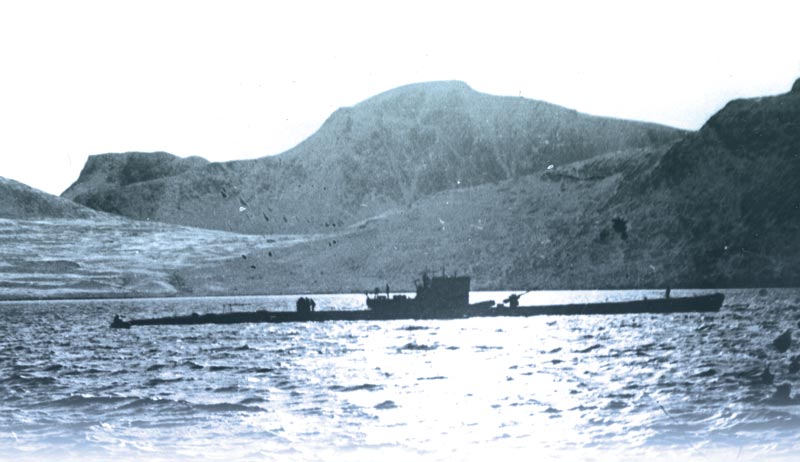

U-537 at anchor in Martin Bay, Nfld., on Oct. 22, 1943. Its crew set up a secret remote weather station there [Wikimedia/German Federal Archives; CWM/19820219-001]

The Canadians wouldn’t believe me,” retired German engineer Franz Selinger told the Associated Press in 1981. Selinger was, after all, seemingly purporting a quasi-kooky idea. It was absurd, hare-brained and a little too close for comfort: proof the Nazis had operated in Canada during the Second World War.

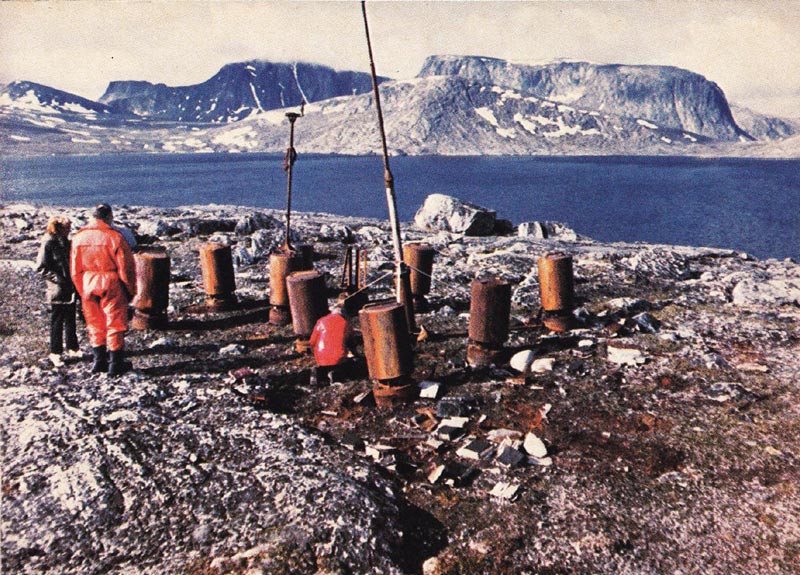

During the Torngat Archaeological Project in 1977, geomorphologist Peter Johnson had dismissed the idea when he spotted canisters and an antenna in northern Labrador. Giving it no more notice than a Canadian proto-weather station deserves, Johnson called the find “Martin Bay 7” after the nearby geographic feature, issued it an identification number and moved on.

Little did Johnson know, however, that the station already had a name: Wetter-Funkgerät Land-26—the only Second World War Nazi installation on North American soil. But at the time, no one on the continent knew about it.

During the Second World War, the German Kriegsmarine had been challenged by inaccurate weather forecasts. With the Allies often holding northern and western positions, and storms usually known to migrate from west to east, north to south, the unreliable predictions the Germans had would often compromise their operations.

To remedy this, German company Siemens-Schuckertwerke created a new type of automatic weather observatory. Code-named Kröte, or “toad,” the first couple of installations in Norway were dismantled either by people or all-too-curious bears. As Germany’s need to maintain a blockade in the North Atlantic remained, the Germans were itching for an ideal forecasting location. Soon they considered remote Labrador.

[German Admiral Karl] Dönitz evidently expected to be making good use of the information beamed from Labrador.”

—Alec Douglas, official historian of the Canadian Armed Forces, 1973-1994

U-537 set sail from Norway with the new tech on Sept. 30, 1943. When its crew, accompanied by meteorologist Kurt Sommermeyer, made landfall, black-capped sailors lugged the 100-kilogram canisters and 10-metre antennae in the fog to the top of a nearby hill.

The installation, today referred to as Weather Station Kurt after its senior technician, was born. Unfortunately for the Germans, the station stopped working after only two weeks, so it had little impact on the war.

which was discovered by Canadian researchers in 1981.[Wikimedia]

Meanwhile, while scavenging for primary sources for a book he was writing in the early 1980s, Selinger obtained a mighty find: a U-537 logbook accompanied by photographs. The story of the weather station was there. And it wasn’t like the idea of its existence had been groundless. Inuit seal hunters had told the Allies of U-boat sightings during the war and, given the importance of forecast accuracy at the time—the conflict was known as the North Atlantic weather war—you would have thought ears would have perked up.

Selinger teamed up with Alec Douglas, then the official historian for the Defence Department, to locate the station. They travelled to northern Labrador in 1981 to confirm the station’s existence. They found it easily, though the site had clearly been disturbed. The canisters had been opened, electronic parts had been systematically dismantled and wires connecting the works had been cut—though by whom remains a mystery.

A series of logistical battles followed as Douglas fought with many institutions to find Kurt a new home, while also giving it the recognition it deserved. Today, it can be viewed at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa.

“To my mind, it is important,” said Douglas, “because [it’s] not in the routine interests of Canadian historians.”

BY THE NUMBERS

10

Height in metres

of Weather Station Kurt’s antenna

150

Watts of the station’s transmitter

100

Weight in kilograms

(220 pounds) of each

of 10 canisters that were part of the system

14

Number of similar stations deployed in other parts of the Arctic and subarctic

Advertisement