruction began on May 1, 1918, with No. 34 Training Squadron (Chattis Hill, Hampshire), first on Avro 504s, then Bristol single-seat Scouts with extensive aerobatics and “fighting practice.” Finally, on May 28, 1918, he flew a real combat machine—a Sopwith Camel. At the beginning of July he went to No. 4 School of Aerial Fighting (Freiston). At the end of July, he was posted to the Royal Navy Air Station at East Fortune. He was being trained to take off from platforms mounted on cruiser gun turrets. Lockhart recorded His Majesty’s Ship Pegasus and HMS Sydney in his logbook, with a flight from the latter on Oct. 12. However, the war ended before he saw action. He was repatriated to Canada and demobilized July 1919.

Aerial instruction was supplemented by intensive ground training in classrooms, at gun butts, and even with training aids that included battlefield models and primitive flight simulators. By any standards the program was sophisticated, even dealing with such topics as aviation medicine and psychological screening of candidates.

With virtually no experience in severe cold weather flying, RFC authorities feared that training might be shut down entirely for the winter of 1917-18. Earlier private schools around Toronto had operated only in summers. Consequently, a large portion of the program was relocated to Fort Worth, Texas, where it also trained many Americans and led to mutual exchanges of information on training methods. Those training squadrons left in Canada adapted their JN-4s to cumbersome skis, worked out special formulas for lubricants and kept the system operating at least as well as the organization in Texas, where mud proved as frustrating as deep snow.

Overall, the training scheme enrolled 9,200 cadets. Of these, 3,135 completed pilot training and more than 2,500 were sent overseas; the balance of graduates were either retained as instructors or awaiting postings to Britain when the Armistice was signed. In addition, 137 observers were graduated, of whom 85 were sent overseas. The program also turned out at least 7,400 mechanics. A number of American personnel (navy as well as army) were trained in Canada, as well as four or five White Russians.

The results were achieved at some cost. At least 129 cadets and some 20 instructors were killed in flying accidents. A particularly nasty instance was a head-on collision at Beamsville on May 2, 1918. One instructor was shaken up and the other had a broken hip; the two pupils in the front cockpits took the full force of the impact and were killed. Yet the safety record improved as time went by; in April 1917 there was one fatality for every 200 hours flown, in December 1917 one fatality for every 1,500 hours, and in October 1918 one fatality for every 5,800 hours flown. The most publicized accident of the program actually involved no injuries; a JN-4, attempting a forced landing on Oshawa’s main street on April 22, 1918, became entangled with telephone wires and wound up pinned to a large storefront where it remained suspended for several hours. Photographs of the bizarre crash turned up in every history of the plan.

RFC Canada graduates of the plan began sailing for Britain as early as June 1917. Probably the most famous was Lieutenant A.A. McLeod, who trained at Long Branch and Camp Borden, received his wings in July 1917, and reported to No. 2 Squadron (Armstrong-Whitworth FK.8 army co-operation aircraft) on Nov. 29, 1917. His brilliant career culminated in an action on March 27, 1918 for which he was awarded the Victoria Cross. Other distinguished alumni included captains D.R. MacLaren and W.G. Claxton (54 and 31 estimated aerial victories respectively).

A JN-4 attempting a forced landing on

Oshawa’s main street, became entangled

with telephone wires and wound up pinned

to a large storefront where it remained

suspended for several hours.

While the organization was dedicated to training, it made news in ways that heralded future developments. The first airmail in Canada was carried by Capt. Brian Peck from Montreal to Toronto on June 24, 1918, and four additional airmail flights (Toronto to Ottawa and return) were conducted by RAF instructors between Aug. 15 and Sept. 4, 1918; the Ottawa terminus was the Rockcliffe Rifle Range (an area now occupied by the Canada Aviation and Space Museum).

Although the RFC/RAF Canada plan had begun with negligible Canadian direction, it came to include many Canadians at all levels. By November 1918, Canadians commanded the School of Aerial Fighting, two of the three training wings and 12 of the 16 training squadrons. Roughly 60 per cent of all instructors were Canadians.

Historian S.F. Wise has described the RFC/RAF Canada scheme as “the single most powerful influence in bringing the air age to Canada.” The RFC/RAF Canada organization proved the feasibility of year-round flying in this country and even developed special winter flying clothes. Postwar barnstormers quickly gave way to aerial forestry surveyors and frontier bush pilots.

Advertisement