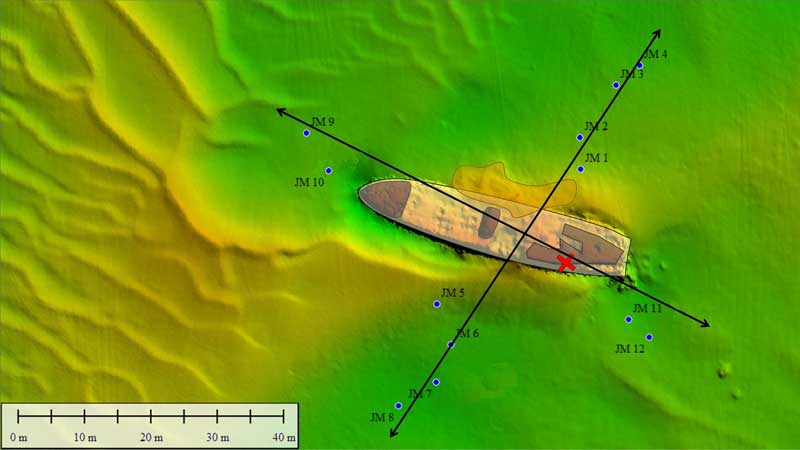

The German vorpostenboot, or patrol boat, V-1302, formerly known as the John Mahn, sits at the bottom of the North Sea off the Belgium coast. [Van Landuyt et al/Frontiers in Marine Science]

The vessel formerly known as the John Mahn out of Hamburg was one of six auxiliary ships from the Kriegsmarine’s 13th flotilla that took up fixed positions during Operation Cerberus, more commonly known as The Channel Dash.

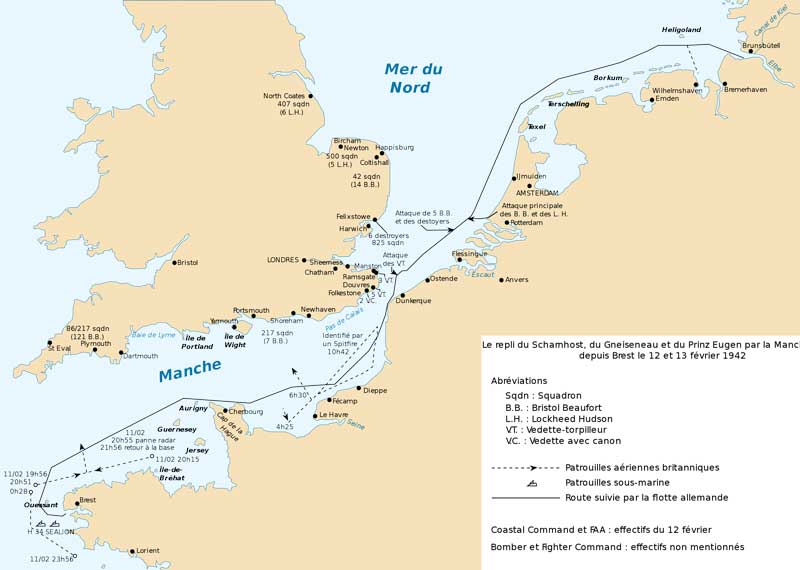

In what amounted to a convoy mission, some 200 vessels set out to escort the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen and the battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau from Brittany in France through the English Channel to German ports.

The German vorpostenboot V-1605 Mosel comes under a fatal hail of bullets from Beaufighter aircraft of 404 Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force, as it escorts a Norwegian freighter off Lillesand, Norway, on Oct. 15, 1944.

[ HQ Coastal Command/Wikimedia]

The convoy’s anti-aircraft guns opened up about 2:50 p.m. The first British fighters and bombers were engaged within 10 minutes.

At 3:25 p.m., as four other vorpostenboote raised their anchors and moved closer to V-1302, the group was attacked by two British Lockheed Hudson bombers along with several Supermarine Spitfire and Hawker Hurricane fighters.

V-1302 and its compatriots put up a heckuva fight. At 3:53 p.m., the former fishing vessel was surprised by a group of six bombers (some reports say they were Hurricanes). V-1302 and the Freiburg scored multiple hits on one. As the plane lost altitude, it clipped the former’s masthead and tumbled into the sea.

A multibeam sonar image of the wreck of V-1302 shows the sites where researchers took sediment samples.

