Masumi Mitsui (standing) and comrade Masajiro Shishido pose for a photo in 1916. [Courtesy Nikkei National Museum/2014.10.1.10]

The magical and romantic legend of brave samurai warriors and their heroic adventures and unfaltering personal discipline fuelled Masumi Mitsui his entire life. His father was an officer in the Japanese navy and his grandfather was one of the last authentic samurai to serve the emperor of Japan before the Meiji Restoration in 1868.

From early childhood, Mitsui dreamt of being a noble fighter like his ancestors. His aspiration finally came true, not in Japan, and not even in his new home in Canada, but rather on the gritty battlefields of Europe during the First World War.

Mitsui became a decorated Canadian war hero. He received the Military Medal, the British War Medal and the Victory Medal for his service and bravery in action. He, and 221 other Japanese-Canadian immigrants who served with the Canadian Expeditionary Force, deserve to be remembered for their commitment in defending their adopted homeland.

Born on Oct. 7, 1887, in Tokyo, Mitsui immigrated to Canada in 1908 after he was rejected by the Japanese military. In choosing Canada, he hoped for a new beginning, but instead he encountered hostile discrimination and prejudice. Most Asian immigrants had no rights as Canadian citizens and they typically worked for slave wages, often living in substandard accommodations. This wasn’t his dream, however, and like many other newcomers, a return to the homeland simply wasn’t possible. He persevered.

Mitsui helped form Branch No. 9 of the Canadian Legion of the British Empire Service League (now the Royal Canadian Legion) in 1926.

With the onset of the war in Europe and Canada’s involvement as a member of the British Empire, Masumi and other Japanese Canadians saw an opportunity to demonstrate their loyalty to their new country by joining the CEF. With a few exceptions, however, Asians, weren’t being accepted for duty in B.C.

Undaunted, Mitsui joined the 227-member unsanctioned Canadian Japanese Volunteer Corps led by Yasushi Yamazaki, an organizer in Vancouver.

As war continued to rage on into 1916, and with reinforcements desperately needed, Masumi and his fellow Japanese Canadians discovered they could enlist in Alberta, so they travelled to Calgary at their own expense and were welcomed by the 192nd Canadian Infantry Battalion. It wasn’t long before the Japanese volunteers got the call to fight. The group knew they weren’t just fighting for the Allied forces in Europe; they were also fighting for respect and acceptance at home. For most, it was an opportunity to prove their loyalty.

Mitsui received the Military Medal, the British War Medal and the Victory Medal for his service and bravery in action.

In November 1916, the contingent arrived at the St Martin’s Plain training grounds in the southeast corner of England after field training in Halifax. Mitsui was eventually attached to the 10th Battalion. When they were asked why the Japanese were fighting for Canada, they would say, “We are Canadians, fighting for Canada.”

War was hard. The fighting was difficult, especially for the smaller-statured Japanese soldiers, but they followed orders and fought bravely. Fifty-four of the group were killed in action. They faced the enemy in some of the most infamous encounters of the war, including at Vimy Ridge, where the 10th Battalion used a creeping barrage to gain position, then held the line in the muck and mire for two days. Following that encounter, the JCs, as they came to be called, distinguished themselves in the Battle of Hill 70 and later at Passchendaele.

Mitsui participated in many strategic planning sessions held by the officers thanks to his fluency in English. He translated engagement plans for his less-fluent comrades, which, along with his exemplary leadership in the field, led to his eventual promotion to sergeant.

With the armistice on Nov. 11, 1918, the war ended, but it wasn’t until April of the following year that Masumi and his fellow JCs boarded RMS Carmania to head home.

Japanese-Canadian businessmen who helped sponsor the Japanese Canadian War Memorial in Vancouver’s Stanley Park gather at its unveiling in April 1920. [Roy Kawamoto/Japanese American National Museum]

After the war, Mitsui returned to B.C, determined to find a job that would give him independence and respect. Recalling the small farms he had encountered across Europe and what seemed like an idyllic lifestyle, he used his savings and his war bond and bought a seven-hectare poultry and vegetable farm in Hammond (now Maple Ridge), B.C. He built a house at 1945 Laurier Avenue in nearby Port Coquitlam and became a chicken farmer.

He and his new wife Sugiko had four children and built a successful farming business where he was in charge and didn’t have to endure many of the same challenges other immigrants faced in mills, mines and fisheries.

In search of sustaining the feeling of military camaraderie, Mitsui helped form Branch No. 9 of the Canadian Legion of the British Empire Service League (now the Royal Canadian Legion) in 1926. Made up entirely of local Japanese-Canadian veterans, Mitsui was unanimously elected as its first president.

