Patrolling over the Indian Ocean, pilot Leonard Birchall and his aircrew spotted an approaching Japanese fleet

It had been a long, uneventful flight. After 12 hours of scanning the vast Indian Ocean without luck, the pilot of the Royal Canadian Air Force Catalina flying boat decided to return to base. Suddenly, the navigator cried out; he had seen something on the horizon. The pilot banked and headed toward the sighting.

It was a Japanese raiding fleet heading for Ceylon (Sri Lanka). As the radio operator sent a warning message to alert the island, Japanese fighters swarmed the flying boat. Cannon shells tore through the aircraft and set it on fire, forcing the pilot to crash land.

Six of the nine crewmen survived and were picked up by a Japanese ship. Their next three and a half years were spent in the horrors of prisoner of war camps.

But had their warning message gotten through?

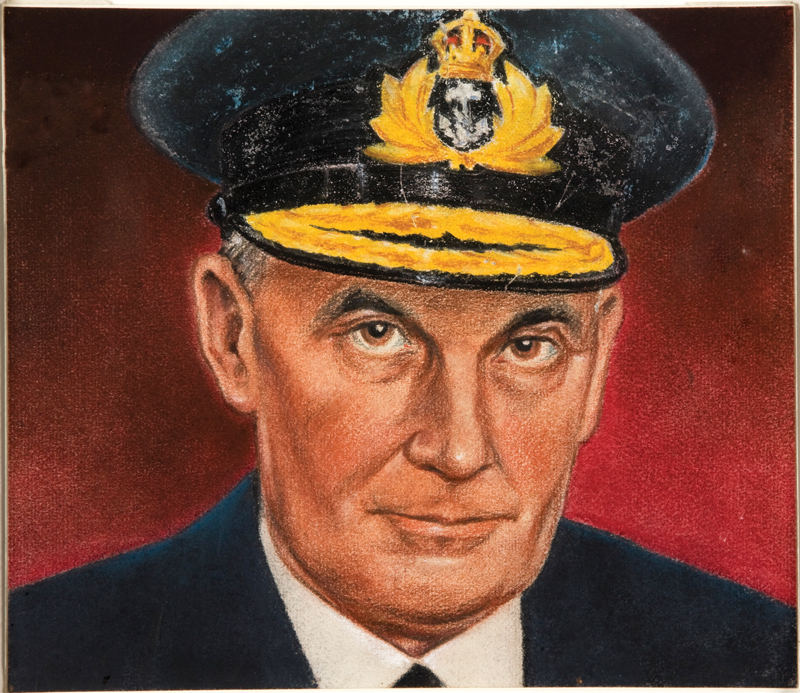

Known as the “Saviour of Ceylon,” Leonard Birchall (opposite) commanded 413 Squadron, RCAF, and its four Consolidated Catalina flying boats (inset and above) at its base in Koggala on Ceylon’s south coast. Birchall piloted the Catalina, ultimately shot down, that warned of an incoming Japanese fleet. [Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame; LAC/400929]

At the end of February 1942, No. 413 Squadron, RCAF, was told it was being sent from Scotland to Ceylon. The slow speed and immense endurance of the unit’s Consolidated Catalina flying boats allowed them to stay airborne for 24 hours. The crew consisted of two pilots, flight engineer, navigator, four to six wireless operators/air gunners and maintenance personnel.

The Catalina’s armament included four to six depth charges on wing mounts (enough for one attack) and four .303 machine guns: one in the nose, one in each of two side “blisters” and a fixed one in the tail. Detection of enemy vessels depended mainly on the time-proven “Mark I eyeball.”

On March 28, the first aircraft reached the squadron’s base at Koggala on Ceylon’s south coast, where a large lake served as a runway and base for the flying boats. The military situation was tense.

British forces were in full retreat in Burma. Attacks on India, Ceylon or the British Eastern Fleet could be next. That was exactly what the Japanese were planning: they had dispatched a large fleet to attack Ceylon.

Admiral James Somerville, commander-in-chief of the British Eastern Fleet, wisely withdrew most of his ships from Ceylon on March 30. They sailed to a new secret anchorage in the Maldives, southwest of Ceylon.

Stranraer flying boats (below) on defensive patrols out of Dartmouth, N.S., at the outbreak of the war, was part of a small contingent left on guard in Ceylon.[Wikimedia]

With all Royal Navy warships and many fighter aircraft far from Ceylon, it left the responsibility for reconnaissance and visual early warning of a potential Japanese attack to a few RAF Catalinas and the four flying boats of 413 Squadron.

Admiral James Somerville (right), commander-in-chief of the British Eastern Fleet, relocated his ships to the Maldives as Japan advanced in the region. Birchall, who had piloted Supermarine Stranraer flying boats on defensive patrols out of Dartmouth, N.S

Onyette spotted “specks”on the southern horizon.

Before dawn on April 4, Catalina A rose into the air and made history. Under the command of Canadian Squadron Leader Leonard Birchall, among its eight crewmen was another Canadian, Warrant Officer Bart Onyette, the aircraft’s navigator.

Birchall, a 26-year-old native of St. Catharines, Ont., had graduated from Kingston’s Royal Military College in 1937 and then trained to be an RCAF pilot. He first served in Dartmouth, N.S., on anti-submarine patrols. By the time he was posted to 413 Squadron in 1942, he was an experienced pilot.

