![Canadian soldiers advance on the Gothic Line, August 1944. [PHOTO: NATIONAL DEFENCE, LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA—PA177533]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/12/coppleadjf09.jpg)

The German army’s Apennine defences, known to the Allies as the Gothic Line, stretched across the Italian peninsula. The strongest sections were in the American sector guarding the direct approaches to Bologna, but the two-month delay between the capture of Rome and the beginning of Operation Olive, 8th Army’s offensive, allowed time for German engineers and Italian labourers to enhance the natural obstacles of ridge lines and rivers with prepared positions.

The work was concentrated on what the Germans called Green Line One, which on the Adriatic front was located on the high ground north of the Foglia River. It was here that most of “the 2,375 machine-gun posts, 479 anti-tank gun, mortar and assault-gun positions, 3,604 dugouts and shelters, 16,006 rifleman positions, 72,517 teller anti-tank mines and 23,172 anti-personnel mines” were placed. As the Canadian official historian G.W.L. Nicholson has noted, this impressive effort was supplemented by “117,370 metres of wire obstacles and 8,944 metres of anti-tank ditch.” Four Panther tank turrets and 18 smaller gun turrets had been added by late August.

At 8th Army headquarters, intelligence officers studying air photographs drew the conclusion that Green Line One was the Gothic Line rather than the main position of a deeper defensive zone. This mistake contributed to the optimism of 8th Army planners who seemed to believe, against all previous experience, that armoured divisions would be able to advance quickly once the Foglia defences were breached.

Lieutenant-General E.L.M. Burns and his divisional commanders, Chris Vokes and Bert Hoffmeister worked within a plan devised by 8th Army. But once the operation began Canadian commanders at all levels would have to adapt, innovate and lead. Lieutenant-General Oliver Leese had outlined two possibilities, a set-piece attack after a brief pause, or an attempt to “gate crash” the defences after two days of softening up with medium bombers. Leese opted for speed and Burns ordered Hoffmeister’s 5th Armoured Division to take over the left flank of the narrow Canadian corridor so that both 5th and 1st divisions could control their own bridgeheads.

