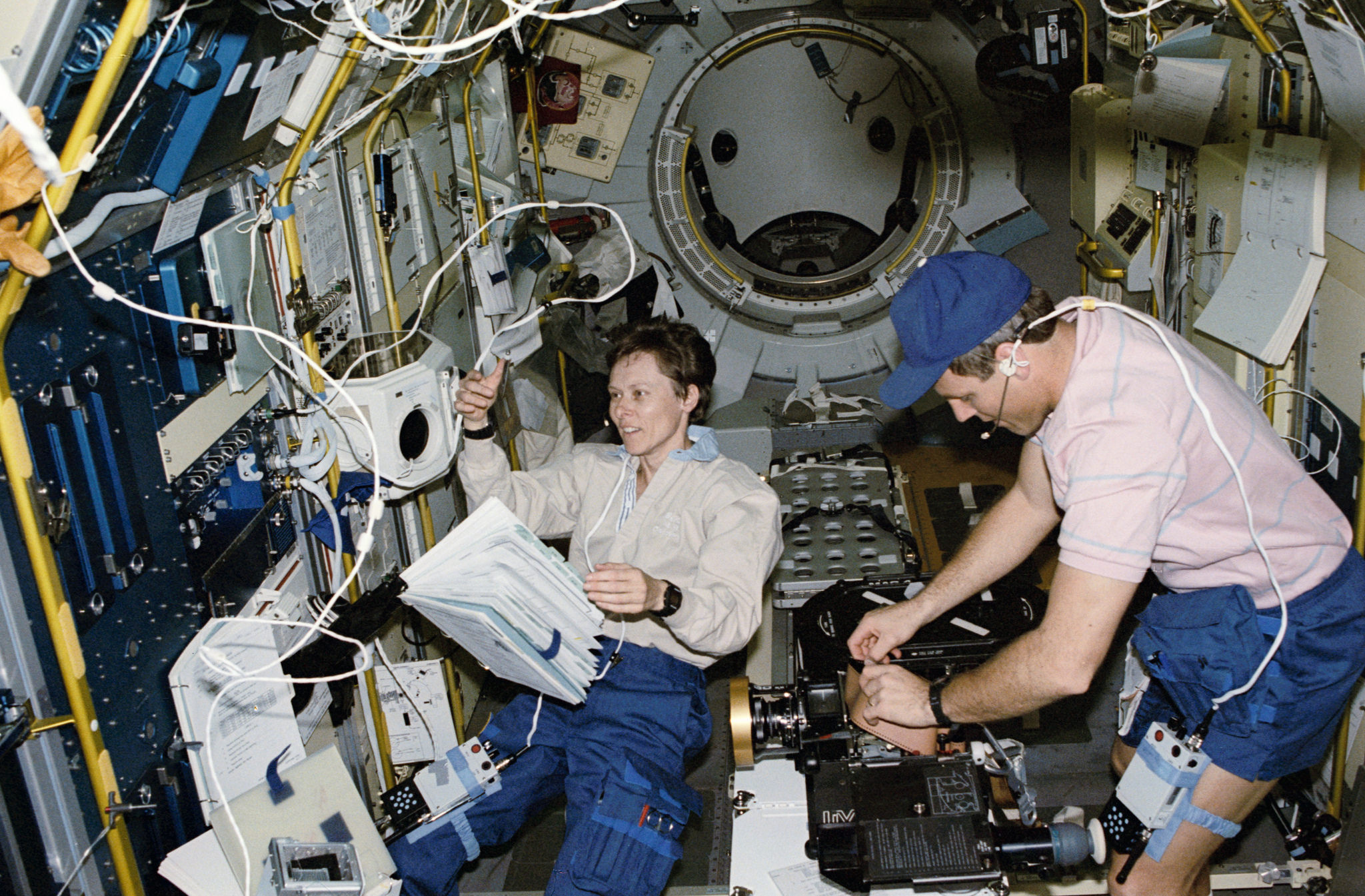

Canadian Roberta Bondar works with the International Microgravity Laboratory while astronaut Stephen Oswald, changes the film in the IMAX camera. [Flickr CC/NASA Johnson STS042-201-009]

While orbiting, she and the other astronauts conducted more than 40 experiments in the Spacelab on the first International Microgravity Laboratory mission, working 12-hour shifts to get all the work done in time.

They studied eye motion, the inner ear, energy expenditure changes in balance and the after-effects of space flight.

One of the objects of the research was discovering what working in space does to the body, and how to allow future astronauts to go on longer flights in space. It was known, for instance, that in weightless conditions astronauts’ spines can lengthen up to four centimetres, which caused back pain for some.

After they returned, astronauts underwent physical tests to note changes in their bodies from their 129 orbits around Earth. Bondar reported she hadn’t needed her glasses in space, likely due to the effect of weightlessness on fluids in the eye.

It took years to analyze the data collected. Bondar left the Canadian Space Agency in 1992 to lead, for a few years, NASA research teams that studied data from space flights to apply to medicine on Earth.

Roberta Bondar’s pioneering medical work has continued since becoming the first Canadian female astronaut to go to space on board the Space Shuttle Discovery in 1992. [NASA Archives]

Eye pressure changes in orbit. Spinal fluid doesn’t move as much. Some genes turn off in space. Some of the changes mimic the effects on the body of aging, and yet telomeres, structures in genes that slow chromosome deterioration (and thus aging), temporarily lengthen. There are small deteriorations in cognitive ability.

The body’s systems that help us tell up from down and where our limbs are in relation to one another, don’t function normally in weightlessness. One Apollo astronaut suddenly lost track of his arms and legs. “For all my mind could tell, my limbs were not there,” one said. A Gemini astronaut saw a watch floating before him, wondered where it had come from, then realized it was on his own wrist.

These effects can cause the vertigo, nausea and headaches known as space sickness. Research continues to counter such undesirable experiences. Bondar’s pioneering work has continued to this day. Rob Riddell, a flight surgeon with the Canadian Space Agency, is currently working on medical systems for deep space travellers.

Advertisement