As the Second World War wound down, Ottawa assumed wartime working women would return to homemaking—the women had other ideas

“Whether I marry or not, I want to have a job,” Alison Lindsey told a CBC Radio panel on “The Servicemen’s Forum” broadcast from HMCS Stadacona docked in Halifax on March 22, 1945. The war was winding down and the show’s discussion topic that day was the role of women after the war.

The number of women toiling in Canada’s wartime labour force peaked in the fall of 1944 at 1.2 million, nearly a third of Canadian workers. Ottawa’s Advisory Committee on Reconstruction reckoned the majority would revert to “the normal urge towards marriage, home, and family life” when the conflict ended. Leonard Marsh’s 1943 report for the committee backed the prospect, proclaiming women’s commitment was primarily to “homemaking and childbearing.”

But Lindsey’s philosophy echoed a growing refrain to the contrary. A 1945 Department of Labour survey revealed 72 per cent of women wanted to continue working after the war. They had experienced growth and independence—many for the first time—and now knew they had choices.

So, while generous veterans’ benefits applied equally to servicemen and servicewomen in establishing civilian careers, no such help came for those working women who had contributed to the war effort outside of the military. Though not facing the dangers of combat, female factory workers weren’t pushovers; in addition to the rigours of the job, most also had to manage their entire households as well.

Women did have some government help, however. In 1942, working wives’ and mothers’ annual salaries up to $660 were made tax-free and a federal-provincial agreement funded daycare and after-school supervision. That same year, such women were given the opportunity to apply for a 25 per cent supplement to the regular servicemen’s dependent’s allowance they received.

Despite the challenges, many women welcomed their new-found financial position, particularly in stereotypically male-held jobs. They were earning up to 75 per cent more than typical occupations held by females and, not surprisingly, they dreaded losing the income as peacetime approached.

72 per cent of women wanted to continue working after the war.

Maintaining the progress would be an uphill battle. The tax breaks designed to attract wives into the workforce during the war were eliminated in 1946, as was federal funding for daycare and after-school supervision. The prewar practice of excluding wives from civil service jobs was reinstated. And postwar, women were encouraged to take home assistants’ courses as opposed to training programs for jobs outside of the home.

The list of hurdles continued, but it spawned a time of vivid awakening and heated debates such as: “Is it right for married women to work? Would children suffer? Should men accept it?” The groundwork for permanent advances in women’s rights in the workplace was being irreversibly laid. Some recognition had already been building.

“You can tell your great-granddaughter some day that this was the time and the place it really started: the honest-to-goodness equality of Canadian women,” wrote Lotta Dempsey in a 1943 Maclean’s story. People were starting to think about equal pay legislation and other employment improvements that are now commonplace.

Despite its support for women’s domesticity, the Advisory Committee on Reconstruction recommended in 1944 that Ottawa pass legislation guaranteeing equal pay for equal work and that it introduce retraining programs for laid-off female workers. But the idea received a lukewarm response from MPs.

Clearly there was resistance to gender equality in the workplace. Seemingly radical changes in the daily lives of so many women during wartime had raised fears about the loss of morals and family stability. Conservative-minded Canadians thought women should return to domesticity, hinting that they were out spending their extra cash in bars and dance halls. Most Canadians accepted working mothers as an emergency measure—but only until the war was won.

Besides, the country was facing reintegration of some 600,000 soldiers, sailors and airmen into the economy after VE- and VJ-days.

So, working women were encouraged, pressured and cajoled in various ways to abandon the job market. Advertisements from appliance companies, for instance, showed them dreaming happily about their kitchens of the future once they were housewives again.

Conservative-minded Canadians thought working women should return to domesticity.

A Toronto mother leaves her children with a day nurse as she heads to work in a munitions factory in September 1943. [NFB/LAC/PA-116140]

