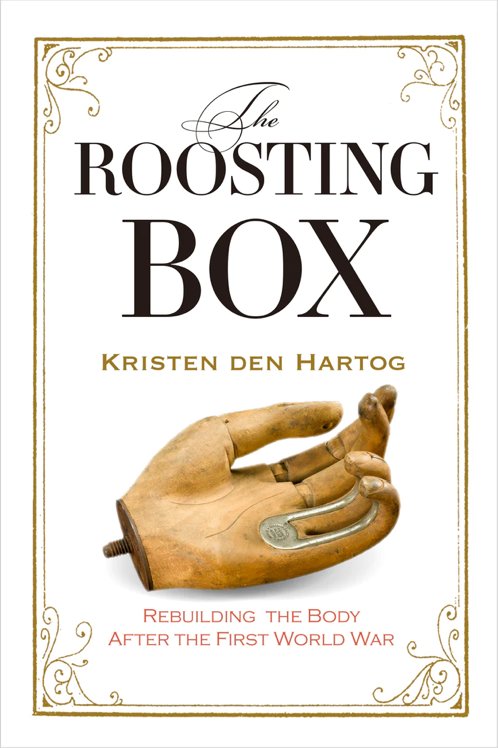

[Courtesy of Goose Lane Editions]

The roof ward was one of the marvels of the Christie Street Hospital, and came under the direction of a young doctor named Robert Inkerman Harris, who arrived at the facility with a gaggle of “war wrecks” wasting away from tuberculosis. Harris had suffered from tuberculosis as a child, and that old memory apparently fuelled his curiosity about the disease.

In the early 1900s, tuberculosis was the leading cause of death for Canadians between the ages of 15 and 45, spreading insidiously via the tiny droplets of coughs and sneezes. Because it was so common, the army did screen for TB during medical checkups of potential soldiers, but only by a physical examination and queries about family history of the disease, and not by x-ray of the lungs. X-rays, still rarely used at the beginning of the war, were really the best way to confirm the presence of tuberculosis, so the absence of these tests meant that many men entered service with a dormant infection that was at great risk of worsening in awful living conditions.

Soldiers were frequently exhausted and rundown; they lived in close quarters that were often cold and damp and impossible to keep clean. When the disease entered the secondary phase, it also spread to others more readily, and so tuberculosis brought down many men on all sides of the war.

The large numbers of soldiers who contracted the disease gave doctors the chance to expand on medical theories already underway. Absolute bed rest, usually for years, was a standard form of treatment. With Pott’s disease, the infection attacked the spine, depriving it of nutrients and gradually causing the bone to degrade. Early clues to the spread were back pain, night sweats, fever, and a general feeling of weakness and unease. For some patients, the illness caused permanent deformity and neurological issues; for others, the degradation was so severe that the vertebrae collapsed into a spinal cord injury.

At Christie Street, bone-grafting operations to try to reverse spinal deformities were often necessary, and plaster jackets or casts encasing the torso helped to ensure the body was resting in the right position as it healed. Harris employed these methods, but he was most intrigued by encouraging reports by Auguste Rollier, a doctor attempting to attack the disease with sunlight in the Swiss Alps.

Though Rollier apparently believed “only the kind of sunlight found on mountains would do the trick,” Harris was keen to try heliotherapy in Toronto. With the help of funds raised by the Parkdale Women’s Patriotic Association, “a little tin shanty” was erected on the hospital’s roof, and by spring of 1919, the men were in place, receiving the sun’s blessings.

Exposure happened gradually. Naked, with only a towel covering their genitals, the men received sunshine for 20-30 minutes on the first day, adding another 15 minutes each subsequent day. Once they were well tanned, the men could lie in the sun all day, being turned carefully so their backs and fronts got equal exposure, just like chickens roasting. Between each May and October, weather permitting, they were “sun worshippers,” spending upward of five hundred hours of the year this way, a number Harris thought surprisingly high, given that the hospital was situated in a smoky, industrial part of the city, right beside the railway tracks.

The nurses were nothing quite so delicate. They were more like the backbone of the hospital.

In fact, sometimes the sun was too intense, and the heat, on a building with a gravel roof, proved excessive. Little canopies were devised to keep a patient’s head shaded, when necessary, and “smoked glasses” cut the glare that could otherwise cause conjunctivitis. The patients were delivered cool drinks, and electric fans sent a gentle, delicious breeze over their basking limbs and torsos. These details—shades, refreshments and breezy sunshine—form a picture of tropical paradise when compared with chewed-up battlefields.

Photographs suggest that other patients visited the rooftop, too, just because it was a pleasant place to be, and no doubt it was cooler on hot summer nights as well. In such an environment, the men’s spirits rose and their skin bronzed. Their bodies filled out, too, on a plentiful diet rich in milk and eggs. So encouraging were the results that new patients were regularly added to the “rooftop garden,” as the men called it, tended there by the nurses nicknamed “roses.”

The nurses were nothing quite so delicate, of course. They were more like the backbone of the hospital. Women had to be 21 before they could begin their nurses’ training, which took three years and an abundance of courage and stamina. Mabel Lucas, who worked on the roof ward at Christie Street, first applied to the school at Toronto Western Hospital in 1908; she weighed 94 pounds and was told to come back and apply again when she weighed 100.

Finally accepted, she lived in a tent on the hospital grounds, and spent her probationary period making beds and emptying bedpans and learning about anatomy, surgery, and pathology. There were lectures on diet, and training sessions from masseuses, and there was ample opportunity to reach a new level of comfort with the human body, for some patients were horribly filthy, or riddled with disease. Emotional fortitude was built into the curriculum: you had to learn to let people go.

Mabel’s first such ache was for a frail old lady no one ever visited. “I used to look after her and sort of give her a little extra attention whenever I could…. I knew she was very ill and they said there was no chance for her.” But when the woman died, Mabel was called on to assist as the old woman’s body was tended to. She stood “crying and crying” as the staff washed the woman, packed her rectum, put bandages under her chin, closed her eyes and laid pennies on her eyelids.

“It was the first death I had ever seen. [The senior nurse] said to me, ‘I wonder how much use you’re going to be around here if that’s the way you act.’” She couldn’t have imagined, then, what she’d be able to endure later, at war: tent life, again, but in Salonika, with scorpions and spiders; the rotting-meat smell of gangrene; buckets spilling over with severed arms and legs; letters that needed careful writing to mothers and fathers. Once, during a bombing raid, rather than finding shelter, she stayed in place, guarding her unconscious patient. “He was dying,” she said, “[and] a nurse had to be there.”

Advertisement