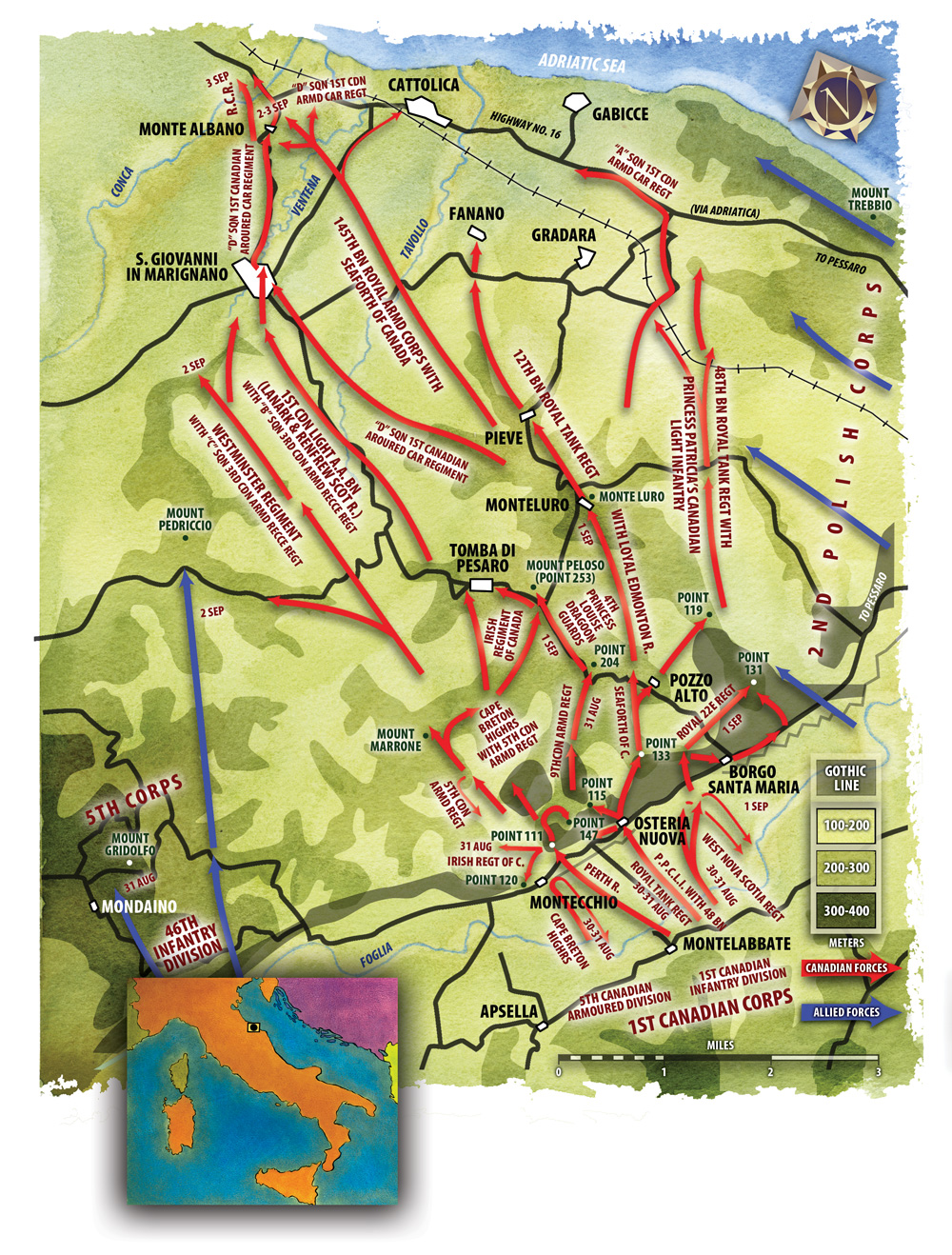

Click To View Map.

On the 5th Div. front, Hoffmeister gave Brigadier Ian Johnston freedom to plan the attack using his own 11th Infantry Brigade with the 8th New Brunswick Hussars and Princess Louise Dragoon Guards under command. The PLDG had been converted from a reconnaissance regiment to infantry, one of three “new” battalions formed to create an additional infantry brigade for the armoured division.

Johnston was faced with a difficult problem. His carefully prepared Appreciation document, which outlined a plan of operations, was based on a survey of the ground on either side of the village of Montecchio. If you visit the Foglia and examine the terrain from the heights south of the river, it becomes evident that the village sits between two hills. During the war these hills were known as points 120 and 129.

With minefields between the river and the hills, the enemy had excellent fields of fire that would create a dangerous killing ground. Needless to say, both hills had to be secured prior to an advance.

Johnston decided on a night attack with ample artillery support.

Many years later Hoffmeister recalled his first view of the Montecchio feature. It was “a real fortress in itself, a great rocky thing, with good approaches (for the enemy) from the back…we could pick out the odd concrete gun emplacement and we could see the barbed wire, and we saw minefields, but there was no life around the place at all.” Hoffmeister thought there “was something wrong” and suggested that Johnston do extra patrolling, but he did not protest Leese’s decision to rush the defences.

The decision to gate crash meant that the attack actually began in broad daylight without waiting for all units to reach the start line. Martha Gelhorn, who in 1944 was a well-known, respected war correspondent, watched the battle “from a hill opposite, sitting in a batch of thistles and staring through binoculars.” The battlefield included the Foglia and the Via Emilia, a road paralleling the river, where she noted “the Germans dynamited every village into shapeless brick rubble so that they would have clear lines of fire. In front of the flattened villages they dug their long ditch to trap tanks. In front of the tank trap they cut all the trees. Among the felled trees and in the gravel bed and low water of the Foglia they laid down barbed wire and sowed their never-ending mines, the crude little wooden boxes, the small rusty tin cans, the flat metal pancakes which are the simplest and deadliest weapons in Italy.” All of this in front of the Green Line fortifications in the many hills beyond the deadly valley.