Members of 413 Squadron:

(left to right) squadron leaders J.C. Scott and Leonard Birchall and pilot officers A.M. Bell and

W.R. Meadows. [DND/PL-7404]

Birchall’s assigned patrol sector was the southernmost one, some 560 kilometres south and east of Koggala. After a dozen unproductive hours of scanning the vast waters stretching in all directions, Birchall was just about to return to base at 4 p.m. when Onyette spotted “specks” on the southern horizon. Birchall immediately headed toward them.

They were Japanese vessels.

Birchall flew directly toward the ships to count and identify them, fully realizing the closer he got, the less chance he had of escape. Slowly, Japan’s 1st Air Fleet came into view.

The fleet consisted of five aircraft carriers, plus battleships, cruisers and destroyers. The carriers had more than 300 modern combat aircraft embarked, including several first-rate Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters, which could outperform any Allied fighter in Asia at the time.

The enemy’s primary aim was to neutralize British naval and air resources in the Indian Ocean to secure Japan’s western flank. Birchall’s radio operator immediately began sending a coded transmission to Ceylon, containing details of the fleet.

But by then, with no clouds in which to hide, Birchall had been seen. As many as 12 Zeros swarmed in for the kill. Birchall later noted, “All we could do was to put the nose down and go full out, about 150 knots.”

When the operator was partway through his required third transmission, enemy cannon shells destroyed the radio, blew the operator’s leg off and set the aircraft on fire. The Catalina began to break up. It was too low for the crew to bail out, but Birchall managed to crash land safely on the water—just before the aircraft’s tail fell off.

Everyone but the operator evacuated the aircraft, although two crewmen were seriously wounded. Because they were unconscious, they were floating on the surface and unable to dive when Japanese fighters continued to strafe the Catalina and the airmen struggling in the water.

As the other survivors swam away from burning gasoline and the potential for exploding depth charges, the fighters strafed them and the Catalina, sinking it and killing the unconscious crewmen. Just as sharks began to approach the remaining six airmen, including the two Canadians, a Japanese destroyer finally fished them out of the water.

At Pembroke Dock in Pembrokeshire, Wales, in March 1942, members of 413 Squadron pose in front of the Catalina that Birchall (back row, seventh from left) piloted [Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame]

Birchall flew directly toward the ships to count and identify them.

Three of the survivors were badly wounded and Birchall himself had shrapnel in a leg. In response to questions from a Japanese officer, who “spoke perfect English,” Birchall identified himself as the senior officer. He was immediately beaten to the deck.

Every time he got up, he was beaten down again. The Japanese wanted to know if the Catalina’s crew had sent a report about their warships. But Birchall maintained only the wireless operator would know—and he had been killed.

In fact, the operator was one of the badly wounded airmen.

“He immediately became an air gunner,” Birchall later related, “and stayed that way for the entire war.” Just as he thought the Japanese were starting to believe him, they produced a radio intercept from Colombo asking Birchall’s Catalina to repeat its message. The crew were all beaten and locked up.

The message from Birchall’s aircraft had been garbled, but its meaning was clear: a Japanese attack was coming. When Somerville received this news, he ordered Colombo’s large harbour cleared of all shipping.

Unfortunately, the British had grossly underestimated the capabilities of Japanese aircraft—especially the range—and when 91 enemy bombers and 36 escort fighters appeared on the morning of April 5, RAF aircraft were still on the ground.

Forty-two fighters, mostly Hurricanes, scrambled to intercept them. The Japanese lost only seven aircraft to the RAF’s 19, but the aerial dogfights distracted the Japanese attackers from their primary mission and the port was only lightly damaged.

Although the Japanese had sunk some warships and merchant ships at a cost of 17 aircraft, they cancelled further major forays toward the west. The fleet sailed back to the Pacific.

In early 1942, the seaplane base in Ceylon was home to a number of Consolidated Catalina flying boats, including a few RAF planes and the four of 413 Squadron. [DND/PL-18358]

Birchall spent the next three and a half years as a prisoner of war in Japan and moved through four camps. Solitary confinement and daily beatings were routine; limited rations constituted a starvation diet. All prisoners, including sick ones, were forced to work.

Birchall’s natural leadership emerged, and he quickly earned the respect of other prisoners. When it came to food—the most essential commodity of all—he insisted that officers’ meals be displayed for all to see. If anyone thought an officer had been given more or better food, that individual had the right to exchange his ration for the officer’s.

Cigarettes were a valuable commodity, bringing momentary relief to the PoWs. Birchall gave up smoking and convinced the other officers to do the same and donate their cigarette rations to the men.

Birchall was almost tortured to death for attacking a guard who was beating a prisoner, but he did not stop looking after his men. He led them in a sit-down strike and refused to work until the guards agreed not to beat or otherwise mistreat the very sick. Birchall’s captors could not break his spirit and he was an inspiration to his comrades.

American troops freed Birchall after Japan surrendered. The diaries he kept while a prisoner and his testimony were used as evidence in war crimes trials of Japanese soldiers.

On Feb. 2, 1946, newly promoted Wing Commander Birchall was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire. His citation noted that as senior Allied officer in PoW camps, he “continually displayed the utmost concern for the welfare of his fellow prisoners…. Birchall continually endeavoured to improve the lot of his fellow prisoners…. The consistent gallantry and glowing devotion to his fellow prisoners of war that this officer displayed throughout his lengthy period of imprisonment are in keeping with the finest traditions of the [RCAF].”

Birchall also received the Distinguished Flying Cross for warning about the Japanese fleet. Prime Minister Winston Churchill later called Birchall’s exploit “one of the most important single contributions to victory” and the courageous pilot became known as the “Saviour of Ceylon.”

It was a term that Birchall never used.

Advertisement