Beatrice Harrison plays her cello in her garden at Foyle Riding.

[Science Museum/Science and Society Picture Library]

While all those tapes were made between 1939 and 1945, providing listeners with spellbinding sound, few—if any—bore the poignancy of a nightingale’s song set to the ominous, Beethovian rumble of 197 Allied warplanes passing overhead.

Subtle as it is, the recording, made in an English country garden by the BBC on May 19, 1942, is an eloquent reflection of the dichotomy between war and peace, the distant hum of airplane engines gradually turning the nightingale’s light-hearted evening sonata into full-blown symphony of appropriately Germanic proportions.

“Appropriately” because the 105 Wellington, 31 Stirling, 29 Halifax, 15 Hampden, 13 Lancaster and four Manchester bombers were headed to Germany—the industrial centre of Mannheim, to be precise, home of the Mannheim Motorenwerke and naval armaments factories.

Mannheim would be hit many times over the course of the war, its city centre destroyed, and thousands of residents killed. After the German bombing of Coventry, England, in 1940, an arguably retaliatory raid on Mannheim by 134 aircraft marked the largest Allied mission to date, and the first to abandon the concept of strategic bombing in favour of indiscriminate carpet bombing.

The nightingale is threatened by climate change and habitat loss.

[Wikimedia]

The voice of the bird followed me…It seemed a miracle.”

By contrast, the garden at Foyle Riding, near Oxted in Surrey, 41 minutes south of London’s Victoria Station, was the picture of refined peace and serenity.

It had been owned by British cellist Beatrice Harrison who, late one warm summer night in the early-1920s, discovered the nightingales appeared to sing along as she practised with her windows open.

“I began the ‘Chant Hindu’ by Rimsky-Korsakov and, after playing for some time, I stopped,” Harrison recalled years later. “Suddenly a glorious note echoed the notes of the cello. I then trilled up and down the instrument, up to the top and down again…The voice of the bird followed me…It seemed a miracle.”

Harrison was well-known. She had given first performances of several important English works, notably Frederick Delius’s, and made the first or signature recordings of others including, in 1920, the first recording of Sir Edward William Elgar’s cello concerto with the composer conducting.

Enchanted by the nightingales, Harrison contacted BBC chair John Reith, suggesting he broadcast her avian collaboration. Reith was initially dubious but, given Harrison’s reputation, he allowed himself to be convinced.

And so, on May 18, 1924, a tradition was born. And in historic fashion: What amounted to an experiment with BBC engineers Peter Eckersley and A.G.D. West using the new Marconi-Sykes magnetophone was long touted as one of the first live-to-radio broadcasts originating outdoors ever made.

The sensitive Marconi-Sykes had initially confused engineers until they realized the sounds they’d been hearing were insects and birds. The device opened a new world of possibilities in radio.

From Foyle Riding, the Marconi-Sykes’ amplified signal travelled by telephone line to the broadcast facilities at the central BBC station in London. It’s estimated a million people listened to the first nightingale broadcast at midnight on that May 18. It created such a phenomenon the experiment was repeated a month later—or so the story went for almost 100 years.

Thousands of visitors had begun descending on the estate during nightingale season.

In fact, the first broadcast was faked using a bird impressionist, the BBC acknowledged in 2022.

The Guardian newspaper reported that the nightingales may have been scared off by the crew tromping around the garden with heavy recording equipment. A back-up plan was already in place—an understudy, believed to have been Maude Gould, a whistler, or “siffleur,” known as Madame Saberon on variety bills.

Before the second annual nightingale broadcast in 1925, Reith wrote that the birds of Foyle Riding had swept Britain with “a wave of something closely akin to emotionalism…a glamour of romance has flashed across the prosaic round of many a life.”

Thousands of visitors had begun descending on the estate during nightingale season.

“Buses were chartered, guests entertained, and charity visits arranged,” reports the website publicaddress.net. “The Harrisons received over 50,000 fan letters.”

Professor Tim Birkhead, a leading bird expert, told the Guardian: “When Harrison repeated the performance in subsequent years, the BBC were a bit more careful about trampling through a garden and it was a real nightingale. That was the essence of it, that they’d scared it away.”

HMV made a recording on May 3, 1927, featuring Harrison playing the balad “Danny Boy,” accompanied by actual nightingales. The 1942 recording would be featured 33 years later on the Manfred Mann’s Earth Band album “Nightingales and Bombers.”

The BBC maintained the live-broadcast tradition each year from Foyle Riding, and continued to record the birds solo after Harrison left the 16th century English country estate in 1936. That is, until the night of May 19th, 1942, when, with the bombers headed eastward, a technician pulled the plug just as the broadcast was going to air.