[Van Landuyt et al/Frontiers in Marine Science]

V-1302 began to go down by the stern, its bow machine-gun crew continuing to fire and registering several hits before the 48-metre vessel heeled over and sank with her reserves of coal and munitions a half-minute later.

Twenty-seven of V-1302’s crew were rescued by vorpostenboote and ships of the 2nd Minensuch-Flottille; 11 others disappeared and were presumed dead.

V-1302—the John Mahn—was the only German ship sunk during The Channel Dash, though several other vessels were damaged by mines and air strikes, including Scharnhorst and Gneisenau.

“Shipwrecks on the seafloor worldwide contain hazardous substances such as explosives and petroleum products that, if released, may harm the marine environment.”

Today the wreck lies slightly askew 35 metres down on the seabed off the Belgian coast, largely intact. A gaping hole on the port side is the first clue as to how it got there. Divers have found a lethal store of 88mm shells, 20mm cartridges and at least six depth charges still aboard.

A map of the February 1942 Channel Dash shows the German convoy’s route from Brest to the mouth of the Elbe River.

[Wikimedia]

Chemicals and corroding microbes found in samples taken from the hull of the ship are affecting the “surrounding sediment chemistry and microbial ecology,” the researchers wrote.

“The John Mahn shipwreck, even after almost 80 years on the seafloor, seems to still leach micropollutants into the sediment, both from the coal bunker (aromatic compound content) as well as munition (still) present on the wreck (TNT content) and the wreck itself (heavy metals).”

The results, notes the study, point to the potential long-term environmental impacts of shipwrecks in the North Sea and around the world.

“The general public is often quite interested in shipwrecks because of their historical value, but the potential environmental impact of these wrecks is often overlooked,” said Josefien Van Landuyt, a study co-author and PhD candidate investigating marine biodegradation out of Ghent University in Belgium.

“Shipwrecks on the seafloor worldwide contain hazardous substances such as explosives and petroleum products that, if released, may harm the marine environment,” said the document. “In contrast to artificial reefs (i.e., intentionally sunk vessels and structures), wartime shipwrecks were sunk without being stripped of hazardous substances, often having reserves of crude oil or other petroleum derivatives and unexploded munitions still on board.

“While wrecks are often considered biodiversity hotspots, the overall environmental impact on the seafloor of historic shipwrecks from the World Wars has only recently sparked interest.”

The findings suggest that the impact of shipwrecks on marine environments is not fully understood, nor appreciated.

In the V-1302 samples with the highest concentrations of pollutants, Van Landuyt and her colleagues found microbes known to degrade chemicals. They’re called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and they occur naturally in coal, crude oil and gasoline.

Those findings suggest that the shipwreck itself, as well as the pollutants leaking from it, “drive at least part of the bacterial community structure in the surrounding sediment,” the researchers wrote.

The pollutants included heavy metals, nickel and copper among them.

“The highest metal and metalloid concentrations were found in the sample closest to the coal bunker, with specifically a high nickel, copper, and arsenic content.”

The findings suggest that the impact of shipwrecks on marine environments is not fully understood, nor appreciated, especially in cases where the precise locations of sunken ships laden with munitions and petroleum are not even known.

“Although we don’t see these old shipwrecks, and many of us don’t know where they are, they can still be polluting our marine ecosystem,” Van Landuyt said in a statement. “In fact, their advancing age might increase the environmental risk due to corrosion, which is opening up previously enclosed spaces. As such, their environmental impact is still evolving.”

Vorpostenboote (patrol boats) were the workhorses in the coastal operations of the Kriegsmarine. Used for patrol or picket duty, escort or submarine hunting, these small vessels were used in virtually every coastal area where the German navy operated.

[Kriegsmarine]

“In addition,” they wrote, “up to 1.6 million tonnes of ammunition of all types (both attached to and separate from ships) were sunk or dumped in the Northern seas of Europe after both World Wars.

“The few studies performed on the subject suggest explosive compounds such as trinitrotoluene (TNT) and its derivatives, as well as chemical warfare agents, can have toxic effects on aquatic wildlife.

“However, the influence of these compounds on an ecological level remains unclear.”

V-1302 research is part of the North Sea Wrecks project, which is studying seabeds around shipwrecks off the Belgian coast.

Said Van Landuyt: “People often forget that below the sea surface, we—humans—have already made quite an impact on the local animals, microbes and plants living there and are still making an impact, leaching chemicals, fossil fuels, heavy metals from sometimes century-old wrecks we don’t even remember are there.”

Advertisement