The Cape Breton Highlanders advancing on the brigade, divisional and corps left flank found a route through the minefield and reached the slopes of Pt. 120, their objective before the enemy opened fire with machine-guns positioned to cover every approach. The Germans then counterattacked the Canadians, forcing the battalion to withdraw and wait for darkness. The Perth Regiment on the brigade’s right flank was stopped by mortar and machine-gun fire which devastated the lead platoon. Again common sense, prevailed and a further attack was postponed until dark when machine-guns—firing on fixed lines at set intervals—could be avoided through a series of quick rushes. The Perth Regt. reached a position known as Pt. 111 and seized the hill in a mad charge led by Captain Sammy Ridge. The Cape Breton Highlanders, facing “the anchored fortress of Montecchio” were less fortunate and despite supporting fire from tanks of the New Brunswick Hussars artillery and much bravery, Pt. 120 would not be taken by direct attack.

A similar pattern developed on the 1st Div. front. The West Nova Scotia Regt., who like the Cape Breton Highlanders, advanced in daylight on the outside flank, found their objective, Borgo Santa Maria, protected by a wide belt of wooden-encased Schü-mines, each with an explosive charge large enough to severely damage a man’s leg. The much vaunted bombing program, 1,600 tons of bombs dropped in two days over 8th Army’s front, could not possibly destroy such extensive minefields and so the West Novas were trapped in a killing zone under continuous mortar fire.

The regimental history describes the scene as “the Ortona affair all over again” with “nothing to do but dig in as quickly as possible.” Only the foolish optimism of generals could account for a daylight advance over such ground and “for the rest of the long summer evening the West Novas hung on, maintaining an energetic, but hopeless firefight with the enemy on the slopes—all that prevented a massacre was the fact that the Germans ran out of mortar ammunition. This limited the West Nova casualties to 90 men.

As the West Novas withdrew, the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry was ordered to cross the river and seize the village of Osteria Nuova. They relied on full darkness to avoid mortar and machine-gun fire, but the band of Schü-mines and barbed wire were a major obstacle.

Major Colin McDougall, who was later to write the powerful Italian Campaign novel, Execution, commanded the lead company. “We moved off in single file,” he recalled. “11 platoon leading. We had to go down a path which like the area on both sides, was heavily mined. After we got through that with some casualties, we crossed the anti-tank ditch, also mined, which runs parallel with the river.…”

By first light, the company reached a pile of rubble that was once a village. It then went into action to clear the area assisted by the advance of 5th Div. armour on their left flank. A second breach in the Green Line was thus made secure. It was now up to the reserve battalions to exploit these tactical gains. Johnston was quick to commit the Irish Regt. with a squadron of 8th Hussars tanks. His new plan sent the battle group through the Perth Regt. to attack the Montecchio from the rear as well as both flanks. Working as mobile artillery, the tanks “threw a creeping barrage ahead of the Irish firing over open sights…the Irish were on the Germans with bayonets before they could stand up to fight.…” By the evening of Aug. 31, Montecchio was secure.

On the 1st Div. front, the Royal 22nd Regt. was able to exploit the Patricia’s initial success clearing the last enemy outposts in Borgo Santa Maria before waging a day-long battle for another hill, Pt. 131, situated immediately beyond the village. The Seaforths fought a similarly bitter struggle for Pozzo Alto and managed to secure the ruined hamlet on the third attempt. Somehow, Lieutenant-Colonel S.W. Thomson’s men still found the strength to continue the advance to Pt. 119, situated almost a mile further to the northeast.

Hoffmeister and Johnston decided to exploit the capture of Montecchio. They sent the British Columbia Dragoons, with the Perth Regt. under command, to capture Pt. 204, an extension of the Tomba di Pesaro ridge line where the enemy was reforming. There was not enough time for a proper orders group and Lt.-Col. Fred Vokes used his regimental radio net to brief squadron and troop commanders as they raced to the forming up place to meet the Perth Regt. The designated map reference, code-named Erindale, turned out to be held by determined German soldiers who destroyed several A Sqdn. tanks before they were overcome. Erindale—Death Valley to the British Columbia Dragoons—was still under fire and there was no sign of the Perth Regt. which was pinned down by observed artillery fire, “the worst they had ever experienced.” Vokes decided to send C Sqdn. to capture Pt. 204 “and hold it until relieved.”

