A Royal Canadian Navy officer questions Japanese-Canadian fishermen while confiscating their boat. [Wikimedia]

“I do not see that there is much to gain by trying to apologize for acts of our great grandfathers and their great-grandfathers,” Trudeau told McDonald in the House of Commons. “I do not believe in attempting to rewrite history in this way.”

Revisiting historic actions in such a fashion was a new concept, so expressing remorse for the internment of Japanese Canadian was a big deal. It would set a precedent for others who had historically encountered similar treatment by the government.

“I am not quite sure where we could stop the compensating,” said Trudeau. “I know that we would have to go back a great length of time in history and look at all of the injustices which have occurred, perhaps beginning with the deportations of the Acadians and going on to the treatment of the Chinese Canadians in the late 19th century.”

Opposition leader Brian Mulroney subsequently “entered a heated exchange with Trudeau and shouted that a Conservative government would surely compensate Japanese Canadians,” wrote activist Roy Ito in a history of the debate published on the National Association of Japanese Canadian’s website.

Indeed, four years later, on Sept. 22, 1988, Prime Minister Mulroney formally apologized to Japanese Canadians for wartime internment and instituted a $300-million compensation package.

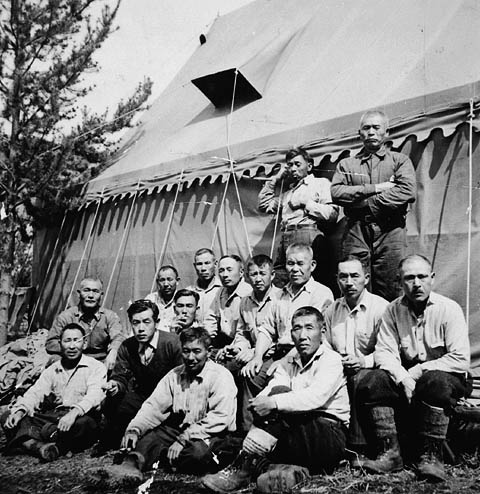

A group of interned men pause during work building the Yellowhead Highway. [Wikimedia]

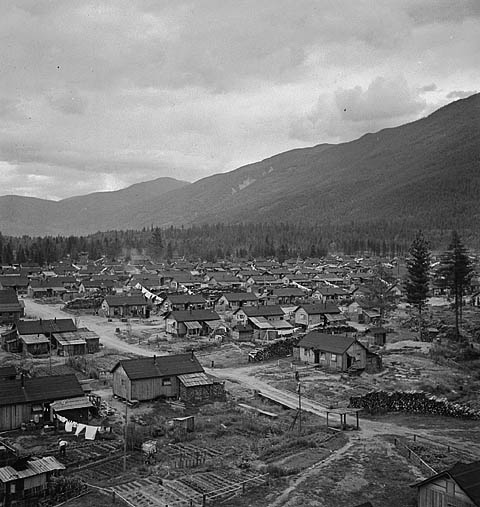

Though the order applied to “any and all persons,” it was specifically used to intern some 21,000 Japanese Canadians living in British Columbia, fearing they were loyal to Japan and could attack Canada from within. More than 90 per cent of Japanese Canadians were detained and their possessions sold to cover the costs of their forced relocation. While men were sent to work on roads, railways and farms, women, children and the elderly were moved to separate camps, with everyone experiencing poor living conditions and treatment.

“The military threat cited to justify the detention of Japanese Canadians never existed outside the anxious imaginations of some British Columbians,” James H. Marsh wrote in a Canadian Encyclopedia editorial. “Not a single Japanese Canadian was charged with any wrongdoing.”

The Lemon Creek Internment Camp in B.C.’s Slocan Valley in June 1944.[Wikimedia]

“Some 11,000 Japanese Canadians, victims of persecution, are still alive today,” The Toronto Star stated. “It’s not a matter of apologizing to the dead…but of meeting the grievance of living Canadians.”

The NAJC finally met with federal government representatives in Montreal on Aug. 24, 1988. After 17 hours of discussions, the long-awaited agreement was struck. The compensation package included $21,000 to each internment survivor, $12 million for a Japanese community fund and $24 million for the creation of a race relations foundation.

Mulroney’s apology in the House of Commons received a standing ovation. And it set a precedent for future similar acknowledgements.

Some injustices may have been before Confederation and the formation of modern “Canada.”

Advertisement