Aside from a few years of success as a chicken farmer, the best years of Masumi’s life occurred during the most difficult and dangerous time—the Great War. As a soldier, his ethnicity didn’t define who he was as a person. He and his fellow Japanese Canadians were accepted as equals. They fought, lived and died just like everyone else. In return, they expected this new acceptance would follow them back home. But that didn’t happen. In many cases, the animosity and hatred were even worse when they returned. Despite the persistent racism, both before and after the war, Japanese immigrants remained determined to belong as Canadians.

Masumi’s next service to his community was an initiative to erect a memorial to the Japanese Canadians who had fought. With the help of Asian businessmen in Vancouver, a cenotaph with an eternal flame was commissioned and located centrally in Stanley Park in April 1920. It recognized the famous WW I battlefields in Europe and paid tribute to the Japanese-Canadian soldiers who fought on them.

Japanese veterans continued to face the shocking realization that even after risking their lives for their country, they were still treated as second-class citizens in Canada.

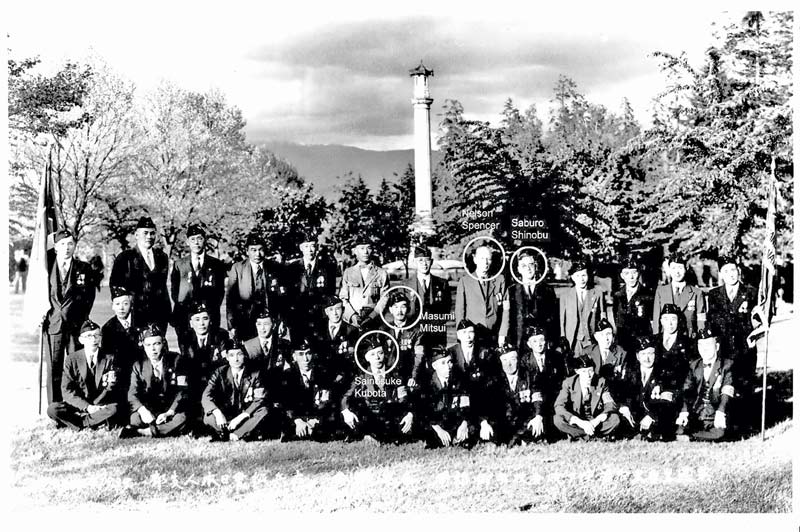

Members of the Canadian Legion Branch 9 pose for a photo at the monument in May 1939. Mitsui in 1987.[Courtesy Russ Crawford]

[Nikkei National Museum/2014.10.1.9]

The situation was exemplified by the fact that most Asian newcomers weren’t allowed to vote in B.C. elections. The fight for the right to vote for all Japanese Canadians became Mitsui’s next battle and, in April 1931, he and a small delegation prevailed in the Victoria legislature and secured, for veterans of Japanese ancestry, the right to vote in B.C. Other Japanese Canadians didn’t get the right until 1949.

Mitsui’s life took another unexpected and decidedly negative turn when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, in December 1941. Instinctively, Mitsui knew what he had to do as another world war loomed. He immediately wanted to enlist but, at 54 years old, his wife and family tried to convince him he was too old to fight. None of their views mattered though, as the Canadian government decided to detain all Japanese Canadians out of a fear they would aid the Japanese war effort—even though many of the younger family members had never even been to Japan.

The internment process was brutal. Japanese Canadians living in B.C. were forcibly sent to camps in the province’s interior under difficult conditions. They were dispossessed of their personal belongings, including homes, fishing boats and vehicles, which were seized and sold well below their value. Their rights were revoked. The families suffered isolation and further discrimination. When they were released, they were left to fend for themselves to rebuild their lives.

Mitsui never stopped feeling a call to duty. During the Second World War, while most Japanese Canadians had been interned in camps, the eternal flame atop the Japanese Canadian War Memorial had been extinguished. After being refurbished by the Japanese-Canadian community, the memorial’s flame was relit on Aug. 2, 1985. Mitsui was a guest of honour at the ceremony, one of two surviving Japanese-Canadian soldiers from the First World War.

Masumi Mitsui embodied the spirit of a modern-day samurai. While he was certainly a wartime hero, he was also a champion for change. He was relentless in his fight for equality for Japanese Canadians and he dedicated himself to efforts of remembrance for his comrades.

Read more about the life of Masumi Mitsui in the biography Canadian Samurai: One Man’s Battle for Acceptance by Russ Crawford.

Advertisement