As C Sqdn. advanced through Death Valley towards Pt. 204, Major G.E. Eastman ordered A Sqdn. to abandon the forming up place and follow them to the high ground. After knocking out an 88-mm gun they joined their comrades in reaching Pt. 204, but only after skirting one of the formidable Panther turrets set atop a concrete bunker that housed the crew. Apparently artillery fire or lack of will to fight kept the German soldiers safely underground. This allowed the British Columbia Dragoons to dismount and capture the position without firing a shot.

Today’s traveller can pause and visit Pt. 204 where a small park, monument, gun turret and explanatory plaques offer an account of the battle for the Gothic Line. The view towards Tavulla—the modern name for Tomba di Pesaro—and the surrounding countryside is breathtaking, and the vital nature of the position is quite evident. The calm security of the park is in sharp contrast to the events it commemorates. The British Columbia Dragoons had broken through a portion of the Green Line, but by late afternoon on Aug. 31 they were under continuous fire and suffered heavy casualties, including their commanding officer, Fred Vokes. The BCDs held until relief in the form of the Perth Regt. and a Strathcona Horse squadron fought their way to Pt. 204.

The action carried out by the BCDs has been viewed differently by historians. Royal Military College of Canada historian Doug Delaney has condemned the “bad decisions made by the Dragoon Commanding Officer” who “had grown impatient waiting for the Perths to link up with his tanks and decided to go without his infantry support.” Delaney is also critical of “Vokes’ failure to have artillery fire neutralize the German anti-tank guns on the ridge.…” Lee Windsor, the University of New Brunswick historian, sees the action very differently, arguing that the seizure of Pt. 204, and the long battle to hold it, lured the Germans out of their dugouts to counter-attack the Dragoons. This allowed Canadian artillery to crush enemy counterattacks. Such a “bite and hold” approach had proven to be the most effective method available to the Allies, though most commanders adopted it only after their more ambitious plans had been frustrated.

Gelhorn, who watched these events unfold, wrote that “it was the Canadians who broke this line by finding a soft place and going through…. It makes me ashamed to write that sentence because there is no soft place where there are mines, and no soft place where there are the hideous long 88-mm guns, and if you have seen one tank burn on a hillside you will never believe that anything is soft again. But relatively speaking this spot was soft or, at any rate, the Canadians made it soft.”

While trying to make sense of the battle, Gelhorn followed the Canadians across the river. She described it as a “jigsaw puzzle of fighting men, bewildered, terrified civilians, noise, smells, jokes, pain, fear, unfinished conversations and high explosives.” At a regimental aid post she met the medical officer, a captain who told her the story of a Canadian padre who helped the stretcher-bearer when things got really bad in the minefields. “The padre lost both legs and though they rushed him out he died at the first hospital.” Gelhorn, who had heard the news of the German collapse in Normandy, shared the general view that the war would soon be over, so she found the Foglia battlefield unbearably sad. “It is,” she wrote, “awful to die at the end of the summer…when you are young and have fought a long time…you know the end of all this tragic dying is so near.”

Unfortunately, Hitler and the German commanders in Italy were determined to continue the war and prevent a breakthrough into the Po Valley. The 26 Panzer Div., the first reinforcements, was in action against the Canadians on Aug. 31, and 29 Panzer Grenadier Div. was on its way to the Adriatic sector. German determination to prevent a breakthrough in Italy has always puzzled historians as has the Allied insistence on pressing a costly campaign in a secondary theatre. Lee Windsor argues convincingly that by 1944 the industries of northern Italy were an important part of the German war effort justifying the relatively modest reinforcements sent to Italy. It is less clear why the Allied commanders were determined to turn a holding action designed to keep German divisions away from France into an attritional battle. All the Allied armies were desperately short of trained infantry in the second half of 1944, and in Northwest Europe, Bernard Montgomery was preparing to disband yet another infantry division to provide replacements for his seven remaining infantry divisions. Leese was well aware it would be difficult to make up losses from the reinforcement pool in the Mediterranean, but on the evening of Aug. 31, 1944, he was convinced the Canadians were on the verge of a breakthrough and he was determined to press the attack.

Email the writer at: writer@legionmagazine.com

Email a letter to the editor at: letters@legionmagazine.com

Advertisement