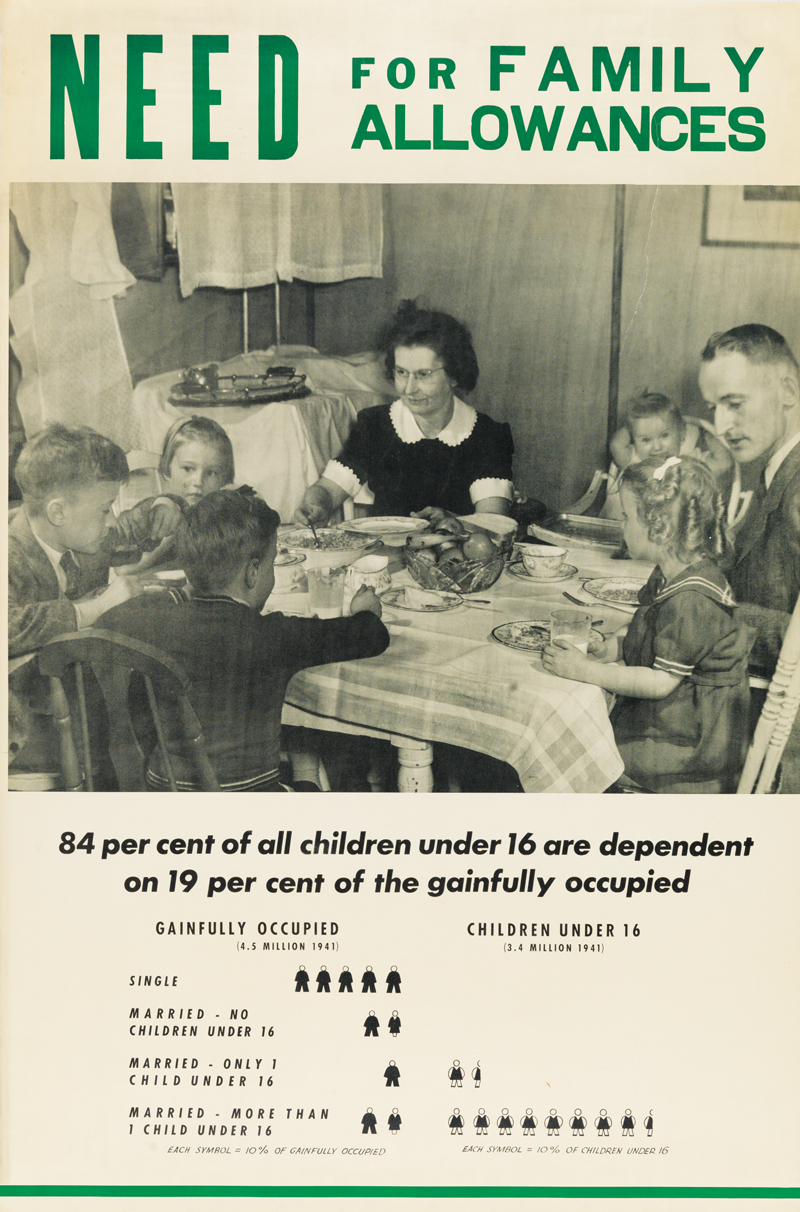

Even more federal initiatives were introduced to encourage domesticity. The 1944 Family Allowance program, monthly payments of up to $8 per child made payable directly to mothers, made it financially easier to have a family.

Veterans’ programs were generally designed to re-establish the man as family breadwinner.

The new Department of Veterans Affairs (DVA) provided several benefits to drive that home: pensions and cash payouts were higher than those after the First World War; previous employment, or a comparable job with a former employer, was guaranteed (which often terminated the employment of women in positions formerly held by men);

vocational retraining and university education were free; preference was given for civil service jobs; grants and subsidized loans were available to start a farm or business; and veterans collected an average of $700 in gratuity payments upon discharge.

Meanwhile, the opportunities for wartime working women continued to be bleak. In addition to the elimination of subsidies for working wives in 1946, unemployment insurance rules also worked against them. Barriers in the postwar employment market weren’t just policy. Canadian employers continued to stubbornly stereotype women’s careers: in 1950, nearly two-thirds worked in poorly paid clerical and retail jobs. Even those ex-servicewomen who took advantage of DVA benefits encountered barriers. About 2,000 entered university and about 8,000 chose vocational training programs. Yet the majority ended up in era-typical female fields such as hairdressing, office work and teaching.

A breakthrough came in 1951. Several union activists, backed by the National Council of Women of Canada and the Canadian Federation of Business and Professional Women, successfully lobbied for the creation of Ontario’s Female Employees Fair Remuneration Act. It caught on. Other provinces and territories followed suit with similar legislation.

Soon, several other federal laws kept the momentum: in 1953, the federal Fair Employment Practices Act applied gender equality to the civil service; in 1955, working wives were granted equal access to federal civil service jobs; in 1956, the Female Employees Equal Pay Act outlawed wage discrimination based on gender; and in 1957, the unemployment insurance program ended much of its discriminatory rules impacting women in the workforce.

The seeds of change planted in wartime sprouted and grew through the 1950s, gaining recognition and fresh opportunities for labour equality. It provided a solid foundation for further labour changes and feminist movements into the 1960s, ’70s and beyond.

Alison Lindsey was certainly prescient when she summed up her thoughts to that 1945 CBC Radio panel: “If women aren’t encouraged to work then society is worse off in the long run.”

Norway’s Frieda Dalen was the first woman to address the United Nations General Assembly, at its first session in London in January 1946. [United Nations/713009]

A long way

Postwar women’s movements have a history of expanding around the globe. Following the First World War, women wanted a role in shaping the peace, but were rebuffed. Undeterred, suffragettes from Allied countries gathered during the 1919 Paris Peace Conference for an Inter-Allied Women’s Conference and pleaded their cause. The result? A concession that was revolutionary at the time: all League of Nations positions had to be open to both genders on equal terms.

At the end of the Second World War, only eight female delegates attended the San Francisco Conference in 1945 that established the charter of the United Nations. Despite U.S. diplomats wanting only a generic commitment to include women’s rights, the charter solidly endorsed the “equal rights of men and women,” paving the way for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—now a worldwide pillar.

In its very first year, the UN established its Commission on the Status of Women as the principal global policy-making body dedicated exclusively to gender equality and the advancement of women. The fight continues. UN Secretary-General António Guterres stated recently that gender equality and empowering women and girls is the unfinished business of our time and the greatest human rights’ challenge in the world today.

Advertisement