Having fought off the Nazi threat to hearth and home and endured The Blitz, Britain was by 1942 a staging ground for air raids into Germany and occupied Europe. In what would become a stalwart of the bombing offensive, the Avro Lancaster had just been introduced. The countryside was teeming with troops and air crews of multiple nationalities preparing for The Great Crusade that was to come in two years. Spies were everywhere, or so it seemed.

So to broadcast live what was obviously a large formation of warplanes heading somewhere east would have been an inexcusable gaffe, and likely worse.

Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris, commander in chief of Royal Air Force Bomber Command, seated at his desk at Bomber Command HQ, High Wycombe, England.

[RAF/Wikimedia]

“It is apparent from the night photographs and from the reports of crews, that almost the whole effort of the raid was wasted in bombing large fires in the local forests, and possibly decoy fires,” Harris wrote at the time. “Nevertheless, in spite of the now incontrovertible evidence that this is what in fact occurred, the reports of the crews on their return from the raid were most definite in very many cases that they had reached the town and bombed it. Many reports spoke of recognising features of the town and the river, and of fires being definitely located in the town.

“The cause of this failure is beyond doubt to be found in the easy manner in which crews are misled by decoy fires or by fires in the wrong place. If any fire is distinctive in its nature and comparatively easy to recognise it is a forest fire. The results on this occasion show that few if any of the crews took the trouble, or alternatively came low enough, to make certain of the nature of the fires.”

If such failures continued, crews were to be told, they would be sent back to Mannheim repeatedly until the job was done properly.

Given to extreme statements, the controversial father of carpet bombing and architect of the infamous Dresden fire-bombing told his group commanders that if they did not exercise closer supervision, the “large number of influential people who…are quite convinced that the Bomber force is not justified…will have their way in destroying it, and consequently possibly the RAF also as a separate service.”

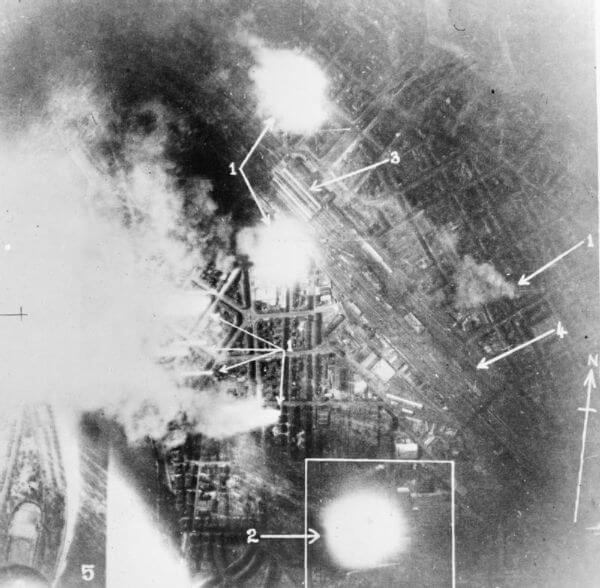

A night raid on Mannheim.

[IWM]

Based at RAF Alconbury north of London, Mathieson, 23, co-piloted the 156 Squadron Wellington, tail No. X3671. The plane and its six-member crew never made their target. They were shot down at 11:51 p.m. by Oberleutnant Hubert Rauh, a Bf 110 nightfighter pilot, near the French village of Hargnies in the Ardennes close to the Franco-Belgian frontier. No one survived the crash.

The crew was typical of Bomber Command’s patchwork makeup. Besides the Canadian No. 2, the pilot, 26-year-old Acting Squadron Leader Thomas Campbell McGillivary, a recipient of the Distinguished Flying Cross, was from New Zealand.

The others were all Royal Air Force Volunteer Reservists from England:

- Pilot Officer Kenneth Vincent Whelan was the wireless operator;

- Pilot Officer Denis Hellyer, 25, whose parents lived in Surrey not far from Foyle Riding, was the observer;

- Sergeant Charles Corbett Stevens, 21, and Pilot Officer Edward Francis Valentine, 20, were the gunners.

They are buried together in the Hargnies Communal Cemetery.

The Bomber Command report on the raid described a long delay before the attack developed, with aircraft at higher altitudes than usual, passing to and fro, searching for the target. Ultimately, it said, bombs about equivalent to no more than 10 aircraft loads fell in the city.

A concentrated group of about 600 incendiaries in the harbour area on the Rhine burnt out four small industrial concerns—a blanket factory, a mineral water factory, a chemical wholesaler and a timber merchant. Only light damage was reported elsewhere.

Mathieson is buried with his crewmates in a common grave at Hargnies in northern France. [Johan Pauwels]

“The loss of bird life is immense: 600 million birds fewer in Europe since in 1980.”

Advertisement